Art

| The following article on Peter Schumann and the 'Bread

and Puppet Theater' was copied from

Z magazine |

|

The New Wave of Activist Art

By Mimi Yahn

In 1962 Peter Schumann, a German-born sculptor, dancer,

and musician living in New York City, opened the doors to the Bread &

Puppet Theater, a low-budget, politically progressive theater arts project

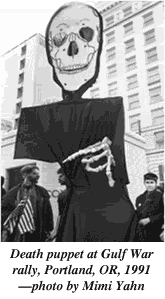

featuring gigantic, stunningly emotive puppets. These stark ten-to-fifteen-foot

puppets were used at marches and rallies to personify the horrors of war.

They were also performed in storefronts, churches, and on the streets to

tell people about the inhumanity of war, racism, poverty, and a range of

other injustices.

Schumann’s Bread & Puppet Theater was more than just

big puppets and “educating the masses” through dramatic storytelling, it

was a new kind of theater, different from the other people’s political

theater of the time, Ronnie Davis’s San Francisco Mime Troupe. It was Davis

who first called it guerrilla theater, a term that later changed to street

theater as it evolved into the broader concept of incorporating a wide

range of artistic disciplines into the concept of using art to convey political

ideas.

Probably the most revolutionary aspect of the Bread &

Puppet Theater was its dedication to public accessibility, its fundamental

belief that art belonged to the people. It was this concept that planted

the seeds for a revolutionary new wave of activist art.

Art in the service of social change is certainly nothing

new. Throughout history political art has generally been created by professional

artists who were inspired by events to get involved through their work

or to lend their art to the cause. Two notable periods of activist art

in the past century were the 1930s and the Civil Rights, anti-war, and

free speech movements of the 1950s and 1960s.

The 1930s produced an exceptional wave of political graphic

art, inspired in part by Soviet Realism, in part by the gritty Ashcan School,

and in part by the German Bauhaus movement, which believed that art should

be mass-marketed. At the same time, the politics of the times—the Depression,

the disillusionment with war, the growing socialist movements around the

world, and the homegrown uprisings like the Bonus Army March and the Southern

Tenant Farmers’ Union strike—inspired a generation to use their art to

spread radical ideas. From novels to newspaper exposés, from Broadway

theater to Hollywood movies, progressive writers created a body of work

that has endured and even become a staple of American literature.

Our government actually helped broaden this process by

hiring artists by the thousands through the Works Progress Administration

(WPA). Along with the writers, the actors, playwrights, and artists, the

WPA hired photographers to document the lives of the poor, thereby giving

birth to a new, activist photojournalism.

But all of this innovative, dynamic activist art was

created by professionals—by those who did art for art’s sake as a living

and as a way of life. The activist art of the 1930s was not, for the most

part, created by amateurs.

The political movements of the 1950s and 1960s galvanized

people in all the arts—from painters and playwrights to dancers and musicians,

from sculptors and filmmakers to poets and photographers. But, once again,

the world of activist art adhered to the notion that though art should

certainly be created for the people, it was not created by the people.

In 1962 the Bread & Puppet Theater was not so much

a revolution in who creates the art, but a revolution in the purpose, aesthetic,

and accessibility of art. The dominant paradigm that guerrilla/street theater

sought to overturn was the notion that art was only for a select few—professional

“artists” and those who could afford the luxury of appreciating it. As

the Bread & Puppet’s “cheap art manifesto” proclaimed, “Art is food.

You can’t eat it but it feeds you. Art has to be cheap and available to

everybody.”

Because of this notion that art belongs to the people,

Schumann revived traditions of folk arts that were either dead or dying:

pageantry, puppetry, and broad-stroke allegorical storytelling. As a result,

his new/old theater style wasn’t meant to be polished, it wasn’t meant

to conform to a rigid aesthetic. Guerrilla/street theater was as grassroots,

down and dirty, funky, and undisciplined as any art could be. It showed

the world that art was relevant to people’s lives.

Meanwhile, the 1960s devolved into the 1970s, the decade

that ground up art and reprocessed it for mass commercial consumption.

A key component of that commercialization was the notion that art could

only be produced by professional, paid artists. Even singing was handed

over to the “professionals” and their commercial sponsors.

Through all that commercialization and reconstruction

of elitist doctrine, guerrilla/street theater continued to spread in urban

neighborhood community groups, in rural caravan-type AIDS awareness campaigns,

as tools in teaching women how to escape domestic violence or showing workers

how to organize and win. Like the traveling theater and circus troupes

of the past, these grassroots, amateur street theater productions have

become a staple of community organizing, education campaigns, and public

health initiatives throughout the world. The participants in this revolution

have overcome the fear of art, they’ve discovered that art is fluid, art

is alive, art is meant to cross-breed, hybridize, and mutate into greater

art.

The revolution of guerrilla/street theater has influenced

progressive movements across the globe and has resulted in a democratization

of art that is exciting and potentially liberating. The list of individuals,

groups and campaigns participating in the new wave of activist art is growing

nearly as long as the list of activists themselves. I’m elated to see huge

numbers of satirical, witty, and truly comic posters and billboards. Admittedly,

our current Administration pretty much writes its own material—however,

a sense of humor is essential to survival and a movement of people who

come up with phrases like “Who Would Jesus Bomb?” and “A Village In Texas

is Missing Their Idiot” is not only surviving, but is also thriving and

using critical thinking skills.

Obviously, a good many of those creating activist art

are, in fact, artists, but this new wave of activist art has allowed artists

to thrive and create far beyond the confines of the old, rigid paradigm

and far beyond the mind-numbing commerciality of today’s marketplace. One

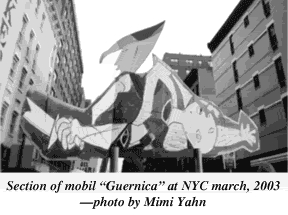

example of how activism inspired art was the mobile work created by a group

of artists for the February 2003 peace demonstration in New York City.

It consisted of a giant replica of Picasso’s stunning anti-war mural, “Guernica,”

which the artists recreated as separate sections to be held up like signs.

Periodically on the march, they’d come together to hold the sections in

their original form, thereby turning a work of art with a powerful anti-war

message into an even more powerful performance piece.

Such collaborative “street theater” pieces are becoming

more and more common, particularly among non-artists. The massive procession

of coffins at the 2004 Democratic Convention in New York; the December

2002 Oakland, California display of coffins mourning Iraqi children; the

elaborate, gigantic peace doves with moving wings; the individuals who

made activist art with duct tape on their clothes and faces; the sidewalk

theater pieces of Lady Liberty chained and gagged by Uncle Sam or Uncle

Sam trying to wash the blood from the flag—these are just a tiny fraction

of the activist art being created and displayed by non-artists in recent

years.

The new wave of activist art doesn’t just include visual

and street theater art. Over the last decade, thanks in great part to the

anarchist bloc, music and dance have become an integral part of every demonstration.

The raucous drumming of the anarchists’ Bucket Brigades provide communal,

danceable music while the Radical Cheerleaders lead the crowd in dance

steps and subversive chants.

Many activists who also play all kinds of instrument

have taken to bringing them to demonstrations because, invariably, they’ll

find other musicians and form impromptu bands or hook up with an existing

band. At the larger demonstrations in DC or New York, if you get tired

of marching alongside the Bucket Brigade, just hang back till the marching

jazz band comes along or wait a while longer for the samba players and

in between you’ll likely find a group of Raging Grannies leading the crowd

in the “Granny Iko-Iko” or “This Land Is Your Land.”

The Raging Grannies are an excellent example of how the

democratization of art has brought about a transformation on both the political

and the personal levels. Though the group was started nearly 20 years ago

in Canada by a group of women who used their age and gender to get past

guards into a military installation and begin singing satirical songs from

the illegal side of the fence, it wasn’t until five years ago that momentum

really began building and Raging Granny “chapters” popped up all over the

map. Though the majority of them had no past experience as singers or songwriters,

the combining of art with activism has emboldened them to get up and sing

in front of strangers and sit down in front of recruiting stations.

In addition to the proliferation of theatrical die-ins,

spy-ins, and other political actions, the spirit of street theater has

inspired a number of activists to form groups utilizing a single, bold

visual statement to symbolize their message.

In 1988 a group of Palestinian and Israeli women began

a weekly vigil to protest the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza

Strip. Dressing only in black and mostly remaining silent, they called

themselves Women In Black and held black placards in the shape of a hand

with words written in white across the palm: “Stop” or “Stop the Occupation.”

The women endured daily harassment and insults—they were called “whores”

and “traitors”—but they refused to leave. As word of this vigil spread,

other women around the world began their own Women in Black vigils in solidarity.

The Women in Black vigil in Berkeley, California has been held without

fail every week since 1988.

In 1991 a group of feminists began a Women in Black vigil

in Belgrade’s Republic Square to protest the nationalist aggression fueling

the ethnic wars that were tearing Yugoslavia apart. They were also protesting

violence against women and male violence in general. Like their sisters

in Israel, they endured verbal as well as physical harassment, but refused

to stop their silent vigil.

The Serbian Women in Black extended the purpose of the

group to stand in opposition to war and aggression everywhere and in opposition

to violence perpetrated by men against women. Today, there are Women in

Black chapters in dozens of countries, many of them in active war zones.

While some continue the silent vigils, others conduct marches through busy

areas, beating drums and using masks and giant puppets.

In 2002 another group of women seized on the use of color

as a piece of memorable street theater: CODEPINK. Led by long-time activists

Medea Benjamin, Diane Wilson, and Starhawk, the selection of the color

pink was a deliberate snub at the Bush regime’s heavy-handed fearmongering

campaign. It’s the antidote to the color-coded terror alert system and

it’s an image that’s intentionally satirical, celebratory, and subversive.

Like all great street theater, CODEPINK actions are colorful,

outrageous, and splashy, and humor is an integral part of their identity.

Their recurring motif is the double entendre image of the pink slip—as

clothing, banners, and slogans—while one of their standard slogans proclaims,

“CODEPINK Women Say Pull Out.” And best of all, it’s always easy to find

the CODEPINK bloc at any demonstration.

The Radical Cheerleaders also use clothing as part of

their street theater. Along with the tutus and batons juxtaposed with combat

boots and jeans, the Radical Cheerleaders mix dance routines and rhythmic

cheers in a theatrical, satiric subversion of women’s traditional role

as passive cheerleader. Like the Raging Grannies, the Bucket Brigades,

the Women in Black, CODEPINK, the satiric Billionaires for Bush, and all

the other individuals coming together to make art while making peace, they

don’t have official chapters or formal structures. They come together as

autonomous groups to create, rehearse, and create some more, then come

together with the rest of the world to display their activist art.

Perhaps one of the most astonishing activist art phenomenons

began in 2002 during the days and months of worldwide protest against Bush’s

pending pre-emptive war, when a group of women calling themselves Baring

Witness stripped naked and formed the word “Peace” with their bodies on

a field in Point Reyes, California. Something about that action took hold

and since then, tens of thousands of other people have participated in

similar actions across the globe, some nude, some clothed. In Paris, people

formed a nude peace sign in front of the Eiffel Tower.

In New Orleans activists stripped atop the Mississippi

River levee and formed the words, “Buck Fush” while in New York City’s

Central Park, people lay down in the snow before the Bethesda Fountain

to spell the words “No Bush.” In Antarctica at the McMurdo Station the

full complement of international scientists formed a peace sign with their

clothed bodies and when the U.S. government warned them against making

political statements, they went back outside, stripped off their clothes

and held up a white banner with an exclamation mark at the end of the censored

political statement.

Since that year, there’ve been hundreds, maybe thousands,

of local and global actions involving art and politics, joining artists

and non-artists in creating activist art. There was the night of the global

readings of the Greek anti-war play, Aristophanes’s Lysistrata. There was

the Pax Musicata that joined musicians around the world to come together

and play music for peace for one day and night. There’ve been countless

Poets for Peace readings and poetry has become as standard at rallies as

music. Meanwhile, Eve Ensler’s Vagina Monologues continues to be performed

every year on Valentine’s Day in theaters, college campuses, coffee shops,

and countless other venues across the country.

Locally, artists and non-artists join together in collaborative

activist art events, like Pittsburgh’s PeaceBurgh project where families

came together at a community center to drum, sing, and decorate large peace

dove cut-outs. Pittsburgh university students also organized a Dance-A-Thon

to publicize the University of Pittsburgh’s failure to adopt an anti-sweatshop

policy. As they danced on a public walkway, they handed out leaflets to

passersby and engaged them in dance and conversation. Last year’s 100th

anniversary of the radical union, the Industrial Workers of the World,

inspired musical events, poetry readings, and art exhibits by workers in

cities across the country that hosted the traveling Wobbly Art exhibit.

This year’s May Day—the workers’ holiday reinvigorated by immigrants—inspired

activist art celebrations from San Francisco to New York. In Pittsburgh

the event included poetry, a stand-up comedy routine, and the first workers’

skit to be performed in decades.

Technology has also played a huge role in spreading the

idea that art is created by the people for the people. It has turned the

Internet into a massive people’s artspace, a place to post your own political

photos, graphics, videos, articles, music, poems, etc. for all the world

to see and share. The most extensive and well-known of these sites is the

IndyMedia network that accepts articles, photos, videos, and audio recordings

from progressives around the globe.

This new wave of activist art is more than a revolution

in art and how we relate to art, it’s a revolution in how we, as activists

and human beings, respond to the dominant paradigm that teaches us to be

passive viewers of art rather than active creators of art. The more democratized

art becomes, the more people understand that art is for us to create, to

nourish our humanity, the closer we come to understanding and achieving

democracy in our everyday and national existence.

Mimi Yahn is a writer, long-time activist and a singer/songwriter

living in Western Pennsylvania. She is the former editor/publisher of the

Feminist Broadcast Quarterly of Oregon. Yahn is also the musical director

for the Pittsburgh Raging Grannies and publisher of the online political

satire ‘zine, the Swiftian Report.

(Source: Z magazine online edition )

© by Z magazin and/or Mimi Yahn

Presented here only as a back copy added to the LINK

TO THE ORIGINAL Z-MAG ARTICLE, this is not an integral part of this

issue of Art in Society |