| American Geopolitical Strategy in Europe Since 1990

The "End of the Cold War" and German Unification /

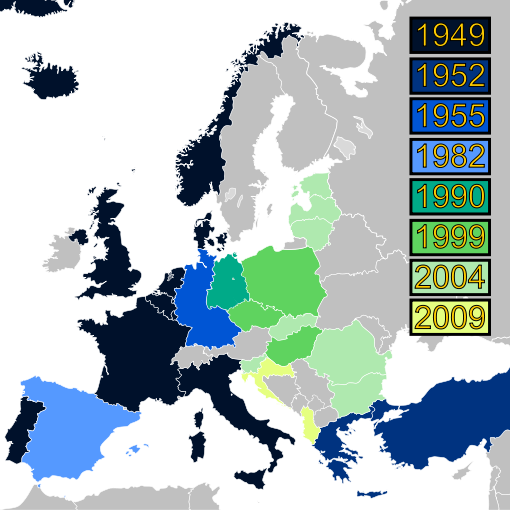

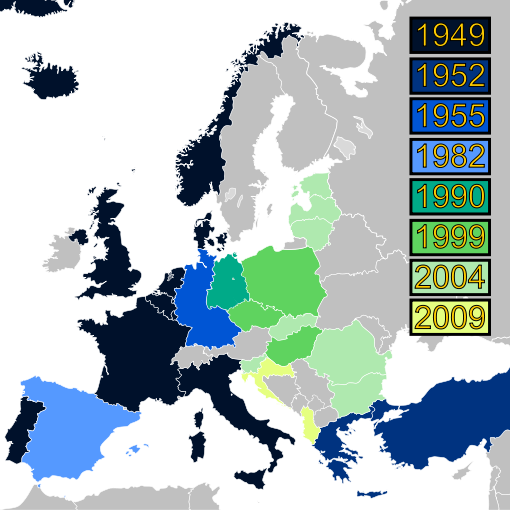

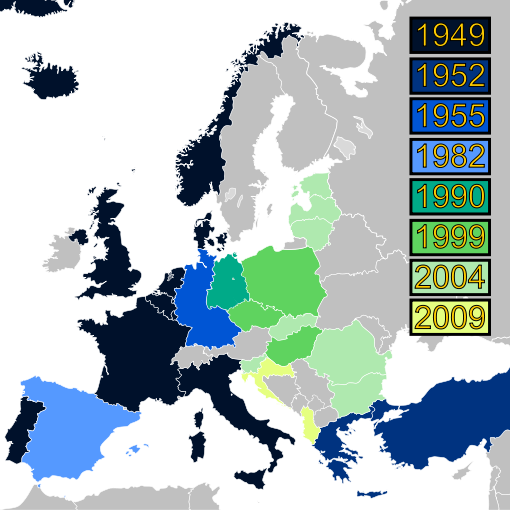

NATO in Europe: Expansion in 1990, 1999, 2004, 2009

- and what's next?

Map of a part of Europe, showing the addition of new members of

NATO since 1952.

Preface

It is obvious that at present, in the spring of 2014,

we are facing a crisis of major proportions in Europe that affects "world

politics" - in other words, the political and economic situation of humanity.

For some it is a crisis "in Ukraine" (a country that a majority of U.S.

citizens cannot locate on a map of the world), for others, a crisis unleashed

by what they term Russian occupation of the Crimean peninsula (an occupation

that in fact, occurred but that has a complex background which requires

to be considered); for still others, it is a conflict between the U.S.

and Russia that has been noticeable for quite a few years already, and

that has come to our attention with great force, as events in Ukraine unfolded

this year,

It cannot be overlooked that all of these interpretations

are, to some extent, justified. As human beings, as citizens rooted in

what amounts to a specific socio-cultural history (and often tied to particular

interests), people tend to view historical developments - and the social

reality they face in a given moment - from specific perspectives. Many

factors influence our perception, and it can turn our that this perception

is too narrowly focused, or too generalizing. Oral history, family history

but also school books, the media, the prevailing type of discourse in our

specific society come into play. It is perhaps a fiction that a sober,

objective, impartial analysis is possible in a world where the material

interests of different "powers" and different classes are divergent, if

not antagonistic, and where ideological coloring of discourses is often

unnoticed by speakers (and the listeners) but nonetheless all the more

present.

If different perspectives of the crisis of 2014 are possible,

this attempt to situate it in a bigger, more profound, ongoing development

that deserves to be called a "long, ongoing, antagonistic crisis" (or conflict)

clearly presents one of several possible view. Those who live in the Baltic

countries, or in Poland (countries that were subjected by Czarist

Russia, and later on experienced the Soviet reality in a painful way while

also adding to the pain of [Soviet] Russian citizens) obviously have

their own story to tell and tend to have their own perspective.

Outsiders may well understand the trauma that resulted

and the specific "security interests" (in the face of a big Eastern neighbor)

that have let them favor "integration" into NATO and the European Union,

while resenting perhaps even the thought of Russian membership in either

NATO or the EU.

But historical experience has not only produced a trauma;

it has also produced resentment. And as happens so often (for who,

in which country, is exempt from it? perhaps very few, a minority, in most

cases, in our present world), it has resulted in a selective memory

that privileges the retelling of one's own suffering while largely ignoring

the suffering afflicted on others. Or how would it be otherwise possible

to feel no shame, in countries like Latvia, in view of the staunch participation

of Lativian SS-troops since 1941, side by side with the Nazi-aggressor,

in genocide against Jews and Slaves and in the fight against the alliance

of Britain, the U.S. and the Soviet Union? How would it be otherwise possible

in Poland to forget that country's expansionist eastward drive, its intervention

in the Russian civil war, its war against a weak and defensive Soviet

Russian Republic, in the years after the end of World War I? Strife between

neighbors rarely has no "pre-history" and it seems that in most cases,

it would rarely allow us to put the blame squarely on one side.

This said, it seems fair to point out that of course feelings

of insecurity in the Baltics and Poland have to be respected, and the same

is true of the wish (if it exists) of the majority of the people in these

countries to belong to a neo-liberal politico-economic union directed by

a Commission that is endowed with exceptional prerogatives (based on treaties,

not popular will) and a parliament with no right to pass laws on its own

accord. But so have the feelings of concern about an increasingly insecure

global situation, that exist in many countries of the world. They are based

on an analysis of NATO expansion since 1989 that implies a different perspective,

by putting this expansion into the context of US-Russian relations and

privileging a view of persisting tension between the US, as the only remaining

superpower since about 1990, and Russia.

For those who do not desire an unipolar global constellation,

the further strenghtening of the remaining superpower and the additional

weakening of Russia must be a cause of concern. The Soviet reality has

not only been painted in dark colors by Western Cold War rhetoric; even

those who shared the ideals underlying the October Revolution question

a lot of what went on in the Soviet Union and within its orbit. But the

remaining superpower has a record that is not as favorable as it has been

painted, at least by most Western media most of the time. A Pax Americana

might well be seen as the era of dominance of a country where an oligarchic,

tiny elite quite ruthlessly pursues its particular interests. This does

have repercussions, and not necessarily favorable ones, all around the

world.

As far as Russia is concerned, it's not only the Western

media (whose owners and editors - and with them, quite often, many of the

employed journalists - make us stubbornly ignore the inadequacy

and endangered reality of democracy in the U.S. and the EU) who point out

the inadequacy of formal democracy in present-day Capitalist Russia. In

Russia, there is a lot of discontent, too, just as in Spain, Portugal,

Greece, Turkey, and a few other European countries. But 70 or 80 per cent

of the adult Russian population, according to an article of the New York

Times, favor the present Russian government's stance in the case of the

present crisis over Crimea and its stance regarding the present Ukrainian

leaders in Kiev. Even Gorbachev sees the reintegration of the Crimea into

Russia as an understandable and historically justified act, and like the

Russian president, he would not like to see a NATO presence in Ukraine

and the Ukraine's informal or formal integration into that military alliance.

Like various observers in the West, Russian leaders see

the NATO presence in the Baltic countries, its moves to integrate the Ukraine

and Georgia, and the determination to establish a "missile defense shield"

as a policy to establish a US nuclear first-strike capability. If achieved,

it would subject future Russian governments to the diktat of the

U.S. elites. And by eliminating the voice of Russia as a (potentially)

independent voice, it would make a similar move against China even more

likely, warding off every attempt of countries in the South to create a

more evenly balanced, fairer, more democratic multi-polar constellation.

Pessimists may see in the present crisis a symptom, comparable

to the crises that foreshadowed World War I. So-called realists will try

to paint such pessimism as unwarranted; they tell us that "deterrence"

has "worked" quite well, that no nuclear power will risk a suicidal big

war; and they forget how close the world was repeatedly, after 1945, to

an accidentally or consciously unleashed World War. The Cuban Crisis should

not be forgotten. If the stationing of missiles on Cuba had proceeded,

everything would have been possible. Likewise, we must asks at least the

question whether a cornered Russian leadership, faced with the on-going

attempt to move nuclear attack weapons (bombers, warships, missiles) so

close to the Russian front door, might not, in desparation, opt for a "first

strike" before the other side does it? A scary question, and human reason

should keep both sides from considering such steps. But which war was unleashed

in this century that was not driven, in hindsight, by an absurd and criminal

rationale?

Promised Detente, Promises of Cooperation, and the Seeming

End of the Cold War

In the 1980s, the crisis over the stationing of median-range

missiles in Germany and Italy and the immense economic and human cost of

the arms race unleashed by the Reagan administration, but also the promises

inscibed in the tactics of Ostpolitik, pursued by West German governments

(Bahr, Genscher, Brandt, finally even Genscher and Kohl) led the Soviet

leadership to rethink certain positions.(1) The unwinnable war waged in

Afghanistan against US-supported insurgents contributed to this process.

Internally, a strategy to broaden popular support by increasing the standard

of living had brought results in the 70s and early 80s but the arms race

had increasingly made the strategy ineffective and thus internal dissatisfaction

increased. (The negative social consequences of the arms race in the U.S.

should not be ignored here, they included the deterioration of public infrastructure

and a vast budget deficit.) The rise of Gorbachev and the increasingly

socioal-democratic positions that replaced the "old thinking" among parts

of the classe politique in the Soviet Union prefigured the diplomatic rapprochement

that found expression in the promise to withdraw from Afghanistan and also

in the ralks that lead up to the so-called Two Plus Four Treaty.

The Pre-history of the Two Plus Four Talks

July 1986

"In July 1986 six regiments, which consisted [of] up

to 15,000 troops, were withdrawn from Afghanistan. The aim of this early

withdrawal was, according to Gorbachev, to show the world that the Soviet

leadership was serious about leaving Afghanistan. [...]The Soviets told

the United States Government that they were planning to withdraw, but the

United States Government didn't believe it. When Gorbachev met with Ronald

Reagan during his visit the United States, Reagan called, bizarrely, for

the dissolution of the Afghan army [...]"(2)

April 1988

On 14 April 1988 the Afghan and Pakistani governments

signed the Geneva Accords, and the Soviet Union and the United States signed

as guarantors; the treaty specifically stated that the Soviet military

had to withdraw from Afghanistan by 15 February 1989.

January, 1990

“Gorbachev's worries[regarding the possible consequences

of German unification][...] were eased by promises from the American, French

and German government that NATO would expand no further to the east. Perhaps

he was lulled by the fact that Time magazine chose him as the "Man of

the Decade" for the first January issue, 1990, and in an accompanying

essay editor-at-large

Strobe Talcott mused that "[i]t

is about time to think seriously about eventually retiring [i.e. dissolving]

the North Atlantic Treaty Organization." [...] (3)

Peter E. Quint mentions “a crucial early suggestion

of German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher, advanced in January

1990, that eastern Germany [would] forever remain free of NATO troops.

The purpose of Genscher's proposal was to help make German membership

in NATO palatable to the Soviet Union by assuring that after unification

NATO forces would not move closer to the borders of the Soviet Union

than they had been before unification.”(4)

August, 1990: The

United States launched Operation Desert Storm. On August 7, 1990, the first

U.S. troops arrived in Saudi Arabia.

The Two Plus Four Talks

September 12, 1990 The Two Plus Four Treaty between

the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), the German Democratic Republic (GDR),

and the Four Powers that occupied Germany (US, UK, F and USSR)

"Two Plus Four" Treaty Signed in Moscow

The "Treaty on the Final Settlement With Respect to Germany"

more commonly known as the "Two Plus Four Treaty" was the final peace treaty

negotiated between the Federal Republic of Germany, the German Democratic

Republic, and the Four Powers that occupied Germany at the end of World

War II in Europe - France, the United Kingdom, the United States and the

Soviet Union.The treaty was signed in Moscow on September 12, 1990. The

treaty paved the way for the German re-unification, which took place on

October 3. Under the terms of the treaty, the Four Powers renounced all

rights they formerly held in Germany and re-united Germany became fully

sovereign again on March 15, 1991. The Soviet Union agreed to remove all

troops from Germany by the end of 1994. Germany agreed to limit its combined

armed forces to no more than 370,000 personnel, no more than 345,000 of

whom were to be in the army and air force. Germany also agreed it would

never acquire nuclear weapons. [...]

.

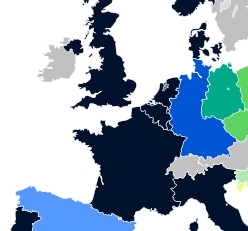

The countries shown in dark blue are "core" NATO countries.

The countries depicted in green were "communist countries" in 1990.

West Germany (the FRG) is depicted in bright blue; East Germany (the GDR)

in dark green. East Berlin was the capital of the GDR; West Berlin had

a special status. The promise given at the time to Mr. Gorbachev

and Mr. Shevardnadze was that NATO troops other than a limited number of

West German NATO units would not be stationed East of West Germany's borders. |

The question whether the Two Plus Four Treaty and other agreements

between Western governments and the Soviet Union precluded eastwards expansion

of NATO has given rise to controversy.

Quite obviously, Soviet leaders at the time understood the treaty (and

other assurances they were given) as a clear commitment of the West that

NATO would not expand.

Western diplomats have later said that no precise assurances were given.

The treaty and the assurances could be read in the way the Russians read

them, but they included enough gaps unnoticed by the Russians to allow

eastward expansion later on, after the unification of Germany (and Soviet

approval of unified Germany's membership in NATO) had been achieved. There

exists, however, a general consensus that the West, in 1990, wanted the

Soviet leaders to believe that a promise precluding NATO's further expansion

had been made. |

September 14, 1990 The German - Soviet Russian

"Treaty on Good Neighborliness. Partnership and Cooperation"

On September 14, 1990, Serge Schmemann wrote in the New York Times that

“[t]he Soviet Union and West Germany today initialed a broad ''treaty

on good-neighborliness, partnership and cooperation'' setting a framework

for relations between Moscow and a united Germany.Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich

Genscher of West Germany and Foreign Minister Eduard A. Shevardnadze of

the Soviet Union, who initialed the document, hailed it as something of

a historic breakthrough. [...] [T]he treaty [...] consisted largely of

pledges of peace and cooperation. [...] [T]he document had been part of

the package sought by the Soviet Union in exchange for its agreement to

German unity. [...] [It amounted to a] broad statement on the shape

of future relations. [...] [A] united Germany was prepared to put its peaceful

intentions on paper. […] The preamble declared that both sides were ''resolved

to continue the good traditions of their centuries-old history,'' and spoke

of ''historic challenges on the threshold to the third millennium. […]

The document included statements banning aggression against each other

and calling for annual summit meetings, consultation in times of crisis

and expanded trade, travel and scientific cooperation. Though it had no

detailed projects, officials said separate treaties detailing economic

relations, including German financial aid for the Soviet Union and incentives

for trade and investment, were under negotiation. ''The treaty leads

both our countries into the 21st century marked by responsibility, trust

and cooperation,'' Mr. Genscher said. Mr. Shevardnadze called the treaty

a ''historic document in spirit and content,'' adding: ''Now we can rightly

say that the postwar era has ended. We are satisfied that the Federal Republic

and we again appear as partners. This is a great thing.''

Serge Schmemann, “Moscow and Bonn in a 'Good Neighbor' Pact,” in: The

New York Times, September 14, 1990 http://www.nytimes.com/1990/09/14/world/moscow-and-bonn-in-a-good-neighbor-pact.html.)

September 28, 1990

Meeting of the Representatives of the Baltic States, [in] Riga, Republic

of Latvia September 28, 1990 To the members of the United States Senate:

On September 12, 1990, the Two-Plus-Four Treaty was signed in Moscow

as a result of negotiations on Germany’s reunification. On September 13,

1990, a bilateral Treaty on "Goodneighborliness, partnership and co-operation"

was initiated in Moscow by the Soviet Union and the Federal Republic of

Germany. Proceeding from those documents and taking into account the results

of the Helsinki 90 Summit between the United States and the Soviet Union,

the Baltic States welcome the reunification of Germany.

However, Article 2 of the Soviet-German Treaty of September 13, 1990,

contains principles that may be considered as acknowledging the Conquest

of the Baltic States by the Soviet Union towards the end of World War II.

The Baltic States draw attention to the dangers inherent in the

unconditional ratification of Two-Plus-Four Treaty, which should

settle the problems and borders of Germany, but should not be allowed

to freeze the USSR western borders in further bilateral treaties, thus

perpetuating a dangerous precedent.

The Baltic States further consider that border issues in post-war Europe

should not be solved only on the basis of Soviet territorial claims without

participation of the Baltic States, but by opportunities provided within

the framework of the CSCE process, and through negotiations with the Two-Plus-Four

participant states.

The rapid formation of a new security structure in Europe, based

on bilateral treaties requires us to ask the United States Senate

to express its sense in a legally binding conditional form as to

the Two-Plus-Four Treaty and the United States’ non-recognition

policy in regard to the forceful incorporation of the Baltic States into

the Soviet Union.

Endel Lippmaa

On behalf of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Estonia

Andrejs Krastins

On behalf of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Latvia

Ceslovas Stankevicius

On behalf of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Lithuania

Source:

photocopy from original from the Popular Front of Latvia .

(Source: “To the members of the United States Senate”, in: LETTONIE

- RUSSIE, Traités et documents de base http://www.letton.ch/lvx_ap5.htm.)

“During 1990-91, the […] Warsaw Pact disappeared.” [Joseph

Laurence Black, Russia Faces NATO Expansion: Bearing Gifts Or Bearing

Arms? Lanham MD / Oxford UK (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.)

2000, p.6]

January 12, 1991

"U.S. Congress passed a joint resolution authorizing the use of military

force to drive Iraq out of Kuwait."

January 1991

Evidence of the "illegal arming of [secessionist] Croatia and

preparations for the war [was] aired on TV."

May - June 1991

Rising ethnic violence [erupted] in Croatia. Slovenia and Croatia declare[d]

independence.

September 1991

JNA forces openly attack Croat areas (primarily Dalmatia and Slavonia),

starting the Croatian War of Independence. Battle of Vukovar begins.

November 1991

“In November 1991, at the Rome Summit, the Alliance approved

a new strategic concept, which was marked by a shift from the primacy

of collective defense and a decision” in favor of interventionism;

for instance in “intra-state conflicts” (as was to happen in Yugoslavia).

"The

concept emphasized the danger of instability on NATO'S periphery […] Territorial

disputes, ethnic conflicts, and economic crises […] were among the potential

unsettling forces NATO decided to monitor" and deal with. "It

was at the Rome Summit [of 1991] that the Alliance created an institutional

mechanism for dealing with members of the rapidly disintegrating Warsaw

Treaty Organization [...]" In

order to draw Poland, Czechoslovakia and the Baltic into the orbit of NATO,

it was decided in 1991 to set up the "North Atlantic Cooperation Council

(NACC)" that would orchestrate informal military cooperation and coordination

as a first step towards full integration. [Joseph Laurence Black,

ibidem, p.8]

December 1991

The Soviet Union was dissolved on 26 December 1991

1991-1993

“the government headed by Boris Yeltsin "maintained a strongly Western

and reformist orientation. Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev pushed integration

with the West" [...]” [ Joseph Laurence Black, ibidem, p.9]

1993

Joseph L. Black claims that the Yeltsin “government "was

forced to retreat"” from its "strongly Western" course in 1993.

In Black's opinion this must be interpreted as a result of the “elections

of 1993 [that] weakened its position internally.” [ Joseph

Laurence Black, ibidem, p.9] But at the same time, Black is compelled to

admit that in 1993 the Russian leadership was concerned that “Romania

might make a grab for Moldavia, [...] and the Baltic states could follow

the Visegrad group (Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia) into the

[NATO] Alliance” into which they had been informally integrated as recently

adopted members of the North Atlantic Cooperation Council

(NACC).[ Joseph Laurence Black, p.9]

In 1993, “NATO enlargement was already perceived […] as the creation

of a buffer zone in reverse, a means to isolate the new Russia from

continental Europe.”

February 1994

“In early 1994, the unrelenting character of NATO'S plans

to recruit new members began to trigger responses at the highest

level in Russia. In February of that year, Yeltsin felt so threatened

by the possibility of NATO expanding without consulting Russia that he

emphasized his country's opposition to it in his annual message to

the Federal Assembly, and in a separate television address to the nation.[...]

The presidential statement was much stronger than an earlier recommendation

by Kozyrev that Russia work with NATO's North Atlantic Cooperation Council

"to

strengthen mutual trust and developing cooperation" as an alternative

to a "faster expansion of NATO."[…] Interestingly, in 1994 there

was a feeling within [Russian] military circles that Russia might eventually

join NATO itself.” (Joseph Laurence Black, ibidem, p.9)

Late 1996

Madeleine Albright is named first female US Secretary of State. As

UN ambassador, Albright had argued in favor of early military intervention

in Bosnia.

January 31, 1997

“Prime Minister Viktor S. Chernomyrdin of Russia assailed the expansion

of NATO today [...] ''We are warning today that NATO has not changed,''

Mr. Chernomyrdin said, referring to the Western alliance's formation as

a military bulwark against Soviet expansion during the cold war. ''Any

movement of NATO infrastructure to the Russian boundary would do no good.

Rather it would do bad.''”

Edmund C. Andrews, “Russian Hints at Compromise Over NATO”, in: The

New York Times, Jan.31, 1997. http://www.nytimes.com/1997/01/31/world/russian-hints-at-compromise-over-nato.html.)

December 1996

In December 1996, NATO foreign ministers agreed to seek an agreement

with the Russian Federation on arrangements to deepen and widen the scope

of NATO-Russian relations, primarily to offset the largely negative

impact on those relations caused by NATO's decision to enlarge.

March-July 1997

“Despite stern Russian opposition, the Western alliance is planning

a July summit in Madrid at which it expects to invite former Soviet satellites

Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic to join by 1999 [as full members

of NATO]. […]

Solana said in London last week that NATO and Russia were about to

start work on the text of a new strategic security partnership. Citing

unidentified diplomatic sources, Agence France Presse said Monday that

Solana had submitted to Primakov a draft "framework agreement" aimed

at easing Russian concerns about NATO. […]

Solana is to visit four Central Asian republics -- Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan,

Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan [an indication of the West's attempt to establisg

a foothold in Central Asia and recruit new strategic "partners"]-- before

returning to Brussels on Saturday.” (Ian MacWilliam, “NATO, Russia

Upbeat After Solana Visit,” in: The Moscow Times, March 11, 1997).

May 14, 1997

“NATO and Russia reached tentative agreement Wednesday on a new

charter to govern relations after NATO begins its eastward expansion, a

move Moscow has opposed. The deal worked out after a second day

of talks between Russian Foreign Minister Yevgeny Primakov and NATO Secretary-General

Javier Solana follows months of tough negotiations between the two former

Cold War foes and must still be approved by Russian President Boris Yeltsin

and ambassadors from NATO's 16 member nations. Final details were not immediately

available so it was not clear if all differences had been fully resolved.

Both sides hope the deal can be signed at a ceremony May 27 in Paris.”

“Until now, a breakthrough had been blocked by disagreements

over whether the pact should include written guarantees that NATO will

not station military structures and nuclear weapons on the territory of

new member states. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization

has been reluctant to give such guarantees in writing. Shea said

the deal provides assurances to Russia that "the forthcoming enlargement

of NATO is not going to lead to any negative military consequences for

Russia." […] Yeltsin has said he would not sign an unsatisfactory

agreement and told Primakov to take a tough line in the sixth round of

Russia-NATO talks on the pact. Yeltsin had also said repeatedly that

Russia would not back NATO's plans to invite some Eastern European countries

to join the alliance at a summit in Madrid in July. Poland, Hungary

and the Czech Republic are expected to receive the first invitations to

join NATO, though Romania and Slovenia also hope to be in the first

wave. Moscow regards enlargement as a security threat.

”

(N.N., [with Moscow Bureau Chief Jill Dougherty, Correspondent

Betsy Aaron and REUTERS all contributing to this report], “NATO and

Russia reach partnership pact,” in: CNN, May 14, 1997.

http://edition.cnn.com/WORLD/9705/14/russia.nato/.)

May 27, 1997: The Founding Act

| “On May 27 in Paris, Russian President Boris Yeltsin

joined President Bill Clinton and the leaders of the 15 other NATO member

states in signing the "Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation

and Security between NATO and the Russian Federation."”

“[...] the Act "defines the goals and mechanism

of consultation, cooperation, joint decision-making and joint action that

will constitute the core of the mutual relations between NATO and Russia."

The Act establishes a NATO-Russian Permanent Joint

Council which is to begin functioning by the end of September 1997]. The

Act also contains NATO's qualified pledge not to deploy nuclear

weapons or station troops in the new member states and refines the basic

"scope

and parameters" for an adapted Conventional Armed Forces in Europe

(CFE) Treaty.”

“[...] In the second section, which contains the only

concrete action in the Act, NATO and Russia establish the NATO-Russian

Permanent Joint Council. The Council is intended as "a mechanism

for consultations, coordination and, ...where appropriate, for joint decisions

and joint action with respect to security issues of common concern."”

“In the final section of the Act, which deals with political-military

matters, NATO restates that it has "no intention, no plan and no reason,"

[at the moment] to deploy or store nuclear weapons on the territory

of new members. [...]”

“[T]he Act notes that NATO will "carry out

its collective defence and other missions by ensuring the necessary

interoperability, integration, and capability for reinforcement rather

than by additional permanent stationing of substantial combat forces."

[...] But, the Act cautions, NATO "will have to rely on adequate

infrastructure commensurate with the above tasks."”

|

“[D]espite its intention "to overcome the vestiges of past confrontation

and competition and to strengthen mutual trust and cooperation" (in

the words of Solana), the Founding Act was and is viewed by many in Russia

[...] with decided ambivalence.”

“The first section of the Act elaborates the basic principles for establishing

common and comprehensive security in Europe. These principles include strengthening

the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), responding

to new risks and challenges "such as aggressive nationalism, proliferation...,

terrorism, [and] persistent abuse of human rights...," and basing

NATO-Russian relations on a shared commitment to democracy, political

pluralism, the rule of law, respect for human rights, and the development

of free market economies.

NATO and Russia also pledge to refrain from the threat or use of force

against each other or other states, to respect the independence and territorial

integrity of all states and the inviolability of borders, to foster mutual

transparency, to settle disputes by peaceful means and to support, "on

a case-by-case basis" [...], peacekeeping operations carried out under

the UN Security Council.”

“At the signing ceremony, [...] Yeltsin described the Act as containing

"an

obligation not to deploy NATO combat forces on a permanent basis near Russia,"

and as "a firm and absolute commitment for all signatory states." [US-]Administration

officials, on the other hand, made it very clear they consider the Act

to

be only politically, and not legally, binding

and therefore not

requiring Senate approval. Jeremy Rosner, Special Assistant to the President

for NATO Enlargement, said, "the Founding Act itself states explicitly

that the Act does not limit NATO's ability to act independently, and it

does not apply—it's not legally binding —doesn't apply any limitations

on NATO's military policy from the outside."” |

1998

In 1998 the Duma adopted a statement which made it clear “that Russia's

security arrangement and relations with the [North Atlantic Treatry Organization]

Alliance would have to be reviewed if NATO changed its stance towards the

Baltic countries, especially Latvia.”

The Russian reaction was partly due to the fact that the Latvian

government “granted permission to veterans of the Latvian voluntary

SS Legion to celebrate its 55th anniversary (Interfax, 16 March).”

Soon after the old members of the SS had received permission for

an official celebration of their voluntary and eager participation

in Hitler Germany's war of aggression and in repeated acts of genocide,

a war memorial that served to remind people of the fact that the Red Army

had paid a high price in order to defeat Hitler's Wehrmacht, was vandalized

in Latvia. (Joseph Laurence Black, ibidem, p. 215)

NATO emissaries and Western diplomats nonetheless continued their concerted

effort to integrate Latvia (as well as Lithuania and Estonia) into the

Western alliance. In July 1998, “Strobe Talbott's participation

in the first session of the Commission for Partnership between the

United States and the Baltic Countries” [Black, ibidem, p.219]

was an indication that the US were working determinedly to achieve NATO

integration. “Talbott endorsed a communiqué which

implied that the Baltic countries were prepared for entry into NATO.”

(Black,ibidem, p.219) Clearly, “the United States

was ignoring Russia's hope for a “blockless” European security system.”

(Joseph Laurence Black, ibidem, p.219)

[1998]

J.L. Black mentions “Russia's [...] proposals, in Stockholm,

of a northern secturity system” and the fact that this was “summarily

dismissed by Sweden and the Baltic states [….]”.

In 1998, Norway expelled five Russian diplomats on charges of spying,

as that country got ready for “a large scale NATO military exercise (Strong

Resolve 98), the venue of which was Norway, the North Sea, and the

Norwegian Sea […].” For observers in Russia it was clear that

“the expulsion of Russian diplomats” was linked “directly to the war

games.” (Joseph Laurence Black, ibidem, p.216)

“In May [1998], Adamkus informed a Russian interviewer that Lithuania's

aspiration to join NATO should not be viewed as opposition to Russia. He

went on to predict that Russia itself would eventually join"NATO

as the all- European security system." [...]

Solana told a Russian NTV audience on 26 May that whereas “every

country has the right to choose security structures in which it wants to

participate,” NATO will “take Russia's opinion [about Baltic entry]

into account.”[...]

In June, he went so far as to moot Russian membership and spoke

tentatively, while visiting the Baltic capitals, of the possibility

of a separate security scheme for the Baltic region to include Russia.

This

concept, even though speculative, cheered some Russian observers.[...]

Russia itself was encouraged to play a greater role in NATO activities,

a fact evidenced by an agreement that a platoon of Baltic Fleet marines

would join a military exercise in Northern Denmark in late May, and

that Russia would send observers to the Baltic Challenge 98,

a NATO maneuver scheduled for Lithuania in July.[...]” (Joseph

Laurence Black, inbidem, p.217)

In view of the obvious fact that the West was bent on including Lithuania,

Latvia and Estland in its NATO military alliance, Russia's government made

it quite clear that “military integration of the Baltic countries with

NATO was unacceptable.” (Joseph Laurence Black, ibidem,, p.219)

The US elites wanted the continuation of a bloc dominated by them,

and they wanted to exclude Russia from membership in that bloc.

“A large-scale NATO exercise near Klaipeda was being projected and

NATO's plans to set up a corps headquarters in Poland's Szczecin

were ominous. Spokesmen for the Russian military claimed that the new corps

represented a direct violation of Article IV of theFounding Act.”

[Joseph Laurence Black, ibidem, p.219]

Jan. 13, 1998

Renewed crisis in Iraq as President Saddam Hussein bans weapons team

led by US inspector.

Feb. 23, 1998

US diplomat Robert Gelbard publicly calls KLA [Kosova Liberation Army

= UCK] "without any question a terrorist group"

Aug. 20, 1998

US launches cruise missile attack on Afghanistan and Sudan

in response to Nairobi and Dar Es Salaam embassy bombings. In polls,

significant numbers of Americans say they believe the attacks were staged

to divert attention from the Lewinsky scandal.

Sept 23, 1998

UN Security Council approves Resolution 1199 demanding cease-fire,

Serb withdrawal and refugee return and calling for unspecified "additional

measures" if Serbia refuses to comply.

Sept.24, 1998

In Vilamoura, Portugal, NATO Defense Ministers give NATO's Supreme

Commander permission to issue an activation warning (ACTWARN) -- the first

real step in preparation for airstrikes.

Sept. 30, 1998

At principals committee meeting, US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright

pushes for airstrikes against Serbia. Administration briefs Capitol Hill

on the plan. Meeting Congressional resistance, the Administration notes

it has no plans to send ground troops to Kosovo, even as peacekeepers.

March 9, 1998

"Contact Group" countries (US, UK, France, Germany, Italy and Russia)

meet in London to discuss Kosovo.

Jan.15, 1999

The Racak Massacre. In retaliation for KLA attack on 4 policemen, Serb

security forces kill 45 Kosovo Albanians. KVM Director William Walker arrives

on scene following day, forcefully blames Serbia in front of television

cameras. Milosevic refuses to allow war crimes prosecutor Judge Louise

Arbour to visit Racak.

Jan. 19, 1999

In light of Racak massacre, National Security Adviser Sandy Berger

reconvenes Principals Committee. Albright's push for military ultimatum

wins the day. At same time, NATO SACEUR Wesley Clark and NATO military

council chairman Gen. Klaus Naumann meet with Milosevic in Serbia in tense

seven-hour meeting. Milosevic claims Racak was staged by the KLA, calls

Clark a war criminal.

Jan. 27, 1999

Joint statement on Kosovo by Albright and Russia's Ivanov. Clinton

meets with foreign policy team to discuss post-Racak strategy.

Mar.24, 1999 The Kosovo air war begins.

April 28, 1999

House of Representatives votes largely along party lines to reject

a resolution supporting air war, demonstrating continuing mistrust of

Clinton and his Balkans policy.

May 7, 1999

In night of extensive bombing, NATO planes [...] target Chinese Embassy

in Belgrade, killing 3 and wounding 20. [...] In a separate incident, a

NATO cluster bomb misses an airfield and strikes a market and a hospital

near Nis

May 11, 1999

Chernomyrdin and Jiang Zemin confer in Beijing, criticize bombing.

May 27, 1999

In secret Bonn meeting, US Defense Sec. Cohen meets with NATO defense

ministers to discuss possible invasion; allies conclude that governments

must decide soon whether to assemble ground troops. International War Crimes

Tribunal announces indictment of Milosevic and four other FRY and Serbian

officials.

May 30, 1999

NATO bombs a bridge in Varvarin, killing and wounding civilians on

board a passenger train that was crossing the bridge..

June 1, 1999

Final round of talks between Talbott, Chernomyrdin and Ahtisaari

begins. Discussion continues up until negotiators depart for Belgrade two

days later. FRY informs Germany of its readiness to accept G8 principles

for ending bombing.

June 8, 1999

During G8 talks in Cologne, allies and Russia reach agreement on possible

UN resolution to sanction the peace deal.

June 9, 1999

After more discussions, NATO and FRY officials finally initial a Military

Technical Agreement to govern the Serb withdrawal from Kosovo.

June 10, 1999

Solana requests suspension of NATO bombing, and the Security Council

adopts resolution 1244 permitting the deployment of the international

civil and military authorities in Kosovo.

June 12, 1999

In a move that surprises allied commanders, approximately 200 Russian

troops leave Bosnia, travel through Serbia and enter Kosovo before NATO,

taking control of Pristina airport.

Oct. 7, 2001

October 7: (9 p.m. local time): the United States, supported by

Britain, begins its attack on Afghanistan, launching bombs and cruise

missiles against Taliban military and communications facilities and suspected

terrorist training camps. Kabul, Kandahar, and Herat were hit.

In 2002, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1441

which called for Iraq to completely cooperate with UN weapon inspectors

to

verify that Iraq was not in possession of WMD and cruise missiles.

[March 2003]

The Second Gulf War usually refers to the Iraq War (March 2003

to December 2011), a two-phase conflict comprising an initial invasion

of Iraq led by US and UK forces and a longer, seven-year phase of occupation

and fighting with insurgents.

[April 22-23, 2010]

“Foreign Minister Urmas Paet met with president of the

USA think tank the Brookings Institution and former American under secretary

of state Strobe Talbott and former foreign policy leader of the

European Union Javier Solana to discuss Estonia’s activities

in NATO and the European Union and developments in Russia, Ukraine

and Georgia. Foreign Minister Urmas Paet stated that Strobe

Talbott’s work as an important creator of American foreign policy during

the presidency of Bill Clinton set a foundation for Estonia and many

other nations to join NATO. “Now, as a member of NATO and the European

Union, Estonia has become a strong supporter of extending of the values

of these organisations,” said Paet. “We feel it is especially

important to share our experiences with acceding states. Estonia and other

like-minded nations are attempting to support the European Union’s Eastern

Partners and keep them in focus. Within the framework of these endeavours,

we plan to establish an Eastern Partnership training

centre at Tallinn’s Estonian

School of Diplomacy,”

said Foreign Minister Paet. Paet noted that co-operation and exchanging

ideas with various think tanks, including the experts at the Brookings

Institute, will certainly be helpful for the establishment of the training

centre. Another topic discussed was European Union-USA co-operation. According

to Foreign Minister Urmas Paet, close co-operation between the European

Union and the USA is the basis for stability, economic growth, and lasting

development in the Euro-Atlantic region.[...]” (N.N.,“[Estonian] Foreign

Minister Paet Met with Javier Solana and Strobe Talbott”, in: http://www.vm.ee/?q=en/node/9282

[Press Release on the occasion of an official meeting in Talinn, April

22-23, 2010])

Olivier Zajec, "The Good Ones, the Brute and Crimea:

The Anti-Russian Obsession,"

in: Le Monde diplomatique, Vol. 61, No. 721 (April, 2014),

p. 1 and p.4.

September 2012

In 2012, the Los Angeles Times reported former Presidential candidate

Mitt Romney as saying that “Russia is a geopolitical adversary

[…] My own view is that Russia has a very different agenda than ours and

that we ought to recognize that, and that we should pursue our interests,

but recognize Russia as having a different course.” (Mitchell Landsberg

and Robin Abcarian, “Mitt Romney Calls Russia 'Geopolitical Adversary',”

in: The Los Angeles Times, Sept.10,2012 http://articles.latimes.com/2012/sep/10/news/la-pn-mitt-romney-russia-syria-20120910.)

March 23, 2014

“Russia's adversarial behaviour neccesitates a strategic response,

General Philip Breedlove, Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) has

said. […] As for NATO's future, he said Crimea means: "changing

our deployment, readiness and force structure. We have moved F-16s from

Italy to Poland and the Baltics and we have shifted some of our naval assets

to be engaged in the Black Sea. There are other things we are considering

but I cannot make that public right now." Asked if the alliance

should put countervailing pressure on Moscow by conducting exercises close

to the border of Kaliningrad, its enclave in the Baltic region, Breedlove

said no. "I don't think that would be a good idea. There are lots of

ways we can position forces by moving them eastward to reassure our allies.

But having an exercise around Kaliningrad would be very escalatory and

not help things," he said. ” (Brooks Tigner, “Russia behaving 'like

an adversary', says SACEUR,” in: IHS Jane's Defence Weekly, March

23, 2014 http://www.janes.com/article/35841/russia-behaving-like-an-adversary-says-saceur.)

In March, 2014, “Mr. Romney's assertion in the 2012 presidential debates

that Russia was America's top geopolitical foe […]” was practically a repeat

of what Romney had said in 2012. (Mark Sappenfield, “Mitt Romney: Russia

not an enemy, it's 'our geopolitical adversary.',” in: The Christian Science

Monitor, March 23, 2014 http://www.csmonitor.com/USA/DC-Decoder/2014/0323/Mitt-Romney-

Russia-not-an-enemy-it-s-our-geopolitical-adversary.-Huh-video.)

March 24, 2014

“MADRID – Even Mikhail Gorbachev, who presided over the dissolution

of the Soviet Union with scarcely a shot fired, has proclaimed his support

for Russian President Vladimir Putin’s annexation of Crimea. The people

of Crimea, he says, have corrected a historic Soviet error. Gorbachev’s

sentiment is widely shared in Russia. [...]”

Javier Solana, “Stabilizing Ukraine”, in: Project Syndicat, March 24,

2014. http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/javier-solana-identities-three-issues-

that-must-be-addressed-in-the-wake-of-russia-s-annexation-of-crimea

April 1, 2014

“Although Russia’s President Vladimir Putin’s saber rattling is attempting

to restore some of the splintered Soviet Empire, and restoring its grandeur

as a Eurasian power to be reckoned with, that train has long passed. […]

as a long-term adversary to the U.S., Russia is no match. […] The obvious

ascending economic superpower of this century’s second half is destined

to be China. Its incredible growth is also, surprisingly, developing

a consumer demand populace, second only to the U.S. today. Even in the

military sector, which the U.S. has dominated since the second world war,

China is rapidly expanding, while the U.S. is diminishing. What seems

to make China less of a geopolitical threat than Russia is that Beijing

does not now harbor confrontation with the European Union, or the West

in general. It is thereby not threatening the U.S.’s integral NATO and

Eurocom Alliance, or other direct interests. But this could change

[...]” (Morris Beschloss, “Is Russia or China America’s Most Dangerous

Geopolitical Adversary?,” in: The Desert Sun (A Gannett Company newspaper),

April 1, 2014 http://www.desertsun.com/story/beschloss/2014/04/01/is-russia-or-china-

americas-most-dangerous-geopolitical-adversary/7174573/.)

April 6, 2014

N. Krainova points out different assessments of “the new government

in Kiev, which Moscow has said is illegitimate but the West recognizes.”

She then goes on to say that “EU foreign ministers met in Athens to discuss

the ongoing Ukraine crisis [...] as NATO prepares to boost its military

presence in Europe” “Concerned about possible military aggression from

Russia, Poland has asked NATO for protection. Polish Prime Minister Donald

Tusk said Saturday that "the strengthening of NATO's presence [in Poland],

also military presence, has become a fact and will be visible in the coming

days, weeks," Reuters reported. NATO will draft a plan for the deployment

of its forces by mid-April. NATO's plans for Poland were publicized a day

after Russia recalled its top military representative to NATO, General

Valery Yevnevich, for consultations. Russia, for its part, apparently

sought to ease Poland's fears last Thursday.” (Natalya Krainova, “Protesters

Storm Buildings in Ukraine as West Ponders Next Move,” in: The Moscow Times,

Apr. 6, 2014)

:

Regarding the Soviet débâcle in Afghanistan

that was one of the factors leading to Gorbachev's decision to seek an

end to the Cold War, see for instance:

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1499983/Soviet-invasion-of-Afghanistan

- Jan van Houten (compiler)

Go to Art

in Society # 14, Contents

* |

.

| (1) In hindsight, it is possible to say that Ostpolitik and

the arms race, employed by the West, functioned like the proverbial carrot

and the stick. |

(2) Source: N.N., “Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, ”, in:

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/

1499983/Soviet-invasion-of-Afghanistan |

| (3) Joseph Laurence Black, Russia Faces NATO Expansion: Bearing

Gifts Or Bearing Arms? Lanham MD / Oxford UK (Rowman & Littlefield

Publishers, Inc.) 2000, p.7 |

(4) “[A] crucial early suggestion of German Foreign Minister

Hans-Dietrich Genscher, advanced in January 1990, [was] that eastern Germany

[would] forever remain free of NATO troops. The purpose of Genscher's proposal

was to help make German membership in NATO palatable to the Soviet Union

by assuring that after unification NATO forces would not move

closer to the borders of the Soviet Union than they had been

before unification.”

(Peter E. Quint, The Imperfect Union: Constitutional Structures of

German Unification, PrincetonNJ (Princeton Univ.Press) 1997, p.273.) |

| In January, 1990, thus during the period leading up to the Two Plus

Four Treaty, “a crucial [...] suggestion” regarding the “military status

of eastern Germany had been made by German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich

Genscher” in a conversation with Gorbachev. Genscher had said “that

eastern Germany [should] forever remain free of NATO troops. The purpose

of Genscher's proposal was to help make German membership in NATO

palatable to the Soviet Union by assuring that after unification NATO forces

would not move closer to the borders of the Soviet Union than they had

been before unification. But "as a result of western – particularly

American – influence," the final agreement did not make as much of

a concession to the Soviet Union on this point as Genscher had originally

proposed.” Gorbachev agreed that Germany should be fully sovereign but

no NATO troops other than a limited number of German units integrated in

NATO should be stationed in what had been the GDR (so-called East Germany).

(Peter E. Quint, The Imperfect Union: Constitutional Structures of German

Unification, PrincetonNJ (Princeton Univ.Press) 1997, p.273.) |

“The "Treaty on the Final Settlement With Respect to Germany" more

commonly known as the "Two Plus Four Treaty" was the final peace treaty

negotiated between the Federal Republic of Germany, the German Democratic

Republic, and the Four Powers that occupied Germany at the end of World

War II in Europe - France, the United Kingdom, the United States and the

Soviet Union.The treaty was signed in Moscow on September 12, 1990. The

treaty paved the way for the German re-unification, which took place on

October 3. Under the terms of the treaty, the Four Powers renounced all

rights they formerly held in Germany and re-united Germany became fully

sovereign again on March 15, 1991. The Soviet Union agreed to remove all

troops from Germany by the end of 1994. Germany agreed to limit its combined

armed forces to no more than 370,000 personnel, no more than 345,000 of

whom were to be in the army and air force. Germany also agreed it would

never acquire nuclear weapons. [...]”

(The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars http://legacy.wilsoncenter.org/coldwarfiles/index

-58013.html.) |

| “[T]he four Allied powers [...]declared that they "hereby terminate

their rights and responsibilities relating to Berlin and to Germany as

a whole" [….] Consequently, "the united Germany shall have

… full sovereignty over its internal and external affairs." [...]”

(Peter E. Quint, The Imperfect Union: Constitutional Structures of German

Unification, PrincetonNJ (Princeton Univ.Press) 1997, p.275) |

| “In accordance with the agreement reached by Kohl and Gorbachev in

the Caucasus, article 6 of the Two Plus Four agreement permits united Germany

to belong to “alliances, with all the rights and responsibilities arising

from them.” (Peter E. Quint, The Imperfect Union: Constitutional Structures

of German Unification, PrincetonNJ (Princeton Univ.Press) 1997, p. 273) |

| “[According] to article 5, section 3 [of the Two Plus Four Treaty],

German troops, including German troops integrated in NATO, could be stationed

in former GDR territory after the withdrawal of Soviet troops, but foreign

troops may never be stationed in that territory, nor may they be "deployed"

there.

Thus, after the departure of Soviet troops, only German NATO forces, but

not NATO forces of other nations, may be stationed or deployed in eastern

Germany. Accordingly, one part of unified Germany – the territory of the

former GDR – will remain under permanent limitations with respect

to the presence of foreign armed forces.” (Peter E. Quint, The Imperfect

Union: Constitutional Structures of German Unification, PrincetonNJ (Princeton

Univ.Press) 1997, p. 273)

“As a consequence of German unification, “NATO's domain was extended

eastward to include the territory of the former GDR.” [Joseph Laurence

Black, Russia Faces NATO Expansion: Bearing Gifts Or Bearing Arms?

2000, p.6] |

| Commenting on the German Soviet Treaty of Sept 14, 1990, Serge Schmemann

also noted that "Western diplomats" played down the significance of promises

of partnership and cooperation, saying that the wording of the treaty "was

for domestic consumption [in Russia], to demonstrate to a nation reared

on the accounts of Soviet sacrifices in World War II that a united Germany

was prepared to put its peaceful intentions on paper." The New York Times

probably echoed statements by U.S. diplomats when it emphasized that "the

treaty included few concrete agreements" - suggesting in fact that the

"pledges of peace and cooperation" were mere words without much concrete

significance. (Serge Schmemann, “Moscow and Bonn in a 'Good Neighbor' Pact,”

in: The New York Times, September 14, 1990) |

| In January 1992, the so-called Vance peace plan was signed that was

supposed to lead to the creation of 4 UNPA zones for Serb-controlled

territories, and that brought an end to large-scale military operations

in Croatia. UNPROFOR forces arrived to monitor the peace treaty.

In February-March 1992, the Carrington–Cutileiro peace plan marked an

attempt to prevent Bosnia-Herzegovina from sliding into war. It proposed

ethnic power-sharing on all administrative levels and the devolution of

central government to local ethnic communities. On March 18, 1992,

all three sides signed the agreement but ten days later, Alija Izetbegovic,who

represented the Bosniak (Muslim) side, withdrew his signature and declared

his opposition to any type of partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina. A day

later, the government led by Izetbegovic declared independence and

the war began.

|

“[T]he German government's efforts to create national military command

and planning structures, or a Fuehrungs- kommando [...]” [p.228]

[had] “the purpose […] to facilitate German particpationin

multilateral out-of-area military operations

that are not under NATO command. [….] No longer restricted

to the defense of German territory, the Bundeswehr

has been deployed

for an increasingly wide range of out of area missions. [...] [H]owever,

one must […] differentiate between […] willful use of force [a]

in the pursuit of national interests” and [b] German participation

in military interventions

“dictated by the pressures

[….] and […] expectations of Germany's partners” – notably the U.S. [or

France, in the context of interventions in the Sahel zone]. [p.229]

(John S. Duffield, World Power Forsaken: Political Culture, International

Institutions, and German Security Policy After Unification. Stanford

CA (Stanford University Press) 1998.)

. |

“Peter Rodman of the Nixon Center, echoing

conservatives in Congress and the press, argued that the Act "promises

to complicate NATO decision-making in future crises in Europe or the Middle

East." He acknowledges, "it's not at all clear that we bought Russian acquiescence

in NATO enlargement..." but concludes, "having paid this price to the Russians,

we have no choice but to go forward. The worst of all worlds would be to

have paid this price and then not proceed with the NATO project to be launched

at Madrid."

The Act's reception among Russians was equally diverse. While in

Paris, Yeltsin praised the document. But on the eve of the Act's signature,

Yeltsin cautioned that NATO would "fully undermine" its relations with

Russia if it expanded to include any of the former Soviet Republics,

generally understood to pertain to the Baltics and Ukraine. (Foreign

Minister Primakov said Russia remains "categorically against" NATO expansion

to include any former Soviet republics.) Sandy Berger, the president's

National Security Advisor, when briefing the press four days after

the Paris Summit, said, "We have made it very clear in the Founding

Act and in all of our discussions publicly and privately with the Russians

that we don't believe that any nation is or should be excluded from

potential membership in NATO if they meet the criteria and they seek

to be members."

Yeltsin, in his radio address to the Russian people on May 30, described

the Act as an effort "to minimize the negative consequences of NATO's expansion

and prevent a new split in Europe." He then described the agreement—inaccurately,

according to Western officials—as "enshrining NATO's pledge not

to deploy nuclear weapons on the territories of its new member countries,

not

[to] build up its armed forces near our borders...nor carry out

relevant infrastructure preparations."”

(Jack Mendelsohn, “The NATO Russian Founding Act,” in:

The Arms Control Association https://www.armscontrol.org/act/1997_05/jm.) |

| REGARDING THE RUSSIAN LEADERSHIP'S VIEW OF NATO EXPANSION, see:

Viktoriia Ivanova, “Rasshirenie NATO bylo i ostaetsia nepriemlemym”

[NATO Expansion Was and Remains Unacceptable], in: Nezavisimaia gazeta,

May 14, 1998.

Aleksei Baliev, “Protiv kogo druzhat Amerika s Baltiei?” [Against Whom

Did America Become Friendly with the Baltics?], in: Rossiiskaia gazeta,

July 17, 1998.

Nikolai Lashkevich, “NATO uzhe pod Klaipedoi” [NATO Already Near Klaipeda],

in: Izvestiia, July 10, 1998.

Igor Korotchenko, “Al'ians ukrepliaet pozitsii na Baltike. Formirovanie

datsko-pol'sko-germanskogo korpusa pereshlo v zavershaiushchuiu fazu” [The

Alliance Strengthens Its Position on the Baltic: The Formation of a Danish-Polish-German

Corps Moves towards Completion], in: Nezavisimoe voennoe obozrenie, No,

48, Dec.17-24, 1998. |

| As editor-at-large of Time magazine, Strobe Talbott had

said (in the first January issue of 1990) that "[i]t is about

time to think seriously about eventually retiring [i.e. dissolving] the

North Atlantic Treaty Organization." (Joseph Laurence Black, ibidem,

p.7) As a member of an important Cold War think-tank and a career diplomat,

Talbott may have been playing his pre-meditated role of "lulling"

Gorbachev whom he made "man of the year" in January 1990. Others involved

in such sweet-talk were Mr. Genscher and Mr. Kohl. Gorbachev was deeply

concerned that the arms race and the concomitant tension could lead to

accidental unleashing of a nuclear holocaust. He, like others in the Soviet

leadership, had also become thoroughly social-democratic ideologically,

seeking a "third way" characterized by democracy and a "socialist market

economy" - the latter a tendency that took into account "consumerist" desires

of the common people, sweeping aside rigorous bureaucratic central planning.The

decisive weakening of rigorous central planning and the transformation

of the plan into a broad framework that left much to the dynamics of the

market had been the central objective of the economic reforms that were

based on proposals by Prof. Liberman. Gorbachev and others seem to have

thought that the West German welfare state that had been strengthened by

the Brandt government came pretty close to their own idea of reformed "socialism."

They took the promises of West German Ostpolitik at face value,

and as fairly idealistic humanists they hoped for a real understanding,

a true entente, and especially - quite concretely - stepped-up economic,

scientific and cultural cooperation with an eventually united Germany.

It was clear to them that real entente required the dissolution of military

alliances (both the Warsaw Pact and NATO had to be dissolved). This, to

them, was a matter of good will and honesty. |

[The Gulf War of 2003ff.]

Prior to the war, the governments of the United States and the United

Kingdom claimed that Iraq's alleged possession of weapons of mass destruction

(WMD) posed a threat to their security and that of their coalition/regional

allies.[...]

In 2002, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1441

which called for Iraq to completely cooperate with UN weapon inspectors

to verify that Iraq was not in possession of WMD and cruise missiles. Prior

to the attack, the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection

Commission (UNMOVIC) found no evidence of WMD, but could not yet verify

the accuracy of Iraq's declarations regarding what weapons it possessed,

as their work was still unfinished. The leader of the inspectors, Hans

Blix, estimated the time remaining for disarmament being verified through

inspections to be "months".

After further investigation had been undertaken, subsequent

to the illegal invasion, the US-led Iraq Survey Group concluded that

Iraq had ended its nuclear, chemical and biological programs in 1991 [...].

|

|