|

THE PRE-HISTORY OF THE KOREAN WAR During Japan's occupation and subjection of Korea as a colony, resistance to foreign rule did never completely die.(1) The common people rejected the new authority even more than the old one. Among the yangban and the urban 'middle' class, resentment of Japanese rule was prevalent, even though, soon enough, parts of the old yangban 'elite' and of the merchant class saw the advantage of collaboration with the new rulers.(2) Many students, either from rural yangban families (thus the landlord class) or with an urban middle class background, were actively engaged in pro-independence activities, staging demonstrations.(3)

Other members of the elites supported the nationalist pro-independence circles more quietly and carefully, among them Kim Song-su, a "wealthy textile corporation founder and educational philanthropist."(6) Among the educated, especially writers and intellectuals, modern concepts of liberalism and socialism circulated. This was in part so because some of them had pursued advanced studies in the United States and in Japan. It was here that they became acquainted with new ideas.(7) Missionaries, many of them from the U.S.A., also brought new ideas of a sort to Korea. Under their influence, a man who later on became dictator in South Korea, adopted the new religion, deserting Confucianism. His name was Syngman Rhee. He became a missionary, but he also became active in a nationalist pro-independence circle. Running into difficulties, Syngman Rhee left Korea for the United States in 1912, returning only in the summer of 1945.(8) Resentment of Japanese rule among quite a few urbanites lead to discussions and conspirational meetings. In contrast, the strong rejection of foreign domination among peasants led to the formation of a guerilla army in the 1910s. This army became known as the "righteous army."(9)

It was mainly an insurrection of peasants who were following the example of previous peasant revolts. The insurrection flared up here and there; in fact it would be more correct to speak of a number of regional insurrections, and this continued throughout a number of years in the 1920s, until the last rebellions were finally put down.

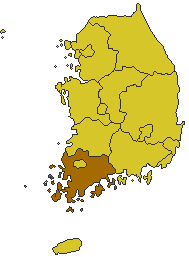

Being traditional revolts, these insurrections were more inspired by native agrarian concepts of equity and mutual help than by modern ideologies and theories. * * * In Japan, however, the October Revolution had not remained unnoticed among intellectual circles or in the trade union movement that had formed here in the 1890s, mainly due to contact with sailors in the U.S. merchant marine. When the news about the revolution in Russia spread, it had immediately affected a number of Japanese socialists. This was not without consequence in Korea and Taiwan, due to the movement of persons between Japan and its colonies. Thus, it was in fact inevitable that among the more radical critics of the situation in Korea, the wish to form a communist movement would grow. As Allan Millet notes, "the first Korean Communist Party" was already established in 1918 by exiles in Soviet Russia.(10) Soviet Russia was, however, not the only safe haven, for left-wing Korean revolutionaries. Others had gone to China where they established a "Provisional Government" of Korea, inspired by Woodrow Wilson's much-publicized endorsement of national self-determination and filled with republican zeal. South China was Sun Yatsen's republican turf, and Shanghai a center of the leftist Chinese working class movement. So the "Provisional government" of Korea chose Shanghai as its seat. And here, in Shanghai, just a year or two after a Korean CP had been founded in Irkutsk, a number of Korean socialists, "around Yi Tong-hwi, a former Korean imperial army officer and charismatic anti-Japanese Righteous Army leader," formed a party that embraced socialism, called the Koryo Communist Party.(11) "Tong-hwi took his Koryo Communist Party into a coalition with the Provisional Government and won the Comintern's recognition as the legitimate Korean Communist Party in 1921, which meant money and support that was denied the rival Irkutsk faction."(12) But already one year later, "[i]n 1922, the Russians despaired of ever bringing the Shanghai and Irkutsk factions together and declared both parties defunct. Still, they brought Yi Tong-hwi to Vladivostok to run a Far East Committee Korean Bureau as an anti-Japanese agency of the Russian Communist Party."(13) It was clear that both the Korean Leftists based in Soviet Russia and those in Shanghai would try to establish links to Koreans in the motherland, in order to form debating circles, organize workers and peasants, and found a party inside Korea. And thus, indeed, "the Korean Communist Party [...] was formed in 1925 [....]" in Korea.(14) Exposed to the organs of repression of the Colonial administration, it faced the gravest difficulties, and by 1941, when Japan started the Pacifc War and political activism became even more dangerous then before, the Korea-based party, led by Pak Hon-yong,"had been destroyed [already] four times [...]."(15) Pak Hon-yong had only been "twenty-one years old when he joined the Shanghai faction in 1921 [...]"He is described by Millet as"[i]ntelligent, attractive, honest, and courageous, [...] the Korean Kirov, the noble revolutionary to good to escape his rivals. The Japanese imprisoned him in 1925-1929 and again in 1933-1939, and his torture and squalid isolation during the latter period so imbalanced him that the Japanese paroled him as mad and harmless. Pak was angry, not insane, and he organized another Korean Communist Party. With the Japanese police in hot pursuit, Pak fled [from Seoul] to South Cholla [S. Cheolla; Jeolla] province, a hotbed of radicalism and resistance" even in these dangerous years.(16) "Finding anonymity as a brickyard worker in 1941, Pak stayed in touch with underground organizers" – prepared to return to Seoul when the time was ripe.(17) As Japan turned more and more militaristic, the situation for those who attempted to work for Korean independence in the Korean motherland became more and more difficult. Clandestine pro-independence circles in Korea, regardless of whether they were conservative, liberal, or left-wing, faced stark repression. Millet names “some nationalist leaders [who] survived” Japanese repression, which entailed “the burden of constant police surveillance and job discrimination [...].”(18) It was since the late 1930s that more and more Nationalist liberals, conservatives, and socialists who saw political work as almost impossible in Korea, had gone to China. This was the time of the official detente between the KMT regime and the Communist Chinese revolutionaries (in 1937). .Encouraged by Chiang Kai-shek's regime, quite a few of these exiled Koreans joined the “Korean Liberation Army” that was formed in 1941.(19)Formally, the KLA was not established by the KMT or its US advisers but by the "Provisional Government" of Korea established in Shanghai in the wake of WWI.(20) “[U]nits of the KLA participated on the allied side in

the Chinese and Southeast Asian theatres” on the side of KMT forces and

the British (21) – but not in Korea

which remained firmly under Japanese control. Although most commanders

of the KLA were conservatives or liberals, at least one of its generals

was a leftist who would later opt to go to the North rather than the South

of Korea.

Others anti-colonialist Koreans, mostly left-wing radicals, went north across the Yalu River at the time, hoping to make the step from theory to revolutionary practice. Thus, in the 1930s, a left-wing anti-Japanese guerilla, inspired undoubtedly by the righteous army, was formed in the Japanese occupied puppet state, Manchukuo. The new guerilla movement was recruiting both Korean peasants who had settled in this Chinese Northeastern province [dong bei] and Korean workers recruited in the Korean motherland and transferred to Manchukuo.(22) A number of idealistic urban youths from the motherland are said to have joined this guerilla, as well. The communist leaders of the guerilla in Manchukuo apparently hoped to form a people's army that would liberate Korea. They were in touch with Mao Zedong and other Red Chinese leaders. It seems that the Soviet Union did not openly provide assistance to them at the time, as Stalin had concluded a neutrality treaty with the Japanese government. Eager to avoid a second front in East Asia by all means, he was ready to stick to the letter of the treaty, in order to provide absolutely no pretext for a Japanese offensive against Russia. Even though the Korean guerilla movement in Manchukuo

was obviously inspired by the 8th Route Army in China, its different units

remained too weak and ill-equipped to withstand Japanese suppression campaigns.

* * * When Hitler-Germany was smashed and its forces surrendered on May 8, 1945, Soviet Russia was finally ready to declare war on Japan. The Red Army pushed into Manchuria and then, into Korea. The left-wing Korean guerilla returned to the motherland together with the Red Army. On September 15, 1945, Japan surrendered, thereby officially ending the Japanese occupation of the Korean peninsula. Already a week before that date, on September 8, 1945, US forces landed in Incheon [Inchon], in the Southern part of Korea.(23) And now, many surviving “members of the KLA returned” to the South, often on US navy vessels.(24)This return occurred “during late 1945 and 1946.(25) Considered trustworthy by the Americans, many of these

men were integrated into the newly formed National Police and South Korean

army. Important members of the KLA, “including Generals Ji and Lee,

became part of the South Korean government” –

an un-elected civil administration that the American occupation authorities

installed in 1946 as a so-called "interim government" answerable

to the US Military Government in Korea.(26)

Prior to the arrival of the Americans and thus ahead of the civil administration they would install, the “People's Republic of Korea” had been proclaimed, however, “by a center-left politician, Yuh Woon-Hyung."(27)That important event occurred in Seoul on September 6, 1945 – thus two days before the US troops landed in Incheon. The proclamation of an independent Korean republic claiming to represent all of Korea was not only disregarded but illegalized by the Americans, and Yu Woon-Hyung was murdered.(28) His attempt to safeguard unity was rejected by the US occupation force. It was also critiqued by the Leftist resistance that had fought the Japanese, and by the collobarators and the other rightists who would form the South Korean administration and the security apparatus that the Americans hastened to put in place.(29) It is possible that Yuh Woon-Hyung's proclamation was no more than an empty declaration, not backed up by solid popular support. It was the radical Left that enjoyed such support, especially among the majority in the countryside, the peasants, who were decisive in a still very agrarian society. American declassified documents confirm this. Peasants were suppressed by the landlord class and loathed the burden of high rent levels. When assuming control of Korea South of the 38th parallel, the US occupation authorities were surprised by the strength of left-wing implantation in the entire country: “they found left-wing people's committees active in most areas.”(30)“Faced” with a strong left and “with mounting popular discontent, in October 1945 Hodge established the Korean Advisory Council.”(31) (This was in fact a forerunner of the so-called "interim government.") In view of the fact that the South Korean mainland was already rife with discontent and graced with a strong left-wing movement in 1945, it becomes clear that the situation on Cheju [Jeju] Island three years later – when that island became the site of a massive revolt that erupted in April 1948 and lingered until 1954 – was not exceptional. “By late 1947, an estimated 80 percent

of Cheju islanders were SKLP members [members of the South Korean Labor

Party] or loyalists [sympathizers of this left-wing political organization].(32)

As

the American occupation commander, Gen. John R. Hodge, put it [later

on, when questioned about the insurrection, probably in the context of

a Congressional hearing], Cheju was "a truly communal area peacefully

controlled by the [local] people's committee." [...]”(33)

In 1945, however, the Americans in charge of Korea's

South were not amused when they recognized the fairly solid presence of

the Left in their occupation zone. They brought in a man they trusted and

who had already cooperated with them.

This man was Syngman Rhee, the former missionary and YMCA coordinator, married to an Austrian woman (Franziska Donner) who lived in the USA since 1912 (most of the time in Hawaii, but since Nov. 1939, in Washington, D.C.).(34) Shortly after Japan's unconditional surrender “on September 2, 1945, Rhee was flown to Tokyo aboard a US military aircraft.”(35) After “a secret meeting with [General] Douglas MacArthur” (who was in charge of Japan and Korea as military commander), Rhee was flown to Seoul (in mid-October 1945).(36)Upon his arrival in Korea, Rhee was almost immediately made “president of the Independence Promotion Central Committee [...], chairman of the Korean People's Representative Democratic Legislature [...], and president of the Headquarters for Unification [...]” – thus of political institutions that presaged the Advisory Council of October 1945 and the interim government of 1946, and that prepared his rise to the presidency in 1948.(37) His credentials were obvious: he was “strongly anti-communist,”

(38)

he was a Christian, he had a Western wife, and he had consecutively

lived in the US for 33 years. In addition, he had succeeded to build contacts

and form close ties with US politicians between 1939 and 1945.

“In December 1945,

a conference convened in Moscow to discuss the future of Korea.A 5-year

trusteeship was discussed, and a US-Soviet joint commission was established.

Contrary to an agreement reached between the Roosevelt administration and the Soviet government that a US-Soviet Cooperation Committee should prepare the unification of the US-occupied zone and the Soviet-occupied zone, help Koreans not blemished by collaboration with Japan's militarist regime to establish an independent, democratic Korea, and effect rapid withdrawal of foreign troops, President Truman embraced a policy of non-cooperation in 1946 and leaned heavily on right-wing Koreans who were tainted by collaboration with the Japanese fascist miltarists. This departure from the democratic principles of the Roosevelt administration was due to the icy Cold War atmosphere that overshadowed the relations between the two major World War II allies when the Americans intervened covertly (since 1945) and openly (since 1946) in the Greek civil war – a war which saw the Soviet government stick to the promise given to Churchill that Greece was in the British zone of influence and that any support for the Greek Left should not be accorded by the Soviet Union. Despite the fact that the Soviet Union deserted the Left in Greece, the Greek civil war (1945-1949) contributed greatly to Truman's resolve that cooperation with the Soviet Union should be ended, that communism must be “contained,” and that an Iron Curtain was necessary. In line with the strategy of the Truman administration that obstructed all efforts to achieve rapid unification of Korea and end the military presence, “an interim legislature and interim government were established”in Seoul by the U.S. Military Government in 1946.(40) The two "interim" institutions were “headed by Kim Kyu-shik and Syngman Rhee respectively”and thus by men that the administration in Washington banked on.(41) Both institutions were illegal, however, as “these interim bodies lacked any [real and] independent authority”which was exercised by the American Military Government in Seoul, and because they also lacked “de jure sovereignty [of Korea], which was still held by the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea based in China [...].”(42) President Truman who was aware of

the fact that the Provisional Govrnment was still the only legal government

of Korea, chose, however, to ignore its legitimacy, partly “due

to [his concern] that it was communist-aligned.”(43)

[The Korean Communists were represented in this government-in-exile since

about 1920.]

* * *

Though subject to persecution, arrests and executions under the Japanese, the (internal rather than exiled) “Communist Party of Korea” was “still functioning in the southern areas” in September, 1945, and “worked under the name of Communist Party of South Korea” after the arrival of the American troops.(44) “The party [soon] merged with the New People's Party of South Korea and [...] [a] fraction of the People's Party of Korea” and this lead to the formation of "the Workers Party of South Korea on November 23, 1946.”(45) When the Workers Party of South Korea was “outlawed [by the American authorities] in the South, [...] the party organized a network of clandestine cells and was able to obtain a considerable following. It had around 360 000 party members. The clandestine trade union movement, the All Korea Labor Union was connected to the party.”(46) Being outlawed, thus kept from legal political participation, and reacting also to a wave of repression by the so-called interim government and its right-wing paramilitary units (formed by collaborators of the defunct colonial regime and victims of expropriations n the North who had sought refuge in the American zone), the South Korean Workers Party then decided in favor of insurrection. “In 1947 the party initiated armed guerrilla struggle. As the persecution of party intensified, large sections of the party leadership moved to Pyongyang.”(47) Meanwhile, the talks between the

Soviets and the Americans on unification went on without results and it

became clear that the American side wanted no unification and would bring

about so-called Korean independence in the South. Aware of this, and in

line with the sentiments felt by what must have been a majority of the

common people in the South, the Workers Party stepped up its organization

effort, being helped by the fact that it was the decisive political force

in the American zone that was “opposed

to the formation of a South Korean state.”(48)

Whereas no agreement between the US government and the Soviet Union regarding the process of securing unification could be reached, a majority of nations represented in the United Nations General Assembly voted in Nov. 1947, under U.S. pressure or influence, for a resolution that accorded independence to the former Japanese colony.(49)Quickly, a UN Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK) was established through Resolution 112 that was to oversee elections in all of Korea.(50) Acting unilaterally, the American occupation regime gave

the green light for elections in the American zone that were to result

in a South Korean assemblée constituante. The elections were

held in their zone in May 1948, under American control and the token

auspices of the UNTCOK.(51)

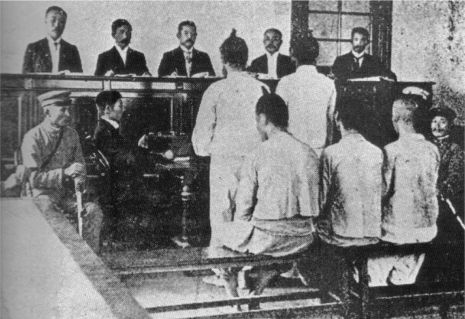

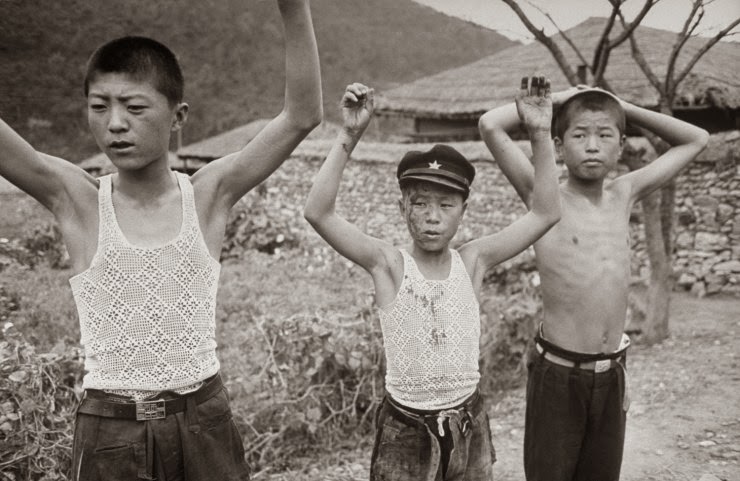

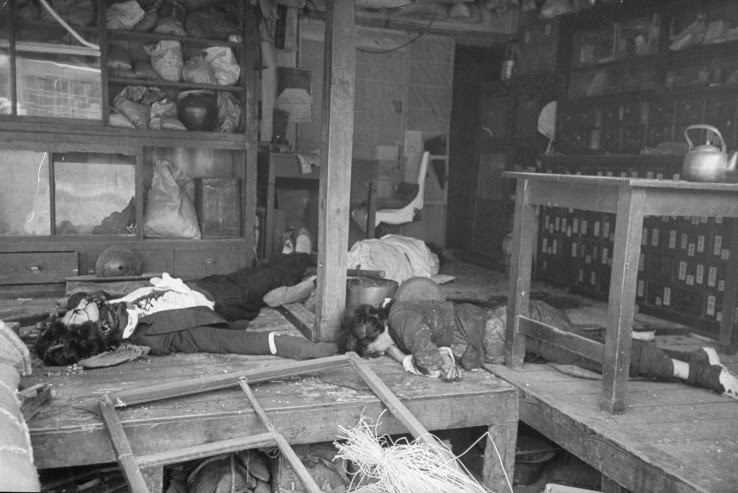

Prior to the elections, large protests against these elections took place in Seoul and other cities, because it was clear that carrying out the elections would cement the separation of North and South. The people in the South were aware that in "1946, the North [had] implemented land reforms by confiscating private property, Japanese and pro-Japanese owned facilities and factories, and placed them under state ownership."(52)This agenda and practice struck many in the South as very positive. In fact, "[d]emand for land reform in the South grew strong.”(53)And so did opposition to a strategy that was seen as unpatriotic, because it would cement separation between the North and the South. In February–March 1948, the outlawed South Korean Workers Party and the outlawed trade union linked in an effort to trigger "general strikes in opposition to the plans to create a separate South Korean state."(54) Then, in early April, the revolt on Cheju [Jeju] broke out, followed by other revolts, especially in the adjacent South Cholla province.(55) It was only under the impression of this series of revolts that flared up in the American occupation zone in 1948 that the U.S. Military Government finally opted in favor of a version of land reform in the South. Land reform “was eventually enacted in June 1949” and then carried out step by step.(56) Just as in Taiwan, where the Joint US-ROC commission adopted a land reform program, land reform in South Korea greatly profited those close to the regime.(57) The reform hurt the interests of the old landlord class because “Koreans with large landholdings were obliged to divest most of their land."(58) This stratum saw the compensation received as insufficient, and they were also embittered because new landlords with ties to the regime were created, and because expropriated land near the bigger cities was given cheaply to cronies of the regime who would then engage in lucrative urban property speculation, as the cities expanded. The reform had aimed at soothing a discontent class of small peasants without land of their own who resented the burden of exorbitant land rents. The reform seemed a partial success when “[a]pproximately 40 percent of total farm households became small landowners. However, because preemptive rights were given to people who had ties with landowners before liberation, many pro-Japanese groups obtained or retained properties” whereas many landless peasants and agricultural workers remained left out.(59) The readiness to tackle the issue of land reform in the American zone in 1948, two years after land reform had been carried out in the North, had not averted the revolt on the island of Cheju (a relatively large island in the utmost Southeast of the American zone).(60) The American magazine Newsweek (a mainstram publication) confirmed later that the uprising on Cheju happened above all because “Washington abandoned its commitment to organize all-Korea elections and instead announced a plan to hold balloting for a separate regime in the south […]”(61) Here, as elsewhere, “[l]abor-party leaders staged massive rallies to demand reunification.”(62) And here, as elsewhere, “[t]he police reacted, killing […] [peaceful] protesters.”(63) But the islanders were not ready to accept that. They “formed a 'people's army' and took to the hills. On April 3, 1948, rebels attacked police stations and government offices, killing an estimated 50 police.”(64)Then, ordered by the Americans, Rhee's regime reacted.(65) “The brutal suppression of the protests” by Syngman Rhee's national police and army which were both controlled in fact by the US Military Government resulted in some 60,000 victims on Cheju.(66) “American colonel Casteel who was the commander of [Ch]eju's security forces” oversaw “the destruction of many villages on the island,” and the execution of captured insurgents by the “extreme right-wing Northwest Youth” Corps and Rhee's “National Police.”(67) As in the case of other massacres in South Korea, US army

personnel took photos of executions carried out.(68)

For

them, it was clear that Cheju was a “red island”

and that the island population must be punished.(69)The

Americans ignored or did not care to give much consideration to the immediate

cause of the rebellion, the incidence that had triggered the bloody attacks

on Syngman Rhee's National Police (a right-wing corps formed largely by

former Japanese collaborators). Clearly the islanders, who had been staging

peaceful mass demonstrations against the planned partial elections, were

incensed because of the way the police was repressing such peaceful protests,

shooting and killing in at least one case a number of demonstrators. It

makes the fury of the attacks on police stations and the homes of policemen

understandable.(70)

While Cheju was suffering repression of its revolt since early April 1948, many other revolts broke out on the South Korean mainland, in the middle of the run-up period ahead of the election for the constituent assembly in May. The South Korean Labor Party [or “Workers Party of South Korea”], the main force on the Left that had been outlawed and persecuted in the South between 1945 and the UN decision to hold elections, decided to boycott the election. And this because, for one thing, the party did not want to lend legitimacy to a process that would separate the North and the South for what could be a long time, and (b) successful participation in the elections under conditions of harrassment and persecution was anyway unthinkable. Thus, the party supported the masses when they rose spontaneously, but in unplanned and uncoordinated fashion. Police stations and homes of policemen and Japanese collaborators were attacked by angry people. A number of collaborators, hated landlords, and others close to the Syngman Rhee-led interim government, but mostly policemen, were killed by the insurgents who took revenge for the suppression suffered under the Japanese colonial administration and by the security forces of Syngman Rhee. The crack-down that followed when the American army ferried replacements to the centers of revolt was terrible, especially in such towns as Jeosu [Yeosu] and Suncheon, in South Cholla province. (In Jeosu, the uprising had begun when army units from the region refused to depart for Cheju, to suppress the rebellion. The soldiers took control of the town. "The residents paraded through the town holding red flags. They restored the town people's committee, and tried and executed a number of police, officials, and landlords. [...] U.S. forces played a role in suppressing the rebellion: U.S. commanders planned and directed the military operations, U.S. military advisors accompanied all ROK units, and U.S. aircraft were used to transport troops." (71)

´ The partial elections opposed by many Southerners, because they would cement the partition of Korea, went ahead nonetheless – although in a climate of terror. Throughout the run-up period to the two elections held in May 1948 and July 1948 – the free, UN supervised election of the assembly that would adopt South Korea's constitution, and the even more decisive, free, UN supervised presidential election two months later – , National police and the military were hunting down left-wing activists, trade unionists, members of the peasant movement, and politicians. Assassinations, arrests, executions and torture were widespread. Armed revolts shook the country. In this atmosphere, the champion of General MacArthur's Military Occupation Government, Syngman Rhee, was elected without competition to serve in the assemblée constituante, called in Korean the Daehan Minguk Jahun (or National Assembly; literally Republic of Korea Constitution-making National Assembly).(72) And quite predictably, he was then also selected by the elected delegates as the speaker of the house.(73) A “Constitution of the Republic of Korea” was adopted by the members of the assemblée constituante on July 17, 1948.(74)

Three days later, Syngman Rhee was elected president of the Republic of Korea in a phony “presidential election” that brought him 92.3 percent of the vote – a result typical of dictatorships.(75) A necessary second candidate, Mr. Kim Gu, received 6.7% of the votes.(76) The Left, that was so strongly present in almost every town and village when the American troops had arrived, and that had enjoyed popular support in view of its active role as the most decisive force of anti-Japanese resistance in Korea itself, had remained underground; it had declared in advance that it would boycott the election. But in view of the wave of terror and bloody repression that swept across the country, it could not have fielded candidates anyway. On August 15, 1948 the long-term separation of Korea was sealed when the “Republic of Korea” was formally established in the American occupation zone and Syngman Rhee, who had been dominant in the Korean civil administration even in 1945-48, though of course unelected, began to serve as America's first “president” of that bloody and dictatorial republic.(77) “Soon after taking office, Rhee enacted laws that severely curtailed political dissent. Many leftist opponents were arrested”, if they had not been arrested in the days of April and May, 1948.(78) And those who weren't “killed”(79), were put under permanent surveillance and inducted into a militarily organized labor service euphemistically called the National Rehabilitation and Guidance League [or, for short, Bodo League], that was especially created for those suspected of leftist sympathies. Almost the entire number of members of this labor service (probably more than 100,000 – estimates range between 100,000 and 300,000; some claim 1,100,000 victims) were executed in 1950 on orders by Syngman Rhee when the war between the North and the South broke out.(80) Rhee's regime established a fascist-style “internal security force (headed by his right-hand man, Kim Chang-ryong)” in 1948 that went on to detain and torture “suspected communists” and those labelled North Korean agents.(81) “His government also [continued to] overs[ee] several massacres,” including the massacres on Cheju island that continued “from April 3, 1948 until May 1949”(82) according to one source, and until 1954, according to another source that includes later flare-ups and a number of peasant rebels who had succeeded to evade the forces engaged in the counter-insurgency campaign in the rugged terrain around Mount Halla until they were finally tracked down and massacred a year after the Korean War had ended. Recently, South Korea's Truth Commission reported new figures for the massacres on Jeju, after the chairperson of the commission was replaced by a Conservative government. The revised figures are not 60,000 or 30,000 but “14,373 victims, 86% at the hands of the security forces and 13.9% at the hands of communist rebels.”(83) “Newly declassified documents from the U.S. National Archive, and oral histories […] paint an unsavory picture of the prewar Seoul regime. The evidence supports a new interpretation of the Korean War – that hostilities actually started well before Pyongyang's armies blitzed southward on June 25, 1950.”(84) While this pre-history of the Korean war was tabooed by the mainstream media for many decades, the US news magazine Newsweek reported the respected “University of Chicago historian Bruce Cumings, a leading authority on the war's origins,” 50 years later as saying that [as the magazine quotes] “the [Korean] war began as a civil conflict in 1945 [...]”(85) From the moment the Americans had arrived in the south of the country, “the situation in Korea [had] steadily worsened. A civil war between communist and [so-called] nationalist forces in southern Korea resulted in thousands [and thousands] of people killed or wounded.”(86) As in Cheju, the victims were for the most part badly equipped leftists. They were murderd by a pseudo-nationalist right that had often served the Japanese already and that now served American geopolitical interests and enjoyed the support of the American military. It is clear by now that the Korean war began as a civil war. And when Northern troops crossed the 38th parallel in 1950, trying “to reunite the nation by force,”(87) this was obviously intended as a war of liberation that the North hoped to wage. They attempted to follow the example of the Left in China, and expected more insurrections by the common folks in the South – which failed to materialize because the repression in 1948 and 1949 had been so effective and so bloody, and because the executions of Leftists after the outbreak of the war reached almost genocidal proportions. That this conflict would not remain a fratricidal struggle among Koreans, but would immediately turn into a regular war, was inevitable because of the presence of the US army, the occupation force. These important forces, and then also their allies, backed by a UN mandate, got involved in what would have otherwise remained a civil war. Finally, on the side of the North, large numbers of Chinese (involuntary) “volunteers” were sent in to intervene. “Like Lafayette and his volonteers” – the Americans were informed. They came to aid the North when it was nearly vanquished, and this although Mao Zedong, the Chinese leader, was not keen at all to do so, as recently released messages between Mao and Stalin confirm.(88) But it had to happen when American troops reached the Yalu River, the Chinese-Korean border. Chinese security interests were at stake. In hindsight it is clear that it was the Cold War that

made it impossible for Koreans to solve the problem of national unity on

their own, either peacefully or through armed struggle. Both sides lost,

the people in the North and the people in the South. But the two rivals,

America and the Soviet Union, maintained the status quo on the Korean peninsula.

- William Crawford

NOTES (1) See for instance: Chang Ki Lee, The early revival movement in Korea (1903 - 1907) : a historical and systematic study. Zoetermeer : Boekencentrum, 2003. Cf.also: Andre Schmid, Korea between empires, 1895 - 1919. - New York NY : Columbia Univ. Press, 2002. (2) Cf. Kie-chung Pang, Landlords,

peasants and intellectuals in modern Korea

(3) Chang Ki Lee, The early revival movement in Korea (1903 - 1907) : a historical and systematic study. Ibidem. (4) Cf.Theresa Hyun, Writing women in Korea : translation and feminism in the colonial period. Honolulu, Hawaii : University of Hawai'i Press, 2004. (5) Dorothy Y. Ko, Women and Confucian cultures in premodern China, Korea, and Japan. Berkeley, CA : Univ. of California Press, 2003 (6) Allan R. Millet, Chapter 1, The Korean People. Missing in Action in the Misunderstood War, 1845-1954. especially the section entitled: “The People's War in South Korea, 1948-1950,” in: The Korean War in World History. Edited by William Stueck. Lexington KY : Univ. Press of Kentucky, 2004, pp.13ff.; the quote is from p. 17.-- See also Carter J. Eckert, Offspring of Empire: The Koch'Ang Kims and the Colonial Origins of Korean Capitalism, 1876-1945. Seattle : Univ. of Washington Press 1991, XV, 388 pp. ("Focusing his study on one powerful clan of Korean businessmen, Eckert examines the extent to which Japanese imperialism molded modern Korean capitalism."). - See also: Dennis L. MacNamara, Trade and transformation in Korea : 1876 - 1945. - Boulder, Colo. : Westview Press, 1996. On Japanese colonial policies and the beginnings of dependent capitalist development in Korea, see: Kenji Kimura, Japanese settler colonialism and capitalism in Japan : advancing into Korea, settling down, and returning to Japan, 1905 - 1950. Cambridge, MA : Harvard Univ., Edwin O. Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies, 2002 and also Alexis Dudden, Japan's colonization of Korea : discourse and power. Honolulu : Univ. of Hawai'i Press, 2005 [Reprint]. Cf. also: Gi-Wook Shin, Colonial modernity in Korea. - Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard Univ. Asia Center, 1999. (7) Hyun-Ock Cho, Soziale Bewegung und Modernisierung in Korea. Hamburg : Kovac, 1999. (8) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syngman_Rhee) (9) In fact, there existed a certain continuity between the struggle of the diverse foci of the 'righteous army' against the Japanese in Korea during the 1920s, and the resumed struggle that was to lead to the liberation of many parts of Korea in early 1945, ahead of the arrival of US troops. After the defeat of the original 'righteous army,' “[m]any of the surviving guerrilla [members] […] [had] fled to Manchuria and Siberia [which was part of the Soviet Union] and carried on their fight.” (N.N.,”Righteous Army,” in: Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Righteous_army) (10) It was, "in fact, organized as the Korean Section, Russian Communist Party, in Irkutsk, Siberia in January 1918." - Allan R. Millet, ibidem, p. 17. (11) Allan R. Millet, ibidem, p. 17. (12) Allan R. Millet, ibidem, p. 17. (13) Allan R.Millet, ibidem, p. 17. - The remaining Shanghai faction of Korean communist party "took on a new life," however, by becoming a "part of the Chinese Communist Party [....]." Millet emphasizes that it produced two noteworthy leaders, "Kim Tu-bong, a political organizer, and Kim Mu-chong, a guerrilla leader in the March First Movement. The latter, a trained artillery officer, joined the Eighth Route Army and survived the Long March in a unit lead by Peng Dehuai, future commander of the Chinese expeditionary force in Korea. The two Kims and other dedicated Korean revolutionaries [later] formed the Yanan faction [of the Korean communists], which still maintained ties to the Provisional Government through Yo Un-hyong, and which participated with skill and conviction in the war against Japan after 1937." (Millet, ibidem, p.17f.) (14) Allan R. Millet, ibidem, p.18. (15) Allan R. Millet, ibidem, p.18. (16) Allan R. Millet, ibidem, p.18. (17) Allan R. Millet, ibidem, p.18. (18) Allan R. Millet, ibidem, p.17. (19) “Its commandant was General Ji Cheong-cheon, with General Lee Bum Suk, a hero of the Battle of Cheongsanri and future prime minister of South Korea as the Chief of Staff.” (N.N. , “Korean Liberation Army,” in: Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Korean_Liberation_Army) (20) When Shanghai was occupied by the Japanese army, the Provisional Government was relocated to "Chongqing (then spelt Chungking)”. - N.N., “Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea,” in: Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Provisional_Government_of_the_Republic_of_Korea (21) N.N. , “Korean Liberation Army,” in: Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Korean_Liberation_Army (22) Concerning the Korean

population in dong bei (ex-Manchukuo), see for instance: Eckart

Dege, Die koreanische Minderheit in der VR China : [Vortrag gehalten

auf der Tagung des IfSF "Korea vor der Wiedervereinigung?!"],

(23) N.N., “American troops

arrive in Korea to partition the country,” in: “This Day in History”

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/american-troops-arrive-in-korea-to-partition

(24) N.N. , “Korean Liberation Army,” in: Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Korean_Liberation_Army (25) N.N. , “Korean Liberation Army,” in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (26) N.N., “Korean Liberation Army,” in: Wikipedia, ibidem. - Regarding the administrative policies and measures of the US Military Government in Korea see: Bonnie Bongwan Cho Oh, Korea under the American military government, 1945-1948. Westport, CT : Praeger, 2002. (27) N.N., “Timeline of Korean History” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_Korean_history (28) N.N., “Timeline of Korean History”, ibidem. (29) N.N., “Timeline of Korean History”, ibidem. (30) Newsweek Staff, “Ghosts

of Cheju,” in: Newsweek, June 19, 2000. http://www.newsweek.com/ghosts-cheju-160665

(31) N.N., "History of South Korea," in: Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_South_Korea. - See also: Bonnie Bongwan Cho Oh, Korea under the American military government, 1945-1948. Westport, CT : Praeger, 2002. (32) Newsweek Staff, “Ghosts of Cheju,” in: Newsweek, June 19, 2000. http://www.newsweek.com/ghosts-cheju-160665 (33) Newsweek Staff, “Ghosts of Cheju,” ibidem. (34) While in Washington, Syngman Rhee had been named chairman of the “foreign relations department” by the so-called provisional government of Korea in Chongqing. (N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia,http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syngman_Rhee). - See also the entry "Syngman Rhee," in: Frank J. Coppa (ed.), Encyclopedia of modern dictators: from Napoleon to the present. New York NY : Peter Lang, 2006, p. 256. (35) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syngman_Rhee. See also: Bruce Cummings, The Korean War: a History. New York NY : Modern Library / Random House Publishing Group, 2010, p. 106. (36) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syngman_Rhee. See also: Bruce Cummings, The Korean War: a History. New York NY : Modern Library / Random House Publishing Group, 2010, p. 106. (37) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syngman_Rhee) (38) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,”ibidem. (39) N.N., "History of South

Korea," in: Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_South_Korea

(40) N.N., "History of South Korea," in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (41) N.N. "History of South Korea," in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (42) N.N. "History of South Korea," in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (43) N.N. "History of South Korea," in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (44) N.N. "Communism in Korea," in: Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Communism_in_Korea (45) N.N. "Communism in Korea," in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (46) N.N. "Communism in Korea," in: Wikipedia, ibidem. The figure 360,000 is also given in: ´Chong-Sik Lee, "Politics in North Korea: Pre-Korean War Stage," in: The China Quarterly, No. 14 (April-June 1963), pp.3-16. (47) N.N. "Communism in Korea," in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (48) N.N. "Communism in Korea," in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (49) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” Ibidem. (50) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,”Ibidem. (51) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” ibidem. (52) N.N., "History of South Korea," in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (53) N.N., "History of South Korea," in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (54) N.N. "Communism in Korea," in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (55) N.N.,

“Jeju Uprising,” in: Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeju_Uprising).

On the revolt on Cheju Island [Cheju-do], see: John Roscoe Merrill, "The

Cheju-do Rebellion," in: Journal of Korean Studies, Vol. 2,

No. 1 (Jan. 1, 1980), pp. 139-197. Republished as electronic

file, Seattle : Center for Korea Studies, University of Washington,

March 30, 2011.

(56) N.N., "History of South Korea," in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (57) In Taiwan, "[t]he land reform proceeded in three stages, First, in April 1949, farm rents were limited to a maximum of 37.5 percent of the total annual main-crop yield as approved by specially appointed Rent Campaign Committees. In stage two, lasting from 1948 to 1951, public farm land, which had formerly belonged to the Japanese government or individuals and had been confiscated by the Nationalists, was leased or sold to tenant farmers. By 1953, 63,000 chiahad been sold. The third stage, "land to the tiller," was more complex. First, the land was classified by owners and graded for quality. The Land to the Tiller Act of 1953 set an upper limit of three chia of seventh- to twelfth-grade paddy field for landlords to retain; all land over three chia was subject to compulsory purchase by the government for resale to the present cultivators. Landlords were compensated 70 percent with land bonds in kind (rice for paddy land, sweet potatoes for dry land) and 30 percent with shares of stock in for government enterprises earmarked to be transferred to private owenership - Taiwan Cement, Taiwan Paper and Pulp, Taiwan Agriculture and Forestry, and Taiwan Industry and Mining. In all, about one-quarter of Taiwan's cultivated land was affected [...] Land cultivated by owner-cultivators increased from 50.5 percent of the total in 1949 to 75.4 percent in 1953. Tenant-culivated land fell from 41.8 percent to 16.3 percent over the same period [...] Owner-farmers increased from 33 percent of the total in 1948 to 57 percent in 1953; part owners declined from 24 percent to 22 percent. Tenant farmers fell from 36 percent to 15 percent [...] Small landowning families became the dominant force inTaiwan's countryside." (Thomas B. Gold, State and Society in the Taiwan Miracle, Armonk NY: M.E. Sharpe/An East Gate Book 986, pp.65f.) [1 chia = 0.97 hectares = 2.4 acres] - "[S]ince the beginning of land reform, Taiwanese landlords have lost onterest in politics [...]" (Hung-chao Tai, Land Reform and Politics: A Comparative Analysis. Berekely CA : Univ. of Calif. Press 1974, p.335) - In the context of land reform and suburban land speculation, see also: Younghoon Ro, Land taxation in Korea : a critical review of current policies and suggestions for future policy direction. Seoul, 1996 (58)

N.N., "History of South Korea," in: Wikipedia, ibidem., also: N.N., "First

Republic of South Korea," in: Wikipedia

(59) N.N., "History of South Korea," in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (60) N.N., "Jeju Uprising," in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (61) Newsweek Staff, “Ghosts of Cheju,” in: Newsweek, June 19, 2000. http://www.newsweek.com/ghosts-cheju-160665 (62) Newsweek Staff, “Ghosts of Cheju,” ibidem. (63) Newsweek Staff, “Ghosts of Cheju,” ibidem. – According to another source, the demonstration during which police shot at and killed Jeju islanders, though happening in an atmosphere of opposition against the planned partial elections in the South, was “a demonstration commemorating the Korean struggle against Japanese rule.” (N.N., “Jeju Uprising,” in: Wikpedia, ibidem) Such a demonstration could hardly please the police, as police units had largely been formed by collaborators who had already served under the Japanese colonial authorities. This is comparable to the situation in West Germany's American and British occupation zones where the police and judges were mostly personnel that had served in the same function under the Nazi regime. In Bavaria (American zone), Klaus Barbie, the Gestapo boss in a major French city, Lyon, who personnaly murdered and tortured Jean Moulin, a famous leader of the French resistance, was released from jail by the Americans and employed by them “to hunt down Communists” in South Germany (as the liberal Suddeutsche Zeitung reported many decades later). (64) Newsweek Staff, “Ghosts of Cheju,” ibidem. (65) The US news magazine Newsweek reported many years later, based on official document available due to the recent Freedom of Information Act, that the “South Korean authorities” entrusted by the Military Government with suppressing the revolt, “waged a scorched-earth campaign” on the island. Since the inception of the campaign and “[o]ver the next year, the soldiers nurned hundreds of “red villages” and raped and tortured countless islanders, eventually killing as many as 60,000 people – one fifth of Cheju's population.” Newsweek, June 19, 2000. http://www.newsweek.com/ghosts-cheju-160665) (66) Newsweek Staff, “Ghosts of Cheju,” ibidem. (67) The Americans later called the complete destruction of Jungsangan village, the biggest tragedy of the events, a "successful operation". (N.N., “Jeju Uprising,” ibidem, see also: http://www.jeju43.go.kr/sub/catalog.php?CatNo=27) (68) “The Americans documented the brutality but never intervened.” (Newsweek Staff, “Ghosts of Cheju,” in: Newsweek, June 19, 2000. http://www.newsweek.com/ghosts-cheju-160665) (69) N.N., “Jeju Uprising,” in: Wikipedia, ibidem.; also: http://terms.naver.com/entry.nhn?docId=1141380&cid=40942&categoryId=31778 (70) Cf. Newsweek Staff, “Ghosts of Cheju,” ibidem. (71) N.N., "Yeosu–Suncheon Rebellion," in: Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yeosu-Suncheon_Rebellion (72)

N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia,

(73) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (74) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (75) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia, ibidem. - It is for good reason that we find an entry entitled "Syngman Rhee," in: Frank J. Coppa (ed.), Encyclopedia of modern dictators: from Napoleon to the present. New York NY : Peter Lang, 2006, p. 256. Though adored in the mainstream press of the West during the early 1950s as a hero of Korean democracy, Rhee was undoubtedly a dicator during all or most of the time he served as president of the Republic of Korea (ROK). On the other hand, the dictatorial character of the government in the North cannot be put in doubt either. The Democratic People's Republic of Korea openly defines itself as a "dictatorship of the proletariate." Critics say that it is more of a dictatorship of a politbureau that is bossing the "proletariate." It requires socio-historic research to determine when and to what extent the party and its leadership experienced the loss of voluntary loyalty and support by those parts of the population that rallied behind the workers' party in the mid and late 1940s, both in North and South Korea. As far as the South is concerned, it is clear that in recent years other political tendencies than the Communist Party have received the backing of the progressive and left-leaning parts of the population. (76) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (77) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (78) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (79) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (80)

The term labor service describes the fact that those inducted were

compelled to do forced labor, instead of being imprisoned. The official

term was bodo league. "In June 1949, the South Korean government

accused independence activists" to be communists. “In 1950, just before

the outbreak of the Korean War, [...] Syngman Rhee, had about 30,000

alleged communists imprisoned; he also had about 300,000 suspected [communist]

sympathizers or [...] political opponents enrolled in an official 're-education'

movement known as the Bodo League (or National Rehabilitation

and Guidance League, National Guard Alliance, National Guidance

Alliance, National Bodo League, Bodo Yeonmaeng, Gukmin

Bodo Ryeonmaeng, [...]) on the pretext of protecting them from execution.

A lot of [the compulsory] Bodo League members [subjected to work schedules

combined with military discipline] were civilians who had no connection

with communism or communists. A lot of them were [...] listed [i]n [the]

Bodo League because [...] government officials were pressed by their superiors

to make the number larger. Non-communist sympathizers or political opponents

of Rhee were also forced into the Bodo League to fill [...] quotas. [...]

According to Kim Mansik, who was a military police superior officer, President

Syngman Rhee ordered the execution of people related to either the Bodo

League or the South Korean Workers Party on 27 June 1950, the first massacre

was started one day later in Hoengseong, Gangwon-do on 28 June. Retreating

South Korean forces and anti communist groups executed the alleged-communist

prisoners, along with many of the Bodo League members [during 1950]. The

executions were performed without any trials or sentencing. United States

official documents show American officers witnessed and photographed the

massacre. In one case a US officer is known to have sanctioned the killing

of political prisoners so that they would not fall into enemy hands." (N.N.,

"Bodo League Massacre," in: Wikipedia

(81) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (82) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia, ibidem. (83) N.N., “Syngman Rhee,” in: Wikipedia, ibidem (84) Newsweek Staff, “Ghosts of Cheju,” ibidem. (85) Newsweek Staff, “Ghosts of Cheju,” ibidem. (86) N.N.,

“American troops arrive in Korea to partition the country,” in: “This

Day in History”

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/american-troops-arrive-in-korea-to-partition

(87)

N.N., “American troops arrive in Korea to partition the country,”

ibidem. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Republic_of_South_Korea.

(88) See

telegram

to Stalin (from Beijing) reporting Mao Zedong's answer to Stalin's

suggestion that China should aid the North Koreans, 3. Oct 1950

Go back to Art

in Society # 14, Contents

*

|

.

|