Internal Problems and Outside Meddling.

Where Will It Lead?

Like other countries of post-Cold War Eastern and Southeastern

Europe, Ukraine is a country haunted by internal problems, polarization,

poverty of the many who had such great expectations, unscrupulous enrichment

of the few, a deep and unsolved economic crisis, and conflicting nationalisms.

It is also plagued by outside meddling. We are usually told it's the Russian

government that interfers in their internal affairs. Yes, they do. But

are they the only ones? And who acts, and who reacts? As so often, it helps

to look back, not just to the events on Maidan Square in early 2014, but

perhaps at least to 2004, if not a lot deeper into the country's history.

In December, 2004, Victor Yushchenko, the election candidate

favored in the Western parts of Ukraine, “said […] that attempts to make

Russian the country's second official language ha[s] become a political

issue.” (1) He was against Russian as

a second official language. The statement as such was indicative of the

rift between the West and the East of the country, and of the intolerance

among Western Ukrainian nationalists. It was an intolerance nourished by

resentment and traumas. Wrong as it was and still is, it is also understandable.

In order to understand it, one has to look for its roots.

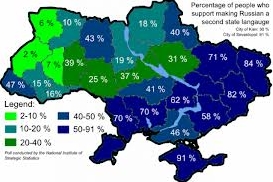

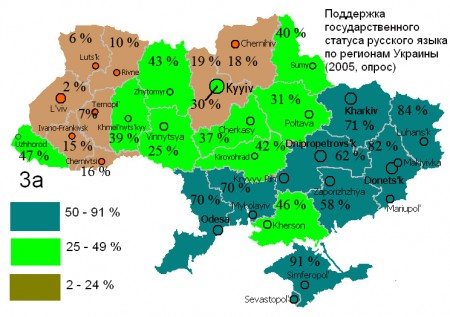

Percentage of people who support making Russian an official second

language (2005)

Native speakers of Russian

native Russian native speakers

speakers (%) of Ukrainian (%)

(1) Charkov

. 44.3

53.8

(2) Lugansk

68.8

30.0

(3) Donetsk

74.9

24.1

(4) Dnjepropetrovsk 32.0

67.0

(5) Zaporozhe

48.2

50.2

(6) Cherson

24.9

73.2

(7) Mikolaev

29.3

69.2

(8) Odessa

41.9

46.3

Source: http://www.liga.net/infografica/104824_novyy-vavilon-karta-regionalnykh-yazykov-ukrainy.htm

In the period following the attack of Nazi Germany on

the Soviet Union, then a U.S. ally, many Western Ukrainians had welcomed

the Nazi invaders, lining the streets of small towns and villages, flowers

in their hands, as Nazi wehrmacht tanks passed through. It was a view that

resembled the welcome of U.S. troops in small towns and villages of Normandy

after the invasion. Quite a few nationalist young Western Ukrainians joined

an auxiliary army corps in 1941 that fought side by side with the Nazi

wehrmacht army against the Soviet Union. Others became guards in Nazi concentration

camps, taking part in the genocidal murder of Poles, Jews, and White Russians.

Still others took part in anti-partisan actions and the rounding up of

Jews carried out by the infamous Nazi German sonderpolizei (i.e., special

police) units. The Ukrainian nationalists hoped of course that Hitler

Germany would favor the establishment of an independent Ukrainian puppet

regime, similar to the one that existed in Slovakia. When this was not

forthcoming, certain Ukrainian nationalists turned against the Germans

and the Russians. Their hero and leader was Bandera. He is still admired

and venerated by many Western Ukrainian nationalists.

In Eastern and South Eastern Ukraine, the situation was

different. Many Russians settled in these areas. The industrialization

effort in the Donbas region had brought a large influx of workers

from the entire Soviet Union, something that marginalized the kind of Ukrainian

nationalism that led to collaboration in the Western districts. And the

port cities at the Black Sea coast had always been more cosmopolitan than

nationalist in the 19th and 20th century. When the country was attacked

by Nazi Germany, these people, regardless of their approval or disapproval

of Stalin's pre-war policies, proved ready to resist the attack. The viciousness

of both the attack itself, the “special measures” taken in Nazi-occupied

territories, and the scorched earth tactics of retreating wehrmacht troops

all bolstered a heroic anti-fascist spirit among those who resisted Hitler

Germany. The memories of the sacrifices made are kept alive in oral

history, in the narratives transmitted among family members, and in cultural

life, generally. In the post-World War II period, heroic monuments commemorating

the sacrifices made by soldiers of the Red Army and the anti-Nazi partisans

were erected in many parts of the Soviet Union, and thus also in Ukrainian

towns. Today, Western Ukrainian nationalists have begun to tear them down,

causing suspicion and anger among other Ukrainian citizens, mainly in the

Eastern parts of the country.

If in the Eastern areas, identification with the victory

over Nazi Germany is still prevalent, in the West of the country, the opposite

is largely true. Defeats, not victory color the collective memory. Anti-Russian

resentment is strong. In 1945, the Nazi collaborators continued a partisan

struggle against the Soviet authorities that was supported by

the C.I.A. since at least 1947, and well into the 1950s, when the

guerilla was finally defeated. In these early post-war years of the late

1940s and early '50s, the Western Ukrainian guerilla murdered a considerable

number of directors of collective farms, of Communist party secretaries,

village and small town mayors and so on. In other words, the right-wing

nationalists – supported covertly by the U.S. government –

murdered those Western Ukrainians who threw their lot with the authorities,

either out of conviction or due to careerism, or because they were compelled

by the Soviet government to accept such posts.

This map shows the situation after the peace treaty signed in

Brest-Litovsk. Russia is depicted in green, Austria-Hungary, the German

empire and their Bulgarian ally are shown in blue. Ukraine had been created

as a de facto ptotectorate of the Germans, governed by a "hetman" and controlled

by the German imperial army. French troops occupied Crimea.

It is clear that this historic experience had traumatic

effects. But many historians in search of the roots of Western Ukrainian

traumas (and the resulting extreme nationalism) also refer to the big famine

that cost so many lives in Ukraine in the early 1930s. Actually, there

were at least two, if not three terrible periods of famine. In 1917-1918,

the occupying German forces bought or confiscated large quantities of food

which was then exported in order to feed the starving German population;

this created a food shortage in Ukraine. The civil war between Czarist

troops in Southern Ukraine, Machnoist anarchist troops and Bolshevik troops

ravaged the country and made sowing and harvesting next to impossible in

1919-1921. It brought about severe regional starvation. And thus, in the

aftermath of the civil war, bands of orphaned, hungry children roamed the

country, in search of food. Workers in Western and Central Europe collected

money in solidarity, hoping to aid the starving.

When the Germans withdrew, "White" troops commanded by Czarist

generals took control of Ukraine.

The area affected in 1919 by the anarchist insurrection, led

by Nestor Machno, is shaded darkly.

Odessa and Sevastopol were still occupied by French intervention

forces that supported the Czarist or "White" troops.

In March, 1920, the "White" troops controlled only a remnant

of Ukraine in the South, and the Machnoist units had also been defeated

by the Red Army.

During the so-called NEP period the situation improved

but the government in Moscow noticed also negative consequences. When Stalin's

government ordered collectivization of the agricultural sector to be carried

out in the early 1930s – a nonsensical policy, in many respect because

it disregarded traditions of mutual help and replaced the “peasant way”

of cooperating by a bureaucratic way that favored “industrialized” American

production methods –, a producers' strike resulted, mainly among middle

and rich farmers.

It may seem strange today that there existed rich and

middle farmers after the October Revolution, but the revolution had not

expropriated them and the farmer's markets allowed by the New Economic

Policy had improved their lot. In German-speaking areas along the Dnjepr,

for instance among German-speaking Mennonites in the Zaporozhe area, affluent

farmers were predominant. It was possible that a wealthy farmer, who had

profited from NEP policies, owned two modern tractors by 1928. In

the German-speaking villages, work was done mainly by family members, and

families were usually large. But the lowly work was delegated to Russian

or Ukrainian servants. Paternalist relations between master and day laborer

had even entailed inhuman practices under Czarist rule and during the civil

war. Agricultural workers were often beaten or flogged when talking back

or proving too undisciplined, in the opinion of their employers. During

the revolution and the civil war, a considerable number of the village

poor had turned to the anarchists, sometimes also to the Bolsheviks, and

in the towns, many industrial workers had turned to the Bolsheviks while

the educated (with the exception of quite a few Jewish intellectuals and

a few other progressives), the middle class, the merchants and so on tended

to oppose them. Thus, by 1930, the Soviet authorities did not find a united

front of opposition to their collectivization measures in Ukrainian villages.

Class antagonism and animosities that dated back to earlier periods continued

to exist and this meant that the authorities found those, locally, they

could lean on.

It was clear to people like Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin

that the military victory of the Bolsheviks in the civil war and the fact

that they rose to power, politically, did not quell anti-revolutionary

sentiment among those who had opposed them. Under Stalin, and perhaps even

before he took absolute control, the political apparatus created to repress

such dissidents developed its own dynamics, however, similar in some respects

to the way in which internal security concerns are leading today to a continually

expanding security state. In the 1930s, the resistance to collectivization,

put up mainly by rich and middle farmers in Ukraine – which was the bread

basket of Russia and which had been an exporter of food under the Czars

(when lucrative exports had periodically produced high bread prices and

widespread malnutrition among the poor) – could only be passive resistance.

The farmers who were forced into a collective farm (a so-called kolkhoz)

frequently worked carelessly; in many cases, they planted and harvested

just enough to feed themselves. Surplus grain was left to rot in the rain

rather than sheltered from the weather in barns. When the amount of harvested

grain proved abnormally small, those who had “sabotaged” things in the

opinion of the government were arrested, taken away, and presumably shot.

Those who remained behind in the village where compelled to give all the

food resources kept for themselves, in order to fill the normal quotas.

The regime had no other way. The workers in the cities – their main power

base – had to be fed. The cities depended on food from Ukraine. With a

disastrous harvest in Ukraine, their rations had to be cut, too. The villages

that had refused to produce a normal output because they resented a form

of cooperation ordered bureaucratically from above, paid a terrible price.

Many died of starvation. But urbanites were exposed to malnutrition, as

well. This famine is still part of the historic legacy that separates Ukrainians

with rural roots from “the authorities” in Moscow – and from Russian-speaking

miners and steelworkers (or today, ex-miners and former steelworkers) in

the Eastern Ukrainian Donbas region. It was the miners and steelworkers

of the Donbas who had received better rations during the famine, because

of their strategic importance for the country.

In 2004, the International Herald Tribune was preferring

a mild understatement when its journalist wrote that political resistance,

by nationalist West Ukrainian politicians, especially by Viktor Yushchenko,

to the introduction of Russian as a second official language was “likely

to anger voters in Russian-speaking Eastern parts of the country, most

of whom support his opponent” – presidential candidate Viktor Yanukovich.(2)

Russian had of course functioned as an official language

in Ukraine during the Soviet period. When Yeltsin agreed that a referendum

on the question of independence should be held, it was the Eastern part

of Ukraine that had featured a considerable number of voters who were in

favor of remaining a part of Russia. But those who say that their mother

tongue is Russian form only about one fifth of the population (while

Ukrainian citizens with Russian roots, according to other estimates that

are based on a number of socio-culturally relevant factors, account for

perhaps 30 per cent), and thus the forces of opposition to Ukrainian independence

were of course defeated.

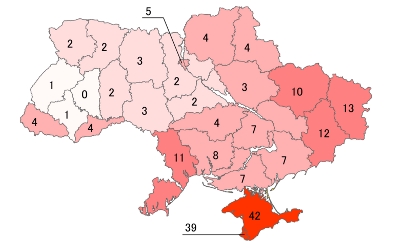

The referendum on separation from the former

Soviet Union, held in 1991. The dark red area featured an especially large

percentage of voters who opposed separation.

Nationalist sentiment in those days that saw Ukraine gain

independence ran high, and the new constitution that was adopted immediately

after Ukraine split with Russia stipulated that “Ukrainian” should be “constitutionally

protected as the language of government, the police and the military, universities,

and most schools.”(3) While “[m]ost children

are bilingual,” this will not necessarily stay so if Russian continues

to be suppressed as a means of communication that can be used in official

business, such as talking to a policeman or filing a tax report. Many native

speakers of Russians “fear […] promotion of Ukrainian at the expense of

Russian” because it may be “leading to discrimination in employment and

other area.” (4)

All of this must be seen in the context of the global

economic crisis and the grave economic difficulties that Ukraine seems

unable to cope with while its political pseudo-elite and its rapacious

post-Socialist tycoons continue to enrich themselves, in ways very

much like those noted in Bulgaria, Romania, Russia, and even to some extent

in Poland and Slovakia.

Socio-cultural conflicts rooted in different historic

experiences that give rise to different views of history and thus, different

“identities” and loyalties, are a distinct feature of Ukrainian reality.

In the West, the Roman Catholic church was strongly present in former Galicia,

a province – until 1918 – of Austria-Hungary. Today,

most Ukrainians say that they are atheists or that they do not belong to

a church. Only 1.7 per cent of the population of Ukraine belong to the

Roman Catholic church. Then, of course, there is also the Greek Catholic

Church – it, too, is loyal to the pope in Rome. 14.7 percent

of the population profess adherence to this section of Catholicism. If

both figures add up to only 16.4 per cent who are Catholics, we must not

forget that the socio-cultural imprint the church left in many Ukrainians

for generations, lingers on in the minds of more recent generations who

do not profess a formal adherence.

In view of the historic role of Constantinopolis and Kiev,

the Orthodox variety of Christianity is of course more strongly present

in much of the country. 38 per cent of the population belong to the section

of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church that is headed by the patriarch in Kiev,

and 29.4 per cent are indirectly members of the Russian Orthodox Church,

as they follow the patriarch in Moscow, even though they formally constitute

a section of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

The regional distribution of believers is obvious. Catholics

are overwhelmingly present in the Western part of the country that belonged

to Poland, then to the Austrian empire and then again to Poland. The believers

who look to Moscow are heavily present in areas with a considerable presence

of native speakers of Russian.

A socio-cultural East-West contrast exists in another

sense, as well. The West, despite some urban centers, is more rural. The

East was and to some extent still is a mining and steel-making region.

The Ruthenes, West Ukrainian mountain people of the Carpathian

region, were inhabitants of a particularly poor part of the country – and

famous for becoming soldiers in the Austrian army. Like so many poor people

from the backcountry, whether in the U.S. or the UK, they saw their

chance of advancement or of earning at least a living for the family

back home, in military service. Lack of education and the influence

of the Catholic church made them conservative; in 1848, Ruthenian army

units bloodily suppressed the democratic revolution of the Poles. In 1918,

the West Ukrainians in former Galicia coveted a republic of their own:

it was an understandable nationalist endeavour of small people who were

ready to emancipate themselves from the Austrian yoke. Their short-lived

National Republic of Western Ukraine was on difficult terms with the People's

Republic of Ukraine to the East of it that was governed briefly by anti-Bolshevist

Ukrainian social democrats. (This people's republic had no links to Bolsheviks

in Russia or Marxist revolutionaries in the Hungarian Soviet Republic.)

The National Republic of Ukraine was attacked by the young Polish Republic,

however, and defeated in bloody battle. These West Ukrainians, just escaped

from Austrian rule, were now ruled by Poland.

In a part of former Galicia, a National Republic of Western Ukraine

had been formed in the wake of the collapse of Czarist Russia. The territory

of this short-lived republic was annected by Poland on July 18, 1919. A

People's Republic of Ukraine existed in Western Ukraine just East of this

National Republic, It was subjected by the Red Army. The Hungarian Soviet

Republic formed at the end of WWI existed until August 1, 1919.

As Polish soldiers, they were forced to join the attack

of Britain, Japan, and Poland on the young Soviet Russian republic. When

the Soviet Red Army counterattacked, they too suffered losses. When the

Poles won in the end and peace between Poland and Soviet Russia was concluded,

they became part of a vast Poland, a country full of historic pride after

having recovered Ukrainian and White Russian lands once ruled by Lithuanian

grand-dukes and Polish kings. It was an authoritarian and repressive republic,

dominated by general Pilsudski until 1936. The West Ukrainians in

what was now Polish Galicia remained Polish citizens until the moment they

were occupied by the Red Army, as a direct result of the non-aggression

treaty concluded by Ribbentrop and Molotov – an agreement reached between

Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that gave the latter country a brief

respite, until 1941, while sacrificing Poland. When Poland was divided

up, Western Ukrainians at home in Galicia joined the rest of Ukraine again,

under Soviet rule.

Ukraine in 1920

Galicia, as it were, had its own traditions. The Austro-Hungarian

monarchy prided itself of being more advanced industrially and in other

respects than Czarist Russia. There existed a more civil form of what we

would call today the rule of law than was the case under the Russian

czars. The civil service and the education system were fairly advanced.

If Czarist- controlled Ukraine experienced pogroms intermittently, in Austria-Hungaria

law and order was maintained and anti-semitism took on more subtle forms

between 1850 and 1918.

Of course, Jewish American writers with roots in Galicia,

like Isaac Bashevis Singer, have kindled our awareness of the “stedl” –

the Jewish parts of town that were a characteristic feature of many cities

in Austrian-ruled Galicia. The cities in Galicia were – if it is allowed

to use a modern term – in some way or sense multi-national cities.

There were Slovaks, Poles, Jews, Germans, Romanians, who had to get along

and who got along peacefully in Ukrainian cities of Austrian-ruled Galicia.

In the parts of Ukraine ruled by Czarist Russia, a similar mixture of populations

could be observed; in that respect, they were not very different. In the

sea ports, one could even find a considerable number of Greeks. The merchant

class, or commercial bourgeoisie, tended to be in a way cosmopolitian in

their outlook, contacts, commerical relations, and even, perhaps, in their

manners. And this despite definite national cultural trends and the stubborn

use of their maternal language, side by side with the official language

and other languages that proved useful to those accustomed to do business.

In comparison, the Ukrainian villagers and the servants of Ukrainian stock

seemed almost deficient. Like any exploited, subjected class, they were

robbed of the chance to unfold their human potentialities. It was this

deprivation that produced a chip on their shoulder while the grip, that

the Catholic church (in its Roman or Greek form) had on these “simple”

minds, contributed to their deep-rooted anti-Judaism, very much in the

same way as in Poland and in rural and small-town-Germany.

Ukrainian writers like Jura Soyfer, who was born in Charkov

[Kharkov; in Ukrainian: Kharkiv] in 1912, had Hungarian, Jewish, Polish

and German friends.(5) This was also

typical of Jewish intellectuals in other Ukrainian cities, especially in

important cities like Lvov (known as Lemberg, under Austrian rule). Soyfer's

father was a Jewish industrialist in Charkov. This was also not untypical.

In cities like Lvov [Lviv, or Lemberg], Charkov – or Lodz (a textile-industrial

city in Poland) – , Jews were either part of the industrial bourgeoisie,

bankers, merchants, or they were clerks, accountants, engineers, etc.,

while in the villages, they tended to be roaming peddlers, local hawkers

or shop owners, money lenders, horse dealers, and so on. Practically none

were likely to be farmers, peasants, blacksmiths... The poor among them,

and there were many, would have daughters who worked as maids, as household

helps, usually in the mansions of the Jewish bourgeoisie, and sometimes

in textile factories owned by Jews, while boys of poor families might get

a badly paid job in a small shop or office. Though the class structure

was reflected in the Jewish ambiente of Eastern European towns, the concrete

form of this existence was different from that of many Ukrainians. This

separate existence – upheld by anti-judaist religious sentiments,

by the historic existence of segregated quarters (“ghettos”), by

legally prescribed and also informal discrimination – perpetuated

stereotypes of the Jew as the Other, including such cliché-ridden

ideas as “the Jewish usurer” and “the clever Jewish businessman”:

widespread, popular views held by members of all classes who disregarded

both the proletarian reality of many poor Jews (a majority) and the

reality of emerging financial capitalist structures (which were by no means

“Jewish” in character, as Jewish bankers played a role that was not different

from the role played in this sector by Germans, Greeks, Frenchmen, Russians

and so on). The concept of usury was appropriate to a medieval reality,

and it vibrated with Catholic misgivings and preconceptions that condemned

interest-taking while supporting the inequality of a class society. But

as a simple category, linked to a “holy” text that forbade interest-taking,

it offered an easily comprehended simplistic view of the ills of society,

and it also provided a scapegoat – something that was of course only possible

because feudal lords and princes had indeed used some Jews as “strawmen”

who would use princely money to make loans at usurous rates, taking interests

on behalf of Christian rulers and taking a cut. These preconceptions of

the exploitative, speculating Jew linger still, in the minds of many simple

Ukrainians, butressed by the few among the Jewish community who (like

so many others) engage in property speculation, commodity speculation,

currency speculation, and so on. And as always, seducible – indeed,

gullible – simple minds are easily exploited politically, for concrete

reasons and with concrete purposes in mind. The Nazis were neither the

first nor the last to do this.

When Jura Soyfer was still very young, perhaps 7, perhaps

older, his family fled to Austria because his father was quite naturally

opposed to the new Bolshevik government that ruled Ukraine after having

defeated others vying for power in that part of Europe. In Vienna,

Soyfer was soon active in the Association of Socialist High School

Students when he was only 17.(6) The anti-Jewish

sentiments of average Ukrainians, and memories of pogroms that remained

alive in his family, were probably a factor that explains why a man like

Soyfer turned towards the Left inspite of his bourgeois class background.

This, too, was not untypical of Jewish intellectuals in Ukraine, Poland,

or Russia. Socialism promised the emancipation and equality of all members

of the human race.

In the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, the tendency

to embrace socialist ideals – observed between 1890 and 1947 among Jewish

intellectuals (and also among Jewish factory workers) – made

Jews in many parts of Europe, including Ukraine, again a scapegoat. Now,

in the minds of right-wing nationalist demagogues, it was seemingly clear

that it was only due to them that the October Revolution had occurred

and proved victorious, and then, again due to them, everything went wrong

later on – especially the crimes committed under Stalinism were blamed

on them. Thus everything that is seen as "bad" (or "evil") was and still

is easily attributed to Jews by the nationalist simple minds. The examples

of Trotsky and Rosa Luxemburg seemed to prove the point, but also the examples

of a writer like Jura Soyfer, a pioneer of modern theater like Meyerhold,

and so on. The fact that Stalin, a native of a Christian country, Georgia,

was educated in an Orthodox monastery, does not matter. Nor does it matter

that many willing helpers working in Stalin's GPU (or NKWD) had a Russian

orthodox, or Ukrainian Catholic background, whereas Jews were (proportionally)

just as present as other groups among Stalin's victims.

Today, the Jewish population in Ukraine is only a fraction

of what it used to be before the Nazi German attack. Jews were rounded

up in those years of Nazi occupation, often with the help of Catholic Ukrainians

– or they joined the partisans, hoping to at least resist, and perhaps

survive. Today, in Ukraine, it is a fact that a person risks being slighted

and despised by the nationalists if he (or she) reveals that the father,

mother, or uncle joined the struggle of the partisans. Those who did join,

have died already. Their offspring are forced to keep silent about it among

nationalist Ukrainians. As right-wingers ascend to power in the new government,

and also in view of the general climate in many parts of the country, a

number of Jewish businessmen are often eager today to profess support for

the new regime, or so it seems at least. In all likelihood, most of them

simply want to avoid the impression of being disloyal Ukrainians. The fear

of pogroms may distantly echo in their minds. And why should they

side with Putin and with Russian nationalists? Anti-jewish sentiments

and right-wing nationalism abound in Russia, too. The stedl is a

reality of the past; the cosmopolitanism of cities like Odessa has faded

away, and those who do not fit into the neat categories preferred by Ukrainian

nationalists and native-speakers of Russian are a marginalized, obscured

minority that ducks and seeks cover, in an atmosphere of heated nationalisms.

When in 2004, Yanukovuch's victory in the run-off election

on November 21 was contested, one could see already that Western politicians

and media took sides. It seems clear that indeed there were some irregularities.

But really more profound ones than in other countries (the U.S. included)?

If there was voter intimidation, if people cast votes in the names

of those too old or sick to vote, those in homes for the ages or patients

in hospitals, this is likely to have occurred in Western Ukraine (where

it hurt Yanukovich) and in Eastern Ukraine (where it hurt Yushchenko).

As in the race that put Gore against Bush, the outcome was predictably

close – which rules out major cheating. With the country so polarized,

it was a question of taking away a few percentage points from the adversary,

by honest or dishonest tactics. On November 26, 2004, USA Today

wrote that Yushchenko's claim to have lost the election due to election

rigging immediately “won significant international backing” by the

West.(7) According to

this paper, “Western observers

[…] cited voter intimidation” – and this even though there was no

secret police to interfere; it could only be peer pressure in precincts

heavily in favor of one candidate. They also claimed there was “multiple

voting” (which is very difficult to become aware of, empirically, as an

observer), as well as a good amount of other (unsubstantiated and unspecific)

“irregularities.”(8) It sounds very much like

the typical charges brought to bear in contested elections in the U.S.,

but “[t]he United States and the European Union said they could not accept

the results as legitimate” even before the courts had investigated the

claims of the Yushchenko camp.(9) It was clear

that the American and European political "elites" were disappointed because

the man they bet on (and financed, in part?), had lost this election. Therefore,

they “warned the Ukrainian government of 'consequences' in relations with

the West.”(10) Pressing for a repeat

election, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, former National Security

Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski and Senator John McCain all visited Kiev, in

official or private capacities, in order to support Yushchenko.

On the other hand, the fact that the Supreme Court of

Ukraine in Kiev halted publication and official recognition of the election

results until charges brought by the losing Yushchenko camp had been

considered and until an investigation had been concluded, seems to speak

for a normal process not unlike that preferred in the U.S. where the Supreme

Court had the final say on the contested ballots in Florida. Russia's

president, Mr. Putin, seemed more calm and reasonable than many Western

politicians; he said, according to USA Today, that “all claims relating

to Ukraine's election should be settled by the courts.”(11)

The contested 2004 elections thus revealed already both

the conflicting interests of the West and of Putin, a readiness to meddle

in Ukraine's internal affairs, and the rash way in which the West arrived

at a conclusion regarding the “rigged election.” It seems that in

the West, only Dutch Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende took a view that

was comparable to Putin's, in stating that “setting up a legitimate government

is essential. Any objections to the electoral process must be looked into.”(12)

USA Today noted, however, that the broad and sweeping

charges brought by the Yushchenko camp made it difficult to substantiate

them. According to Ukrainian election law, the Yushenko camp should have

legally challenged “election results from individual voting districts”

– district by district, substantiating its claims concretely in each case,

rather than making a general statement that the election which gave Yushchenko

46.61 % of the vote (against Yanukovich's 49.46%) was unfair.(13)

It speaks in favor of the judicial process (and for the

rule of law) that the court nonetheless voided the election and ordered

that a new election should take place. And thus, in Kiev, for several days

in December, 2004, “tens of thousands of Yushchenko supporters rallied

on the main square of the capital in a […] show of force” – voicing their

expectation that the “repeat presidential election” should be “free

and fair.” (14)

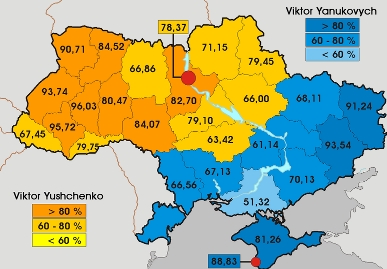

The presidential election in Dec. 2004

The expectation that the West connected with a possible

victory of Yuchchenko was clearly formulated in December 2004 by the Parisian

newspaper Le Canard enchaîné: “Si l'opposition [i.e.

Yushchenko] triomphe, il faudra alors causer de l'adhesion

de Kiev à Europe. C'est la prochaine étape, inéluctable...”

[If the opposition (i.e. Yushchenko) triumphs, it will cause

the adherence of Kiev (i.e. the Ukraine) to Europe (i.e., to

the West, thus either the E.U. or NATO, or both). This is unescapably

the next stage (of the political development aimed at by the

West and by politicians like Yushchenko, who are backed by a considerable

part of the Ukrainian population). ] (15)

It is a sign of the political independence of Ukraine's

legal system that the Supreme Court indeed ordered a repeat election. It

took place on December 26, 2004 and resulted in Yushchenko's victory. Western

media claim that Yanukovich lost because his adherents could not cheat

again. This is possible. It is also possible that the strong bias of the

media against Yanukovich and the heavy presence of Western politicians,

but also the large amount of money spent during the campaign, changed

the mood of some voters who had supported Yanukovich in November. Did this

meddling prefigure key developments in Ukraine during 2013 and 2014?

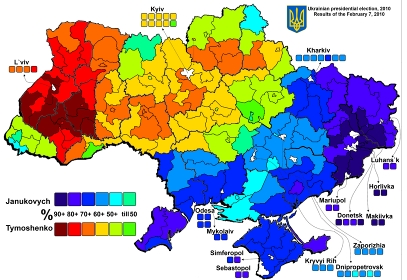

In the presidential election that took place in 2010,

Yanukovich came in first, perhaps because Ms. Timoshenko was discredited

due to what seemed to be heavy involvement in corruption. Ordinary Ukrainians

are indeed sick of corruption. In the next few years, the media had a new

message for them. Yanukovich was corrupt, too, and surrounded himself with

people who were corrupt. It was probably true.

The presidential election in 2010

During the years when Yanukovich was in power, the question

of adhesion to the European Union became prominent. Again, the West took

an active interest in internal politics of Ukraine, and this can also be

described as "interference" or meddling. Again, the nationalist West Ukrainians

were ready to produce a show of force in the streets, above all, in Maidan

Square (Independence Square), a symbolic spot in the capital, Kiev. Again,

the political camp that is less enthusiastic to join the E.U. and NATO,

the camp that embraces neutrality as a constitutionally enshrined principle

of the country, and that leans heavily on native speakers of Russian in

Eastern counties and progressives in the West and center, proved defensive:

When provocative violence (that should have been investigated independently

by now) caused many victims on Maidan Square, members of parliament leaning

toward Yanukovich were attacked, others were pressured, some votes may

have been bought, but nonetheless the quorum of 75 percent necessary to

unseat Yanukovich as elected president of the country was not attained.

In a heated atmosphere of violence, exasperation, international condemnation

by Western governments (but not, for instance, by India), the legitimate

president fled, and we could immediately witness an unconstitutional formation

of a new government under a new interim president. It may remind some readers

of another instance of regime change, when the democratically elected president

of Brazil, Joao Goulart, fled first to Porto Alegre and then to Montevideo.

It is interesting that a German – slightly left-leaning

– liberal social scientists, Claus Leggewie, declared in January, 2005,

that there exists today, in his opinion, “no path that leads back to the

Cold War.”(16) It was an ominous attempt

to be prognostic, for it revealed exactly the opposite of the manifest

content of his statement. Everyone with a minimum of clear perception of

the developments in Europe and the world, and with some analytic capacity,

had to be gripped by a premonition or fear that another Cold War was already

knocking on the door. Of course, it is no longer a Cold War between self-proclaimed

“real socialism” (or etatist “communism”?) and modern oligopolistic capitalism,

but plainly between major capitalist powers. Leggewie described the

factual “prohibition to intervene in the inner affairs of states

governed in authoritarian fashion” as a constitutive element of the past

Cold War situation. Quite obviously he does not imply that

the U.S. would not intervene in Greece, in South Korea, in Iran, in

Indonesia, in Lebanon, in the Dominican Republic, in the Congo when Lumumba

was toppled and murdered, in Brazil when Joao Goulart was ousted, in Greece

again, and of course Turkey and Cyprus, in Italy (during the straghe

period), in Vietnam and Cambodia, in Guatemala (twice), in Chile, Argentina,

Bolivia, Uruguay, in El Salvador and Nicaragua, in Cuba, in Angola, in

Mozambique, in Haiti, in Columbia, in Venezuela, in Iraq, Yemen,

Somalia, Libya, Syria, Egypt. And perhaps I leave out a few examples. In

fact, they did intervene, in direct or indirect fashion, sending

the marines, sending experts, advisers, special forces, sending an entire

army, supported by the navy and the air force – there were always

so many ways and shades and intensities of meddling violently in another

nation's (and people's) public affairs. To enumerate merely such places

of intervention can gives us an idea of the scope of American neo-imperialism.

But it does not mean that the Soviet Union – or China, for that matter

– did not meddle in the affairs of other countries after 1945 or '49; the

Chinese most notably in the conflict between Vietnam and Cambodia, and

by supporting movements in Angola and Mozambique that were financed by

the U.S. and the apartheid regime, as almost everybody knew. And yet, Leggewie

is right in one respect: there existed mutually acknowledged spheres of

interest. The U.S. would not have dared to intervene militarily in Egyp

under Nasser for instance, and Soviet threats reigned in Anglo-French aggression

during the Suez crisis. Egypt was acknowledged as an ally of the Soviet

Union that the government of that country would try to protect. The big

superpowers were not keen to engage in direct military confrontation. Certainly

not over Egypt. The U.S. signaled Britain and France (two subimperialist

powers still invigorated, at times, by colonialist arrogance) that they

better stop it. Washington would not accept being pulled by them

into a military confrontation with the Warsaw Pact.

These things are a matter that belongs to the past. The

sole superpower that is left after the collapse of the Warsaw Pact, and

after an already weakened and discouraged Soviet Union was dismantled,

is today a power filled with the belief that nothing can stop or limit

it. It is ready, it seems, to take new risks – bigger ones than it was

willing to take in the Cold War. Leggewie interprets this lack of risk-aversion

in terms of America's democratic mission and missionary spirit, and he

suggests that Europe (i.e., the E.U.) should be ready to compete

with the U.S. in a joint effort to “spread democracy, freedom, and participation”

in the world. This is exactly what got us into the “humanitarian war” on

Yugoslavia and what destabilized Afghanistan and Iraq and Libya and Syria,

perhaps for a very long time, at tremendous human cost – and all in the

name of spreading democracy. It is what is adding fuel to the fire of war

that burns in Eastern Ukraine, and it conjures up the spectre of a much

wider and more horrible war. Leggewie, however, regretted that “humanitarian

interventions are still regarded with suspicion.”(17)

It is time to ask what it would mean if the West intervened militarily

in open fashion in present day Ukraine, claiming that the increasing

number of victims of a civil war that would never have erupted in the first

place without Western meddling, prompts it to embark on another “humanitarian

intervention.” It is also time to ask what other measures that the West

has taken or is prepared to take might bring us closer to war. We have

seen an escalation on the verbal level. We have seen efforts to wage an

"economic war." We see NATO bases edging closer to Russia. And we see NATO

planes and soldiers very close, indeed, to Russia's borders. Perhaps we

should not take the warnings of high-ranking officials in Russia lightly

that they will take only that much, and will act if their country's security

is imperiled in ways that go too far.

- Martha Wols

NOTES

(1) N.N., “In Ukraine, language is an election

issue,” in: International Herald Tribune, Dec. 23, 2004, p.3.

(2) N.N., “In Ukraine, language is an issue,”

ibid.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Ibid.

(5) Regarding Jura Soyfer, see: Erich Hackl, "Die

Farbe der Welt [The Color of the World], in: Junge Welt (Berlin),

Dec. 8-9, 2012, pp.10f.

(6) It was then that Soyfer published ´his

first poem in Schulkampf, a journal of this association. When

Soyfer was in his early twenties, he was already publishing satirical poems

in the German-language newspaper Arbeiter-Zeitung, the party newspaper

of the Social Democratic Workers Party of Austria (SDAP), a party

that proved its independence by developing so-called Austro-Marxist

theoretical positions. Perhaps it was not only the fact that he was now

living in Vienna which compelled Soyfer to write in German, rather than

in Ukrainian or Russian of Jiddish, but also that other fact that Jiddish

is so close to the contemporary German language. His choice thus resembles

Kafka's – for Kafka could also have opted to write in another language,

in Czech or in Jiddish, but he chose German. As Erich Hackl reports, Soyfer's

Hungarian friend Marika Szésci admired his integrity, his humor,

and his talent as a poet. Hackl mentions Soyfer's friendship with Erich

Fischer and notes that Soyfer was later imprisoned in Austria by the fascists.

Released in February 1938, he was again arrested while attempting to cross

the Austro-Swiss border. He was sent to Dachau, then to Buchenwald where

he contracted typhoid fever. On February 1939, in the darkness of night,

Soyfer died in Buchenwald, already a concentration camp, as the death camps

were called in those years.) See: Erich Hackl, ibid.

(7) Anna Melnichuk, “Ukrainian court halts publication

of elections results,” in: USA Today, Nov. 26, 2004, p.4.

(8) Anna Melnichuk, ibid.

(9) Anna Melnichuk, ibid.

(10) Anna Melnichuk, ibid.

(11) Anna Melnichuk, ibid.

(12) Anna Melnichuk, ibid.

(13) Anna Melnichuk, ibid.

(14) N.N., “In Ukraine, language is an election

issue,” International Herald Tribune, Dec. 23, 2004, p. 3.

(15) N.N., “Ukraine et chouchous de Bruxelles,”

in: Le Canard enchaîné, Dec. 8, 2004, p.1.

(16) Thilo Knott, interview with Claus Leggewie,

“Kein Zurück zum Kalten Krieg” [No return to the Cold War), in: taz

[die tageszeitung], January 22/23, 2005, p.3.

(17) Thilo Knott, interview with Claus Leggewie,

ibid.

|