Authentic Political Art

Paintings by Angelo Evelyn that reflect threats of war,

also of war on nature

| Perhaps nearly everybody in the art world, regardless

of whether we speak of critics, visual artists, or those among the public

who care for art, knows instinctively that you cannot command artists to

create political art. At least not, if you hope that the result will be

art, rather than something that is on par with advertisements for

Coke, seen on a large billboard. Regimes of every kind and color, from

constitutional monarchies around 1914 to fascist dictatorships, from liberal

republics in the Second World War, to Socialist governments in that war

and its aftermath, have tried to harness artists and make them respond

to"the call of the country" or of a class. It never works.

But that does not mean that visual art cannot convey sentiments

and reveal hopes, that it cannot speak of fears or instill a craving, perhaps

even for a more humane society. a world without war. The point is that

apparently you cannot order artists around, you cannot order them to feel

this or think that. Either it happens inside because this is alive in them,

or you get a fake, a sterile response to some request, whether of a paying

customer, or a dictating power.

But then, you will say, artists have for centuries been

servants -- of a church that demanded attachment to religious topics, or

of kings and aristocratic local rulers who wanted to be honored, respected,

eternalized in art, and who thought they could get it by promising rewards.

When merchant capitalism took roots in the 16th century in the Low Lands,

painters like Rubens of course painted for paying customers. Did

it make later leaders, from Cuba to China, think that it works -- that

artists can be disciplined, that they can sell their soul?

It is a mean question because it presupposes what

ought to be proved: that the leadership of Cuba for instance, WANTED to

armtwist painters or writers. That they did, in a number of cases, cannot

be disputed, I think. Still, it is possible that they hoped artists and

writers would freely, voluntarily, authentically embrace a revolutionary

ethos.

Some did. Others found it too difficult when they saw

that they were not allowed to both support and critique the revolution.

Still others never wanted to support it, perhaps.

In Cuba, the leaders said, "Within the revolution, everything

is possible; against it, nothing." If practiced, if not an unkept promise.

writers like Heberto Padilla would not have run into problems. It was those

up there, "at the steering wheel," who decided what was "within the revolution."

Heberto could think he was "within" it and that it would help the process

to build a better Cuba, if one could critique, and also express sadness.

He learned the hard way that it would not be accepted.

This makes many progressive artists and painters seek

a certain independence from governments. They think, "It is possible to

show solidarity -- but we will never give up our independent mind, our

critical faculties, our authentic emotions, just in order to conform with

a decreed sense of partisanship, of solidarity with the poor and exploited,

the wretched of the earth."

This said, it should be clear that there are two kinds

of political art. Commanded art, or art that gives in to expectations formulated

by others -- whether the "masses" or governments.

And art that reveals a political stance because the artist

-- the painter, print-maker, sculptor, filmmaker, or author -- is a politicized,

a politically aware citizen.

It is of the second kind that quite a few of the paintings

by the Canadian artist Angelo Evelyn seem to be. They reveal the

artist as a kind of seismograph, aware of coming social or political shock

waves. But they reveal him also as a clear-minded, informed, politically

aware, and committed individual.

In the 1980s, this expatriate artist who was living at

the time in Germany, reacted in a number of paintings to the increasing

Cold War tension associated with the decision of the U.S. (and of NATO)

to station medium range missiles with nuclear warheads in Italy and Germany.

There were protests in front of the U.S. base at Comiso (Italy) and Mutlangen

(Germany) at the time. In Germany, the Nobel Prize recipient Heinreich

Boell and Walter Jens were among those taking part in peaceful sit-ins

in front of the Mutlangen base. The presence of such "celebrities" (celebrities,

in the eyes of politicians, the mainstream media, and consequently, the

police) helped soften the approach of the forces of disorder: Instead of

clubbing demonstrators brutally, as was normal, they would politely carry

them away and charge them with trepassing. Courts would fine the participants

in the sit-in rather than send them to jail. Perhaps as the result of the

relative success of the sit-ins (a success which was above all mediatic,

causing attention of the mass public, with the consequence that one hundred

thousand demonstrators came to the big demonstration in the West German

capital, at the Bonn "hofgarden"), the laws were rewritten thereafter,

redefining peaceful sit-ins not as a misdemeanor, but as an "act of passive

violence." Thoreau and Gandhi would have been aghast. What an Orwellian

invention of Newspeak: it shows how not only language but democracy was

subverted. It did not start with George W. Bush's warrantless wiretapping

of millions, you see.

In the 1980s, Angelo Evelyn, as resident artist in West

Germany, was fully aware of the increased danger of nuclear war. A pre-emptive

strike of the Soviet Union that was cornered by freshly stationed missiles

that would reduce their "warning time" to a few minutes, was at least thinkable.

The strategy chosen by NATO was full of recklessly taken risks.

Here are two paintings that reflect the psychological

turmoil caused in many contemporaries in Europe at the time.

|

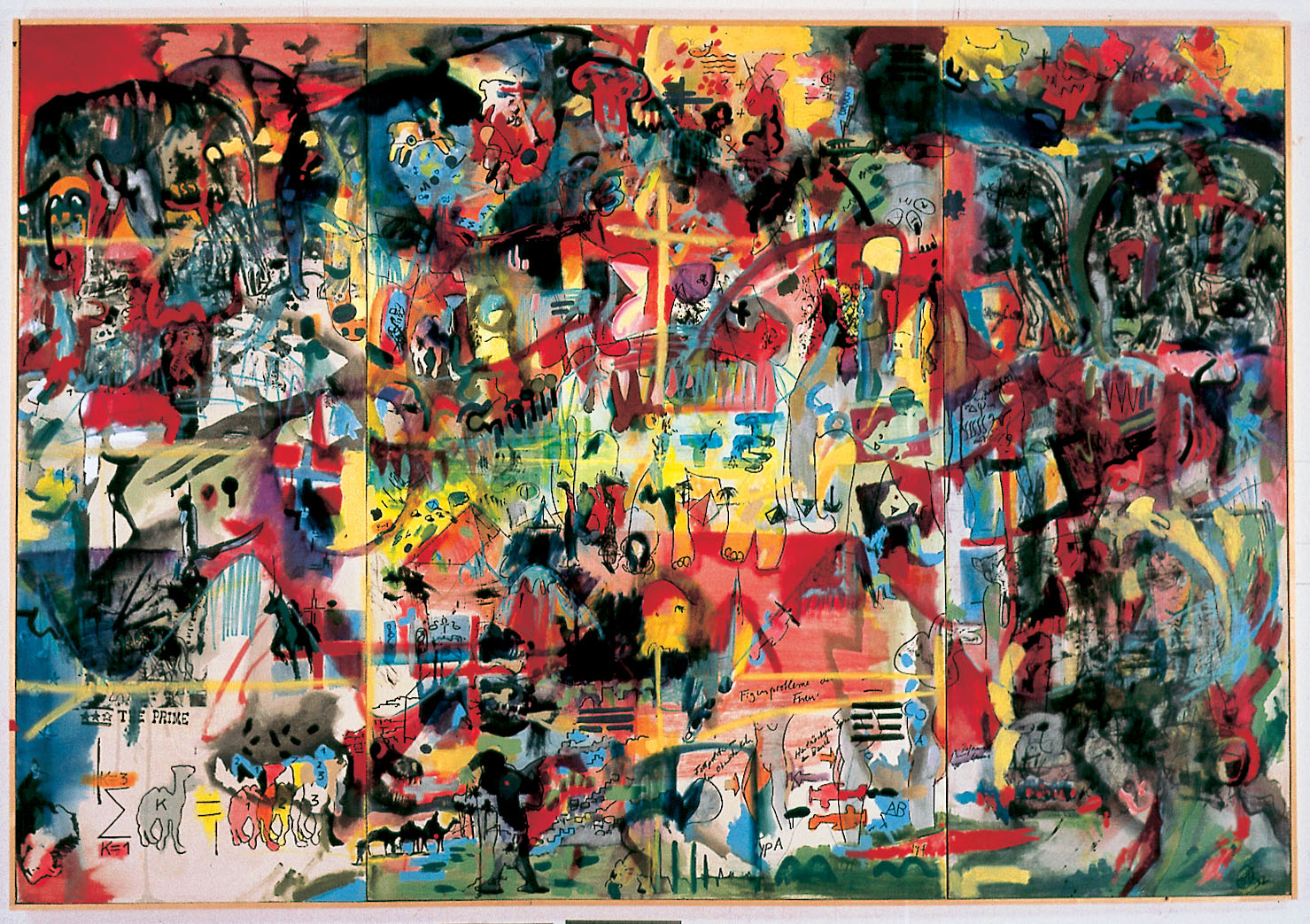

| The first painting shown here reveals a turbulent rhythm

and a cacophony of colors. Enigmatic silhouettes of animals - camels, elephants

and others - populate a landscape that shows few landscape qualities. This

is no Serengeti, no prairie, no Congolese jungle - it is the asphalt jungle

of Montréal or Berlin, places where this painter lived and painted

for some time. And the animals seem like embodiments of fears and dangers,

of movement, of apprehension, and also of aggression and defense. |

The work shown in this photo, taken in the Rotterdam

studio of the painter, with his wife in the foreground, reveals a nightmarish

vision of World War II aerial attacks. It could be war in Vietnam as well,

with B-52s dropping napalm above rice fields. Is anti-aircraft flak countering

the attack? Are people, like shadows, or silhouettes, appearng out of dust

clouds, clouds of explosions? Bleeding to death on the ground, or hovering

in mid-air? There is no central perspective, and yet we sense a place,

a space, we sense what is UP THERE and what's at the BOTTOM of the world.

Colors flow and fuse, but in a darker, more threatening way than in Nolde's

paintings. Apart from the silhouette of planes in clouds of color that

suggest a sky, and guessable human shapes, no form resembles things in

the way we expect to discover a semblance in figurative painting.

|

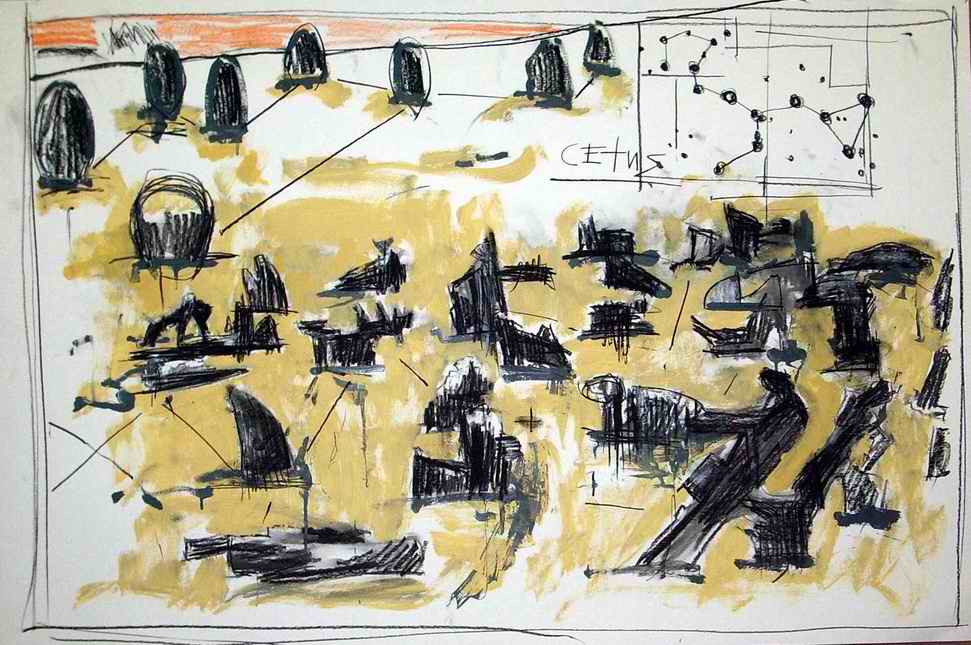

When Angelo Evelyn, more than a decade later, visited

a land art ensemble in Southern Germany that its creator, the artist Wuensche-Mitterecker

intended to record his memory and vision of World War II battlegrounds

(sites encountered as a painter, dispatched by the German army), a number

of works like this one originated. The hilly landscape, the valley with

its sculptures -- a green space in summer, a white one in snowy Bavaria

winters -- becomes an empty plain. The emptiness between the objects is

emphasized, and thus a feeling of desolation results. The human shapes

of the sculptures -- in one case it is also the sculptured figure of a

fallen horse -- have become strange and difficult to decipher. The force

of the pen is felt; drawing these objects has almost become a violent act.

In comparison, the almost monochrome, light ochre color seems to have been

applied lightly. in a painterly, soft and almost tender fashion.

The landscape is wide and the figures are as if lost,

in this wide expanse. Is it the way we humans are lost in death, lost in

our lonely way of dying? One of the objects placed in this cold, lonely,

desolate world appears to me as a stoic creature, perhaps a sheep. The

other animal lifts its head quietly, as if pensive, and faintly curious.

A star constellation is juxtaposed, perhaps suggesting the incomprehensible

workings of fate.

In more recent times, the tackling of a subject like war

has taken different forms. It is as if war on nature has preoccupied Angelo

Evelyn.

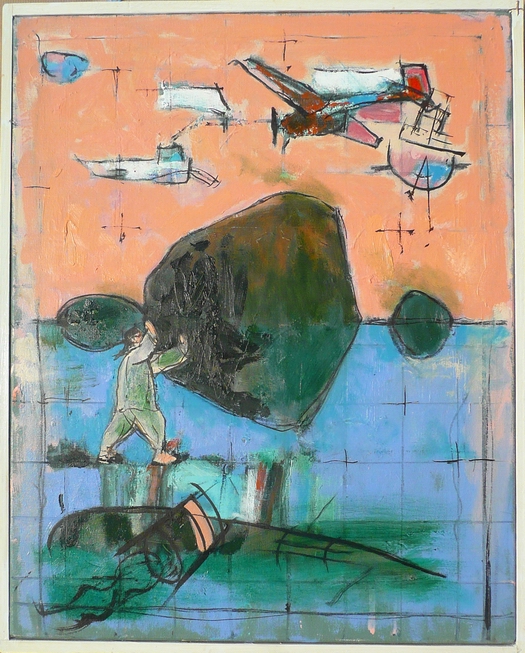

Here, a human figure makes a gesture as if to ward of

imminent dangers, symbolized or at least represented, by a plane, another

object n the sky that could be a satellite, and a flying boat. Forms that

reoccur in his paintings of a Canadian island stud the horizon, their shape

mirrored in what must be the water. Memories of his native region, Vancouver

and Vancouver Island, come to mind. In the foreground, a boat seems to

have capsized. And a barrel, turned over, is spilling some poison-green

fluid into the sea. The recognizable trace of a pen, combined with the

colors applied, has resulted in a strange, well-balanced work, executed

not unlike some works by Jim Dine, but with a strange, almost surrealist

touch to it.

The next painting included here captures, in painterly

fashion, a landscape in Ontario, a Northern sky, filled by strange, almost

ominous light, and islands in what must be a lake or a combination of lakes

joined by a connecting river. It is a large work, consisting of three

panels that presents this landscape panorama. The world shown is at odds

with itself -- both extremely peaceful, lonely, empty, devoid of human

habitations -- and yet disturbed. There are leafless, barren tree trunks

in the foreground. A plane has settled down on the lake, swimming on its

surface, or is it about to land, but still several feet above the water?

Two small boats are visble on the water, but they are empty, there are

no humans. Apart from the barren trees, it is the presence of the plane,

and its strange green color, that suggests something disturbing, destructive:

the intervention of man. |

Very recently, the war on nature lights up again in a

number of "Dutch paintings" -- featuring the lowlands of that

country, with its many big and small canals.

Strange forms, like transformed, aggressive suns, appear

in the sky. Men who could be qi-gong practioners, make gestures

that seem symbolically defensive -- do they attempt to ward off global

warming, or some other threat? The serene landscape, consisting of

flatlands crossed by canals and a line of trees along the horizon, is like

an occupied country. What may be glass houses, positioned on those meadows,

discard strange fluids into the canals. Star constellations are juxtaposed

next to the qi-gong practioners and superimposed on the land.

Do I see a helpless dog or sheep in the foreground, and the body of a large

fish swept onto the yellowgreen grass? This world is in trouble -- so much

is clear. But the painting, excecuted across four panels, shies away from

extremes: the colors, apart from the bright red sunlike celestial bodies,

suggest an almost idyllic state. The two sun-shaped red bodies, in the

foreground, that seem to sink into the water, are aggressively red, however.

And one of the four men we see, has flashed a rising stream of white mist

or light upward, towards the stratosphere. It is as if he has made use

of a secret, yet magic weapon. But why, and with what effect? |

| In this painting, the sun has turned almost black, its

rays are spikes or thorns piercing the sky. Again we see flatlands, traversed

by canals in that typical, very Dutch way. The panels are distinctly separate

as illusionist parts of a painting that evokes a typical landscape.

Smoke from a fire seems to rise into the sky, on the right-hand panel.

Here, too, in the central panel, we see water polluted by industrial agriculture.

The world is in disorder, and people begin to sense a threat. |

- Carla Voss

go back to Street

Voice # 14, Contents

|