| Gene

Markopoulos

Some Observations on “Spring Cactus” (Zheng qing kuang

ai) – A Film by Yu-Shan Huang

What makes a feminist filmmaker like Huang Yu-shan turn

to the factual story of a young girl or rather, a very young woman whose

story makes the headlines because she was involved in juvenile delinquency,

later on became a prostitute, and finally committed suicide at age 28?

Is it a empathy? Is it anger, directed at a society still embracing too

many patriarchal values, a society largely dominated by men? Of course

you encounter them on every level, as teachers, preachers of morality,

journalists, judges, cops, customers of brothels and pimps. Spring

Cactus (Zheng qing kuang ai) is the “true story” – we are told

– of Chen Ai-Lan. And we are also informed that the film was “made possible”

only “after a few years of field investigation.”

As so often in such cases, the protagonist of the film

is raised in a family where problems abound. Soon, she is also taken

for a problem child. While still in high school, a sentimental love develops

between her and Xiao Lin, who is seen by adults as quite the opposite of

this ‘saucy’ girl, an exemplary student, so to speak.

As would be typical for any romantic melodrama, their

friendship faces the resistance of a world of righteous adults. It is Xiao

Lin’s parents who are the most concerned; they turn to a teacher, expressing

their fear that the girl is a ‘rotten apple’ who might have a bad effect

on their son. When the two young people find it impossible to factually

continue their friendship, the boy kills himself and the girl runs away

from home. Out on her own in the city, she encounters Chen Mingdao, a young

man who is doing social work, as a candidate of a Buddhist order which

he aspires to join, as a monk. But bye-bye, chastity and existence as a

monk. The two get married. A marriage of very different persons, it seems

– so conflicts must erupt, perhaps. One day, in a fit of anger or impatience,

the girl attacks and wounds Ming-dao badly. She is imprisoned. On her own

in the city again, after having served time. Yes, she meets a guy who is

willing to “protect” her. She walks the streets, she smokes, drinks, takes

drugs. And yet she is tender. Cannot even refuse a beggar’s plea for money.

But the guy who “protects” her is no good. Is there ever a pimp who is

good, who does not beat up his girl? We can almost predict that the day

is not far when she attacks and kills him. Again, she lands in jail. Out

of jail again, this time it is Blacky whom she encounters soon after she’s

left jail. Blacky belongs to the dark world of the city, too – he’s a gambler

and bad-tempered, at that. Her life gets darker and more confused, as she

tries to make a living, as a prostitute, supporting herself and Blacky’s

gambling habit. Then, strange coincidence, she chances upon Cheng, a Buddhist,

known as a Dharma Master. Is it superstition? Is it the chance moment the

surrealists celebrated? Something in this encounter seems to have made

a difference, or so we are briefly lead to believe. For all of a sudden

the protagonist knows she wants something else. She’ll stop taking

drugs, she tells herself. She will be a different person, living a different

life. Starting truly from scratch, she wants to shake off the past. But

soon we learn that the peace of mind she found briefly, and the inner purity

that survived in her have no chance to persist in society as it is. The

world of the righteous ones, the hypocrites, the respectable people does

not forget whom it has cast aside. No Buddhist salvation, no mercy is possible.

And the righteous ones will always have their counterparts and willing

helpers in the dark world. When the female anti-heroine, our tender, rebellious

protagonist, attempts to begin a new life with Xiao Mao, a guy she encountered

and befriended while in jail, she is betrayed. Having lost all hope that

a turn-about, a new life, is possible, she takes her life, in a final gesture

of protest and rebellion.

Huang Chung-ming, in his short story Sayonara Zaijian

dwelled on the topic of prostitution in Taiwan many years ago. That it

is a social issue to deal with, and one that must get feminists on the

barricades, is clear to anybody who has seen the teenage girls working

in the many “barber shops” of small towns like Tamshui, of harbor towns

like Keelung and Kaohsiung, and of the various villages by the sea that

are inhabited by fishermen and their families. Of course, there are also

the luxurious whores loitering in the lobbies of five star hotels in Taipei.

Or in Yangminshan – that spa in the mountains above Taipei, so well-known

for its hot sulphor springs. But that is another story, as is the story

of the college girls who work as escorts in ‘dance halls.’

Huang Yu-shan’s film is remarkable for a number of reasons.

One of them is the filmic language she has found in order to narrate this

seemingly simple, melodramatic story that seems so full of romantic stereotypes,

at least from the point of view of the male chauvinist skeptic.

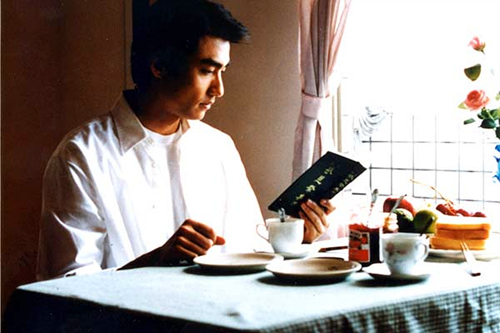

Xiao Lin

The shots are well-composed, to begin with. Look at the

still that shows Xiao Lin at the breakfast table, ignoring both fruit and

toast, the dish clean because he hasn’t eaten anything, the jar filled

with jam untouched. It is a Western breakfast, not a traditional Chinese

one. Probably he drinks coffee instead of tea. The expression of his face

is earnest yet not stiff. At ease with himself, he fully concentrates on

the book he is reading. No voice over, no narrator is necessary to tell

us what kind of person he is. A good son, a sensitive person, dedicated

to a world of books, a world of ideas. A vulnerable person, not the typical

slick yet rough male who succeeds in the “world outside”. So little, carefully

selected, is needed to tell so much in a single shot. But do you notice

the spatial dynamism of this image? The diagonal position of the table,

and the way, therefore, in which Xiao Lin is facing us? In fact, his chest,

in that white shirt, is catching our attention. The face looks away from

us, a little slanted, directed with great intensity, at the page of the

book. Are the colors telling us anything? There is so much whiteness, so

much light, contrasted by the darkness of an edge or section of the table

cloth, the black of the book cover, the warm pastose red-brown of the wall

in the back of the young man. In the West, we know, light was sometimes

taken as a symbol of enlightenment. And here? Maybe, too.

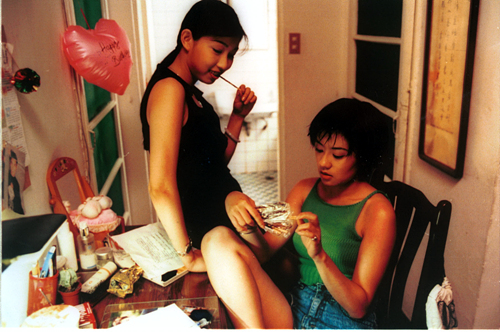

Ai-Lan and another girl

Here, we see the crammed room of the female protagonist

who ekes out a living as a whore in order to survive in the city.

There are the paraphernalia of a teenager’s life. In a brothel? Yes,

in a brothel, too. A red heart saying “Happy birthday”. A mirror. Other

small items which will make men wonder what they mean or what use they

may have. The girls are talking. About boys? About hopes harbored? How

pensive the heroine is, as she looks at that item she holds in her hands.

And how intensely the atmosphere of a small, crammed room in a whorehouse

has been recreated. But don’t kid yourself – a room in a students’ dorm

would not look different perhaps. And these girls are not different from

the girls who are not forced by circumstance to sell themselves.

The mirror again! Azed Yu, in her fine text on the films

of Huang Yu-shan, has already pointed out how significant they are. The

symbol of self-awareness of young women like Ai-Lan?

The madam and Ai-Lan

Again, the composition of the image is superb. How much

sensitivity is needed to attain this interplay of a space filled by two

persons, a space visible in front of and then, in a mirror!

There is the older woman, a stalwart of the oppressive, sexually exploitative

“male world”. How stern she looks, in her elegant, almost traditional

Chinese dress that could have been worn already in the more expensive whorehouses

of Shanghai in the 1930s, by such a stern looking madam. The dress fully

covers her, except for the hands, the throat, the face. And the darkness

of its pattern underscores this impression. Facing her, there is the young

girl. With her nude arms, her nude legs raised high as she draws the knees

close to her body, she seems to be almost naked. Does she look as if at

a loss? Frightened? Or asking for something? Help that she cannot get?

A life line? In the mirror, she looks more adult, cooler, but also very

much on her own. The madam is not mirrored.

In the mirror that projects the small, distant image of

the girl, we discover darkness, but also white curtains and the light entering

through that window which must exist behind these curtains. Reduplicated,

the curtains that cover the window exist as well right behind Ai-Lan. Do

they separate her from something, do they make her appear like a bird in

a cage, inside this room? Do they keep out a different, and perhaps also

freer world?

Thanks to the window behind those flimsy curtains, the

right side of the image (the side of the girl !) is flooded by light. The

darkness is seated opposite her. Is that symbolic?

The piece of furniture in front of and underneath the

mirror is positioned diagonally, which enhances the spatial dynamics of

the image. The colors are by and large warm and aglow, contributing to

the impression of an almost luxurious boudoir or a dressing room. As she

stares at the madam, the girl, Ai-Lan, clasps what seems to be a medallion

on a chain, stretching the chain. It is as if she is a little pig or a

lamb with a rope around the throat. Torn towards the master and butcher.

Ai-Lan

I rarely saw such loneliness, such lostness in a single

instant. Out in the cold night of the city, in some place where animals

seem to be kept in cages, she squats and smokes a cigarette in front of

the grid pattern of the cage.

It could well be that she is imprisoned and that the others

are outside the cage, I thought for a moment. But of course, she is outside,

on her own. Living her existential freedom, her lonely revolt en route

to defeat and doom. A lost, deserted yet lovely and lovable person. Her

face full of loneliness. No illusions any more. No hope or not much

of it that is left.

Ai-Lan and the small cactus flower

“She was like a cactus left in the desert to flower,”

Bae Doo-Rye said. Yes, indeed. Azed Yu pointed out how the filmmaker, Huang

Yu-shan, introduces such symbols as the cactus, visible in this shot, again

and again in her entire oeuvre. I would underline the non-symbolic presence

of the face, of its expression that is both sad and tender, close to or

already beyond the point of utmost despair. How tenderly she holds and

looks at this small living plant. A tender, lovable plant – if we accept

that it needs spikes that sting.

Yes, it is true – in creating this film, Spring

Cactus, Huang Yu-shan has created a sentimental melodrama, full

of clichés, if we just concentrate on the story line, the script,

in fact. But each sequence and each shot gives us a cosmos, a small human

universe full of closely observed details and alive with genuine emotions.

Is the film uncritically reproducing conventional notions?

I don’t think so. It picks up such notions in order to deconstruct them.

The saucy, bad girl is rebellious for a reason, and if not almost pure

at heart, then at least sensitive, vulnerable, filled with a sense of justice,

which explains why she explodes, in certain situations, not being able

to take any more what men do to her. The Dharma Master, and thus Buddhism,

does not bring enlightenment and salvation – even though the empirical

reality that sensitive Buddhists exist is not denied. But they are as helpless,

vis-à-vis the society they encounter, as this sexually exploited

young woman.

As Bae Doo-Rye noted already, idealistic exhortations

are impotent in our modern, male-dominated, market-oriented society

today where everyone and everything can be bought for money. And so, “Mingdao’s

parting words, that no one can change you but yourself, seem rather unconvincing

when institutions like school or family turn a cold shoulder and society

hands her a pair of handcuffs while demanding of her to ‘come to her senses.’”

(Bae Doo-Rye)

In an unobtrusive way that avoids everything overly pithy,

the film gets this across. And this, in addition to its close and intimate

observation of people and situations, its careful composition, is a great

achievement.

If I have called Spring Cactus a melodrama,

let’s not forget that Fassbinder also created many films that are aptly

called melodramas.

(April 2011)

Spring Cactus, directed by Huang Yu-Shan, Taiwan, China (1999),

35mm, color, 105’

Screenplay by He Hsin-Ming and Huang Yu-Shan

Cast: Chia Ching-Wen [Jia Jing-Wen], Hu Ping [Hu Bing], Lin Li-Yang,

etc.

Cinematography: Chang Chih-Yuen

Sound: Liao Chi-Hua

Editing: Huang Yu-Shan

Music: Chen Shin-Hsing

Production Designers: Yao Yo-Shun, Tang Yi-P

Producers: Chang Shih-Kun, Shu Tzu-Hao, Huang Yu-Shan ?

Produced by Hsing Lee and King Ho, Huang Chen ?

Executive producer. Shih Hun Chang

Distributed by: Taiwan Film Culture Company and

B & W Film Studio

|