| Andreas

Weiland

"The Strait Story", a feature film

directed by Huang Yu-shan

The Strait Story (Fu Shih Kuang Ying), feature

film directed by Huang

Yu-shan, 35mm, color, 105', Taiwan, China (2005).

Cast: Freddy Lin,

Yuki Shu, Chang Jun-ning, Lin Hong-shiang, He

Hao-jie, etc.

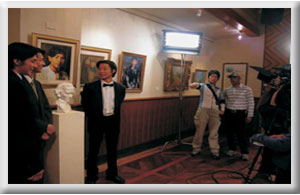

Huang Yu-Shan, the director

of The Strait Story, withYuki Shu who plays the role of the art restorer,

Xiu-xiu [also transcribed Shio-shio – a name pronounced somewhat like Show-show]

The Strait Story is a feature

film, fiction and yet, somehow, almost semi-documentary. And this

both with regard to its formal devices, that is to say, its different ways

of inventing and presenting the “facts” of a life, and in so far

as research was necessary to find out such facts. Facts about the life

of the protagonist. For the film narrates a story about a man who actually

existed: Huang Ching-cheng. A painter who was, in fact, a relative,

a family member of the director, Huang Yushan. Through the images chosen,

the shots, the sequences, through color, the sound-track, and so on, she

tells us the story of his remarkable life but she also focuses on the search

for its traces. It is apparent that by and large, the film tells the story

of the painter’s life in chronological fashion, from childhood to

the very moment when death is very close. And yet, this story gets interrupted,

again and again. And so, in formal terms, we cannot fail to note the changes

inscribed in the mood (or warmth?) of the film as a whole. Changes

of the temperature of the colors, for instance. And then, there are

the concomitant changes that appear. It is a “to and fro”, between

two separate realities. On the one hand, the surroundings, the figures,

the voices of the past: Of the protagonist, Huang Ching-cheng, that is.

And of the people he encounters in that stretch of the past which is the

time of his life. But, on the other hand, there are the settings

and people and voices of today. Clearly, the strand of the film that represents

the present focuses to a large extent on reconstructing the painter’s work

(and life). There is above all the young, handicapped, perhaps fatally

ill woman who works as a restaurateur, a conservationist of art works -

thus, paintings, sculptures and pottery. And so, in the context of

the film, we see her above all as a specialist engaged in finding and carefully

restoring surviving but often damaged paintings of this ‘nativist’, very

Taiwanese painter. She relates at the same time to illness (her’s) and

as much, to her boyfriend or fiancé. And what she gives us, the

audience, is a lesson in female emancipation, but also a sense of what

serious work and true respect for the modern artistic heritage of the island

means. It is her stubborn determination to do a fine job, to advance

the discovery of an almost lost artistic oeuvre that we learn to appreciate

and take as an example. But we recognize something else, above and beyond

this. It’s the importance – to her – of her independence. An independence

that matters more than all her longing for warmth and a relationship of

mutual trust and that she attains both through her work and her emotional

maturity. It is preserved in a tender relationship of love – a relation

in which her friend, somberly looking at a passing train in the final sequence,

is learning a lot and still has so much to learn.

The way the film switches between

the past and the present is clearly marked, I said. Different personnel,

different voices, different colors. There is the clear rhythm of changing

worlds and times, and the viewer of the film has no difficulty to recognize

each world for what it is: colonial Taiwan, pre-war and war-time Japan,

the Taiwan of today. Our ears and eyes sense the difference: Now

we hear Taiwanese, then Japanese and on another occasion Chinese. Here,

we see the fictional representation of the child, the adolescent growing

up in a village of the Pescadores (Penghu); then, the young man who is

going to Japan to study art in the late 1920s; later, the artist who attains

a certain measure of recognition, even in that country, who will return

repeatedly, before he finally says his last words (we assume) to his lover

or fiancé when the steamer that brings him back to Taiwan is torpedoed

by an American submarine in the Taiwan Strait, close to Keelung harbor.

There, we note the pseudo-documentary search for the remarkable work of

Huang Ching-cheng. and for traces of this Taiwanese artist who died too

soon. This quest to understand the painter, to find again and see

and appreciate his almost forgotten work is a search that has its own significance,

in the narration of the film’s story. We know of course that the mode of

its presentation in the film must let us identify it as fiction (that is

to say, fictional search, filmic narration of a search). And in so far,

it is on par with the rest of the movie, as fiction. But it has a

function above and beyond framing the repeated, elaborate fictional

“flashbacks” that represent images of the painter’s life; it is more

than the decisive, rhythm-producing filmic device, more than a certain

number of intricate and in a way, experimental fragments of

a “frame”, in a movie we recognize as a “framework story”. Despite its

character as fiction, it must nevertheless reduplicate somehow the

real search preceding the film; and this is what I think turns it – and

the rest of the film as well? – almost into a semi-documentary work.

A question comes to mind, in this

regard: Are the art works we see as restored works of the painter, actually

real, authentic works of Huang Ching-cheng? I think in all seriousness

that this is possibly the case. This would be another indication that indeed

the fictional and the documentary cannot be clearly separated in this film.

There are aspects of this art work, this art film created by Huang Yushan

and her co-workers, that let the theoretically abstract dividing line between

the fictitious and the document, between feature film and documentary,

appear as fluid, permeable, as something that is almost imperceptibly crossed

numerous times, and yet we sense all the time that it must have been crossed.

Class reality is touched on, allusively,

in this film. Especially in the case of the village girl who was the first

‘model’ of Huang Ching-cheng. But by and large it is present in a reduced

way. The ‘common people’ we face are largey ‘middle class’ (to use a term

employed by bourgeois liberal sociologists). They are merchants, some presumably

with a landlord (gentry) background, and ‘educated people’: their offspring.

If peasants, fishermen, hawkers, quite generally poor people appear, their

appearance is fleeting, momentary, marginal. Even the girl just mentioned,

who probably loved Huang Ching-cheng, only appears briefly, two or three

times. In Penghu, we learn (is it a narrator’s voice?) it would probably

have been impossible that the two, as offsprings of families with a very

different social rank, could have married.

The Japanese occupation is referred

to more openly but in a differentiated way that allows us to recognize

not only its discriminatory aspects that turned the inhabitants of Taiwan

into second class citizens of ‘Greater Japan’. We also discover the existence

of good relations between ordinary people of both countries.

The segmented pieces of the “frame”

that represent today (and today’s look back, at another period) alternate

beautifully with the blocs or sequences that represent the past. I think

that the mood of the colors that represent NOW is colder, but also clearer

than that of the colors in which everything that happened THEN is visible

to us.

Huang Ching-cheng [Freddy Lin],

with his lover or fiancé, in his apartment / studio in Japan

The sequences that represent the

past are largely shot in a studio, it seems. The lighting here appears

more subdued, sometimes verging on the dark. We encounter dimly lit indoor

settings and a number of evening or night scenes in the parts that refer

to the painter’s stay in Japan. This, as well as the final sequence showing

the small cabins and narrow corridors of the steamer, then the dark sea,

leaves in me an impression of a somber, melancholic past, almost

forgotten and now emerging again. Much of it has the historical aura we

also tend to attribute to sepia colored photos.

Huang, at an exhibition

The fine art restorer, Xiu-xiu

[Yuki Hsu] , at work

When the film turns to the present,

there is more light, I think. Is it the abundance of light, the factual,

anti-auratic quality of the colors that produces a sense of harsh unmitigated

‘closeness’, a clear awareness of ‘presence’?

Indeed, these parts of the film

that portray ‘today’ appear to me as more present: visible in greater clarity.

They are more ‘undisputable’, less endowed with the quality of an unfolding

memory, a glimpse of something long gone. Do close-ups contribute to this

effect?

Xiu-xiu [Yuki Hsu]

As there are two narrative strands,

two stories told by the film, it is apparent that the alternation between

them forms ‘breaks’: it produces contrasts – and these contrasts

are visible. Indeed, I feel that today’s reality somehow is cool,

and more “matter of fact” than the reality experienced by Huang Ching-cheng,

the painter from Penghu.

Penghu, itself, and the time of

Huang’s growing up that we are asked to discover, has almost the peaceful

nostalgic flavor of some films made by Hou Hsiao-hsien. But it is also

that part of the ‘past’ told by the film where outdoor scenes most clearly

abound. As if, for some strange reason, what is farthest away is also the

reality that is closer than all others, to the filmmaker, and therefore,

via the film, to the audience as well. But it is close and warm,

a memory filled with mellow sunlight; not close and cool, technical, modern

and factual, as today’s reality.

A rural scene? Evacuation, during

WWII

And yet, the cool present depicted

in the film takes up a theme or rather, concern, inscribed so centrally

in the life of the painter which develops in front of our eyes, both in

Taiwan and the colonialist “motherland”: In both world’s, the painter’s

and the art restorer’s, the same passionate, urgent, serious quest for

beauty and for freedom is visible. We discover, throughout the film, how

it emerges in the life of the painter as the main driving force. And we

know that somehow it is present in the young woman who, in her own modest

way, is the brave protagonist who stubbornly confronts today’s drab,

yet glittering, globalized world. Both are perhaps IN A WAY outsiders,

almost strangers in their respective realms: they are calm, steady, determined

yet nonetheless passionate rebels: rebels in love, searchers of free relationships.

Breaking gently but in an entirely serious way with taboos - with traditions

of patriarchical authority, in the case of the painter; with the

conventional role of women as second to men, and giving in, bowing to their

wishes, listening to and heeding always their advice, in the case of today’s

beauty-searching, art-loving restaurateur.

Perhaps this is the decisive “reduplication”

in this movie – that it breathes a thirst for freedom, that it constructs

a structural relationship between two stories, the story of the frame and

the story of the narrated past, and that in both stories the respective

protogonist embodies, in his or her quest for beauty and for human emancipation,

a subversive yet quiet revolt. Perhap it is not by accident that in the

contemporary world we discover in this film, the protagonist is a woman.

April 13, 2011

|