| Azed

Yu

Feminist Films with Literary Touches: On Huang Yu-Shan’s

Films

Director Huang Yu-Shan is a teacher

that I have long admired and revered. From her, I see the passion, candidness

and sincerity that an image producer has. She manages to manifest the diversity

of a woman’s life with 24-frame images. And she dreams her movie dreams

in different positions: narrative movies like Autumn Tempest,

Twin

Bracelets, Peony Birds, Spring Cactus,

Portrait

of Restoring Light or documentaries like The Petrel Returns,

Chiang

Ching-Kao & Chiang Fong Liang,

Siu Shih-sian: The First

Woman Mayor in Taiwan, Siou Ze-lan: The First Woman Architect

in Taiwan, all show her hard working in this field. Now allow me

to crystallize the concept of “woman” with words, but let the images speak

for themselves.

Image Writing with Literary Touches

Huang is good at following a plot

of literary writing style to arrange her images in a narrative film. Images

permeating with symbols become a dominant motif of her films which are

titled accordingly. Pairs of peony birds symbolize birds of love; Wind

in Autumn Tempest serves as a metaphor for an ever changing

society and complicated romantic feelings. Twin bracelets are the token

for sisterhood. At the end of Autumn Tempest, the confused,

love-torn young man is blown into midair in a whirl of wind. This symbolizes

that a dubious relationship is cursed and entangled in a web of religious

and social conventions. In Peony Birds, Shu-cin in her coma

has visions of her father and sees her mother burning her self-portraits

in front of her father’s tomb. Her helpless face and self-portrait overlap.

Illustration of Woman

In her films, Huang likes to illustrate

woman’s exploration of erotic feelings in the depth of her soul. The woman

starts to care for herself, listening to her body’s needs. In Autumn

Tempest, Su-bi looks into the mirror and touches herself while

taking a shower. That symbolizes her desire or an outlet of her wants.

In Peony Birds, Shu-cin has a short hair-cut

which her boyfriend deems as the real her. Through the reflection in the

mirror, woman listens to her body’s needs, which is an important motif

in Huang’s narratives.

Woman has been rehabilitated by

Huang with the power of images. To rail against patriarchy, she highlights

the unfair treatment that woman has had. In Autumn Tempest,

Su-bi at the end has to get an abortion, but then she also refuses to go

back to her self-centered husband. In Twin Bracelets, Hui-hua

eventually commits suicide as a forceful way of protesting against patriarchy

and its values due to which she has been rejected. Although Siao-lan in

Spring

Cactus bravely fights for herself, unfortunately she becomes a

sacrificed woman working in the porn industry.

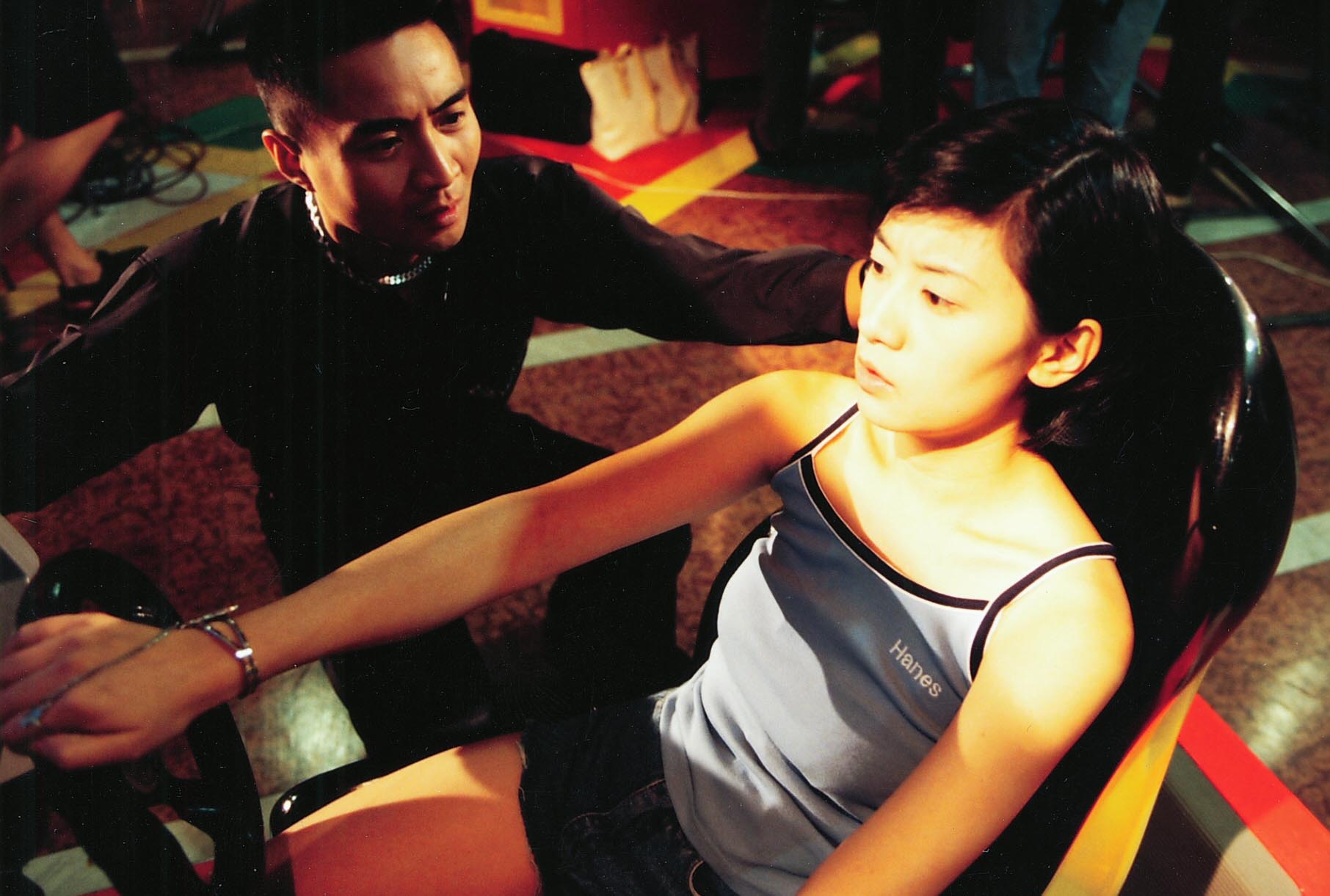

Siao-lan, the protagonist in

"Spring Cactus"

In Huang’s films, senior woman characters

are usually those who help to foster patriarchy. They educate their offspring

to be obedient and to accept the way things are. The housekeeper in charge

of the kitchen in Autumn Tempest teases or criticizes women

who don’t practice the expected “virtues”. The mother in Twin Bracelets

teaches her girls to sacrifice themselves in order to serve and obey man.

She even takes her daughter’s bride price to help the son marry his sweetheart.

A-Chan-jiuan’s mother in Peony Birds chooses to sacrifice

her daughter’s future to pay off the debt. The stepmother in Spring

Cactus despised Siao-lan because of her “occupation”. Therefore,

those who consolidate patriarchy are not necessarily men, but mothers or

a senior woman.

“Woman laboring” is a shared theme

of all her films. For instance, Su-bi in Autumn Tempest grows

vegetables in the temple almost non-stop. In Twin Bracelets,

those village women are always busy picking oysters or working in the kitchen.

In Peony Birds, A-Chan-jiuan and Shu-cin never stop working.

The woman characters in Huang’s films are always moving around restlessly

for their families, career, work and children.

Another theme is the suppression

of desires due to religion, ghosts or gods. In Autumn Tempest,

the hero and heroine are attracted to each other in a space where statues

of Buddha are always in sight. They represent the long existing confinement

or bondage of social value. Su-bi cannot let her feelings out under Buddha’s

gaze. In Twin Bracelets, Hui-hua and Siou-gu swear an oath

to be sisters forever before the Child-Birth Goddess who witnesses their

profound love. The Father in Spring Cactus symbolizes a god

and savior on earth. Religious belief is the only thing that brings peace

to Siao-lan.

Huang uses images and literary symbols

of different styles freely to uncover the inner world of a woman, making

the feelings of her woman characters deeper and more subtle. In her documentaries,

she takes the stance of humanism from different view points, showing her

concern for political or historical events and her advocacy of woman’s

rights.

A series of Huang’s works are going

to be shown in this year’s Kaohsiung Film Festival which is truly a rare

opportunity. Let us return to the world of images and indulge ourselves

in films to experience Taiwan’s female films—films of Huang Yu-shan.

Go back to AS

issue 12, Contents

|