| Andreas Weiland

(Re-)Discovering Zadkine

| It was when I visited a friend

in Rotterdam that I first saw a sculpture of Ossip Zadkine in the real.

The German Nazis, sending their bombers, had created a wasteland out of

downtown Rotterdam. The hustle and bustle that was so intrinsically a sign

of this pre-war quarter, made room for rubble. Later, after the war, a

large empty square filled part of the void left by the bombers. And soon,

the purposefully 'functional,' modern architecture of the time began to

occupy the margins of this, in many ways, sterile location. The glistening

reflections of the light of day, mirrored in the water of the windswept

harbor basin, are perhaps the most lively item here, apart from a few pedestrians

hurrying across the widy expanse of the square. |

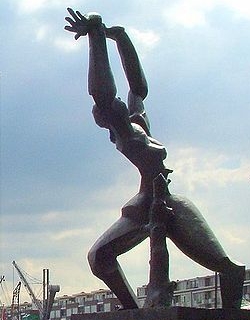

De verwoeste stad (1951-1953). Photo by Ziko

(2008)*

| It was here, almost at the edge

of the water, that Ossip Zadkine placed his work, The City Laid Waste

(De verwoeste stad). It was a work he began six years after the war,

in 1951 and completed in 1953.

The sculpture was also given the

alternative, perhaps initial title City Without Heart.

Does is refer to the fact that

the heart of Rotterdam, its historic center vanished when the bombs fell?

Is it primarily referring to the loss of lives - the lives of so

many inhabitants who lived and perished in this quarter? The aggression

that inflicted the wound - did it tear the heart out of living women and

men; did it cut a deep hole into their tormented bodies?

We see a human figure, its entire

body slanted, leaning backwards to an extent that is physiologically

impossible (without risking to actually fall and hit the ground). The figure

is lifting its arms towards the sky, as if warding off or hoping desparately

to ward off the terrible.

Part of photo by Ziko (2008)* |

The body of the figure is almost

unnaturally 'twisted.'

It lends movement, a strange dynamics

to the figure. As if it is already turning around and ready to flee.

Beginning, in fact, to flee.

The position of the disfigured hands

and the 'frozen' moment of frantic 'motion' they express, indicate helplessness.

The slanted head, its eyes facing

the sun, reveals the terror experienced.

Are these breasts I see? A voluminous

thigh? Is it, after all, a women who is facing death, who is facing the

German bombers? |

|

Photo by K. Siereveld (2007)*

Looking from another angle, we recognize

Zadkine's readiness to employ stilistic traits not unknown to cubism as

well as constructivism. It is befitting of a square lined by the kind of

architecture we see here. It is befitting to the 'theme' which also includes

the notion of 'industrialized war,' mechanized mass killing reliant on

modern industry, modern technology. The immense productive forces developed

by men in our age have been turned into destructive forces. If, under capitalism,

in its imperialist phase, man more than ever has been turned into a machine

that kills, if man eats man (as Lu Xun noted so aptly), then its is befitting

to show the victim as well in a way befitting to the spirit of the

time. Filled with human emotions such as deep anxiety, terror-stricken,

even, its limbs nonetheless are visible to us as constructive elements.

Curves, smooth, rounded edges are visible, though: they have replaced the

straight lines and sharp angles of 'pure' constructivism.

Holes appear. The void between the

outstretched arms that flows into the sky. The emptiness between the twisted

legs that is formed by these legs and the ground they undoubtedly touch.

Yes, these legs that project a sense of 'standing there,'

facing something, and of 'turning,' that is to say, of the

beginning movement of flight, also form a hole between themselves and the

earth. The third hole or opening of this sculpture is the most irritating,

and even scary. We see the sky through the slit that has been ripped open,

in this human body. Is it the letal wound, suffered at the very moment

when the imminent danger of death was recognized? Do we witness the moment

of dying? A dying person facing the sun, the blue of the sky, the arriving

bombers, the bombs dropped? We who are facing the sky at this very location

where so many died, where so many bones are perhaps remaining unearthed

forever, transformed as they were into ashes and dust and pain, we are

for a moment in the position of the people who perished. Looking up, up

to our sister, our brother, a fellow human being, tormented, suffering,

because of war. |

Photo by Rogier Bos (2005?)*

Photo by F. Eveleens (2007)*

|

|

Zadkine's 'Prometheus' was created

in 1954 out of a tree-trunk. It was subsequently cast in bronze by the

artist. The sculpture was acquired by the 'Municipal and University Library'

of Frankfurt in 1965.

A Frankfurt art critic, Petra Schwerdtner, noted in 2001:

"One hardly recognizes a realistic,

anatomical order in his figures. And yet, they remain attached to reality.

[...]

Larger than life, this bronze

figure,

Prometheus, stands in front of a concrete wall. [...] Zadkine's

Prometheus

strikes

us as enigmatic and mystical, due to his two faces. Looking at it frontally,

we meet the look of two displaced eyes, and note the mouth and nose which

the artist has scratched into the material.

With long strides, his wide,

flowing robe trailing him, the bringer of fire and founder of culture

hurries towards the onlooker and, at the same time, past him. Into the

room where visitors of the library have access to comprehensive knowledge

[...]. The front side of the figure is dominated by fire. Prometheus isn't

carrying the blazing flames in front of him but he is connected with them.

Here, the Titan is not only a mediator of art and culture; he has caught

fire himself. He is an inspired, creative being liberated by art. As transmitter

of the fire message, he attempts to draw the onlooker with him, asking

him to follow his example.

Parallel ideas can

be found in the work of Goethe, and thus somebody Zadkine directly refers

to, but also in the work of Joseph Beuys, 'Every man is an artist.' By

way of these words, the modern Prometheus appeals to the creative potential

in every one of us. [...] 'Choose art, that is to say, choose youself!

All of you! Every one of you!' [...]

(Petra Schwerdner, "Ossip Zadkines

'Prometheus' in der Unibibliothek ist Feuer und Flamme", in: Frankfurter

Rundschau, Aug. 14, 2001, p.32)(*)

(*)"Eine

realistische, anatomische Ordnung erkennt man in seinen Figuren kaum, dennoch

bleiben sie der Wirklichkeit verbunden. [...]

Vor einer Betonwand steht überlebensgroß

die Bronzefigur Prometheus.[...] Rätselhaft und mystisch wirkt

Zadkines Prometheus durch seine zwei Gesichter. Von vorn begegnet man dem

Blick zweier räumlich versetzter Augen, Mund und Nase, die der Künstler

in das Material eingeritzt hat. Mit weit nach hinten wehendem Gewand

und weit ausholendem Schritt eilt der Feuerbringer und Kulturstifter auf

den Betrachter zu und zugleich an ihm vorbei. Hinein in den Raum, in dem

Bibliotheksbesuchern [...] umfassendes Wissen zugänglich ist.

Die Vorderfront der Figur wird vom Feuer

beherrscht. Prometheus trägt

die lodernden

Flammen nicht nur vor sich her,

sondern ist mit ihnen verbunden.

Der Titan ist hier nicht nur

Kunst-

und Kulturvermittler, sondern

er hat

selbst Feuer gefangen. Er ist

ein durch die

Kunst befreites, schöpferisch-kreatives

Wesen. Als Überbringer

dieser |

|

|

Prometheus. Photo by Peng (talk).*

Feuerbotschaft versucht er, den

Betrachter

mit sich zu ziehen und fordert

ihn auf,

seinem Beispiel zu folgen.

Parallele Gedanken finden sich

bei Goethe, auf den sich Zadkine direkt bezieht, und im Werk von Joseph

Beuys. 'Jeder Mensch ist ein Künstler.' Damit appelliert der moderne

Prometheus an das kreative Potential, das jeder Einzelne von uns besitzt.

[...] "

"Wählt die Kunst, das heißt

Euch

selbst! Alle! Jeder!' [...]"

(Petra Schwerdner, "Ossip

Zadkines 'Prometheus' in der Unibibliothek ist Feuer und Flamme", in:

Frankfurter Rundschau, Aug. 14, 2001, p.32) |

|

, |

|

The park of the 'sculpture museum' in the small German

town of Marl (a place formerly dominated by coal mines, just as so many

other towns in the Ruhr District), features a striking work of Zadkine

called the 'Great Orpheus' (Grosser Orpheus). According to one source,

the sculpture was initially created in 1948, but perhaps in a different

material (stone, or wood). The 'Great Orpheus' in Marl was

cast in 1956.

The influence of Zadkine's earlier formal orientation

which was impregnated by Cubist aesthetics can still be felt. The human

body has been 'segmented'; it isn't a 'whole' but an ensemble of 'parts.'

As in the sculpture of a human figure that evokes those who faced (and,

in many cases perished in) the Nazi German air raid, i.e. in

The City

Laid Waste, a void opens in the human body. In its chest, that is.

Does it privilege essence over physical 'materiality'? Does it enhance

the dynamics, the movement that is to be present, in a solid sculpture

- a bronze? We remember, I think, the strides taken by Zadkine's Prometheus.

There, too, the felt presence of movement was important to the artist.

In The City Laid Waste, the body of the woman that appears to us

when we see the sculpture is about to turn around and flee. The extremely

slanted position of the sculpture suggest destabilization, precarity, the

threat felt, the imminent fall.

Here, in the garden, amid trees, positioned in nature,

in a grove, so to speak, Orpheus is playing his lyre. To play means to

move. At least it mean to move the hands, the fingers. But perhaps that

does echo in the upper part of the body, as well. Whereas the feet of the

player need to be standing solidly on the ground.

The head stands out in a clear, precise way. The singer

has opened his mouth, accompanying the tune of the lyre with his song.

The eyes - are they shut, or almost so? Concentrated or rather, immersed

in his playing and singing, he doesn't let his eyes wander. Or stare at

something.

The positions of the arms reflect the need to hold the

lyre properly while playing. There is nothing gratuitious in them. The

left arm is raised; it forms an angle of about 90 degrees. The right arm

is in a slightly curved and a lower position. The tension between the positions

of both arms is clearly determined by the playing and in a way, the hands

and the mouth form an invisible but intuitively sensed 'connecting

line.' It reflects, I would say, the 'oneness' of the act of playing and

singing.

In spite of what I said about a necessity to be firmly

anchored while playing, I ask myself, noticing the position of the feet,

whether Orpheus isn't slowly walking? Moving on, among the trees, ever

so lightly, slightly, while he sings and plays...

The legs support that assumption. While Orpheus has turned

the head toward us, he seem to move sideways.

The legs, incidentally, are showing soft, smooth lines

and a slightly curved surface. Their segmentation is visible - but only

as a 'somewhat hinted at', mild fragmentation, at least when the figure

is perceived in the way of the first photograph. The second one reveals,

in the case of the left leg, the hiatus, the jarring way of joining its

parts at the knee - a much clearer break with any (even if only faintly)

'naturalistic' way of modeling the human body than we note in the case

of the other, the right leg.

|

Link to

another image in: www.schwarzaufweiss.de Link to

another image in: www.schwarzaufweiss.de

Great Orpheus (Grosser Orpheus)

Photo by Gerardus (taken in 2008)*

It is also in this second photograph that the ripped-open

chest becomes much more visible. In the other photo, that is to say, from

the location where it was taken, we can only 'guess' or 'surmise' the opened

chest and if we look carefully, it seems to us perhaps that we are permitted

to look inside the human body. The movement of the line inscribed into

the right leg is carried upward, way above the hips and merges with and

is continued by the curved plane that forms the figures 'back'. In fact,

looking from the front, we are allowed to see the 'inside' of Orpheus'

back. It is as if we were looking into an elongated, open bowl, seeing

its bottom. And at the same time, a clearly structured surface stands out

in front of it. Ribs? Or a part of the musical instrument?

Whereas the first photo gives us a certainly 'deformed'

but nonetheless recognizable semblance of a male figure, this semblance

fades in the second photo, at least from the waist upward, if we exempt

the bent arm. Isn't this strange? A way of 'making' our perception feel

(or appear) 'strange' to us? A way of making the object of our perception

'strange'? Yes, certainly. Though it has perhaps very little to do with

Brechtian Verfremdung [making-strange]... For Brecht, the insight

that sprang from 'hearing' something in a way that placed the ordinarily

'well-known' (as we mistakenly thought) in a new light was what mattered

above all. And Zadkine? Does he aim at emotions rather than thought? Or

perhaps both? We don't hear words, don't watch a play; we see a visual,

three-dimensional work of art. What does it 'tell' us? That the singer,

Orpheus, isn't whole and harmonious anymore because he has seen the horrors

of a century?

We may have to ask ourselves this question.

Picasso's fragmented, torn, dissected, re-combined human

forms, present in two-dimensional works, already echoed the disaster of

the approaching and then, the suffered war of 1914-18. Europe had become

a place of skulls, of murderous confrontation. After 1945, a new, more

barbaric experience had been added and Zadkine has chosen, has been compelled

to become a concious witness of it.

|

*

Great Orpheus

(Grosser Orpheus).

photo by Daniel Ulrich (taken in

2005)* |

In the same year that 'Great

Orpheus' was cast in bronze, Zadkine did a sculpture entitled 'Hommage

à van Gogh'. It can be seen in the Parc Van Gogh, in Auvers-sur-Oise.

In contrast to 'Great Orpheus'

(which really is closer to the spirit of 1948), the sculpture dedicated

to the menory of van Gogh strikes many of us as almost conventional, perhaps.

The organic is very prevalent in the bark-like surface structure. But the

tension that goes with it in 'L'arbre de vie,' another work showing

a texture that reminds me of the bark of a tree, is missing here. Or at

least I fail to notice it.

What I notice is the expressive

face; the face of a man facing resistance. Confronting the world, the Others,

with great seriousness, courage, skepticism, probably in the way of someone

thrown back onto himself. And isn't the upper part of the body, as well

as the face, reclining backwards, ever so slightly? A small, but revealing

nuance.

His tools, the tools of a painter,

the easel above all that allows him to paint outdoors instead of in a studio

(a fact as radical at his time as it was when film directors in Hollywood,

like Henry Ford, left the studio in order to shoot their films in the open

countryside?), they are tools that appear to me like his pile of weapons,

worn on the back. And the crossed leather belts visible on his chest might

remind any one familiar with John Ford's movies of belts that are full

of ammunition. Isn't he appearing here, like James Fenimore Cooper's trapper,

Leatherstockings, as a man who just stepped out of the immense forest?

Standing, watchfully, intent, in the middle of a lighting. A lonely man,

I thought, like all trappers and pathfinders. All those who are traversing

as yet unknown territories. |

Van Gogh, Vincent Van Gogh Park in Auvers-sur-Oise.

Photo by Jean-no ? (2005?)*

L'arbre de la vie (1957)

The tree of life (L'arbre

de vie) is a sculpture completed by

Zadkine in 1957.

A rough, very organic, bark-like surface structure, not unlike that

witnessed in some sculptures of Giacometti, is characteristic of the work.

It is present in the surface of the 'tree-trunk;' it is covering

the skin of its 'branches' that are metamorphosing into human arms; but

it can also be discovered in the case of a pair of wild, skinny, nasty

dogs at the foot of the 'tree,' furiously barking at something way

up high.

Perhaps, apart from the balanced

proportions, this common surface structure is one of the elements that

gives the work unity. The other 'element' that gives this work unity is

the after-image it leaves on our inner, mental 'retina' -

that of a religious object, a candelabra. Instead of its candles, we see

raised hands. The branches of the 'tree,' the candle-bearing arms

of the candelabra, are repeating in a way the well-known form so familiar

to those who were raised in the Mosaic faith. They are fairly thin, and

the raised hands therefore rest on other 'arms,' as well: not the curving

ones that branch off the trunk further below - but thicker, stronger, horizontal

ones. Strange addition to the 'after-image' that forced itself on me, they

leave me with a strong impression. It is as if the trunk divides its force

of growth, suddenly continuing this growth both leftward and towards the

right. Why? Because the hands and arms need to be joined. They need to

join; they need to link up. A strong expression of togetherness,

of human solidarity. I think of survivors, united by brotherhood,

by sisterly ways of mutual help, of strong dedication to a human project.

And the dogs, below? Yesterday, they were the fascist henchmen, the murderers

bringing death to those transported to the sites of slave labor, to the

children, the women and men in the death camps. Celan spoke of the smoke

that was left of them. Zadkine speaks of the resistance of the living who,

victims once, have survived.

The strength of their solidarity,

this sculpture seems to say, will resist all assailants. And they will

survive. |

*

You can see a good photo of the "Tree of Life"

if you visit the Tjerk-Wiegersma website:

Zadkine, L' arbre de la vie

http://www.tjerk-wiegersma.com/artwork/view/99

Ossip Zadkine (Russian/French, 1890-1967)

L'arbre de vie, 1957

72 x 74 x 51 cm

28.3 x 29.1 x 20.1 inches

Bronze

Signed and numbered 2/5

Foundry: Modern Art Foundry, NY

Commissioned by the American architect

Daniel Schwartzman in 1957 |

* |

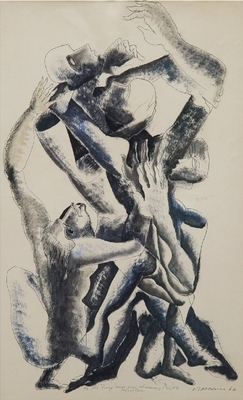

In 1946, Ossip Zadkine had done a gouache

he called 'La Forêt Humaine' (The Human Forest). Perhaps a

title like 'Human Jungle' would have been too revealing, too outspoken.

The war was just over. The suffering, the millions who were dead now, still

fresh in the mind. And for Zadkine as so many others, what had happened

to the member of the Maquis caught by the Nazis, to villagers like those

in Oradour, to Jews and Communists, Social Democrats and Homosexuals, Sinti

and Roma in the death camps, was something that was worse, more disconcerting,

perhaps more traumatic than any bloody battle of armies because it was

even more hideous, more terrible.

*

La Forêt Humaine, 1946

Gouache, India ink and wash |

The work shows that Zadkine has

returned from starkly abstract, geometric forms to flowing, organic lines.

A few, nearly straight, diagonal lines that are strongly visible are the

only trace left of his earlier formal preoccupation. They are in part covered

by other forms, and the overall impression is that of a maze, a tangle,

a confused, in places perhaps slightly loose yet in its effect terrible

knot of people. We see elongated hands and arms, as if beckoning, crying

out, asking to be saved, waving and calling for help. We see, dimly visible,

a head, a bald head - that of a victim, a prisoner. It must be the head

of the beckoning man. Is he tied to beams, wooden beams that form a cross

- like that Jew from Galilee was tied to them, according to the narrations

of the Christians, the Jew-Haters? No, I assure you, not all

of them were or are jew-haters - I know it. And yet, the anti-judaism,

wasn't it inscribed into their religious statements, for century after

century? And exploded into something new when racism seemed to conquer

a 'scientific' language, in defense and supposed justification of its obscenities?

The obscenity is present in this work. It is present in the form

of a naked woman who attempts to take hold of the crucified man, the tortured

one, the victim. A pig's face stares at the victim. The face of evil? The

face of fascism?

No, this, to my mind, is hardly

about sex. Or gender. Not about "man and woman." It is about the beast.

The perverse, obscene beast of fascism. And about the men and women (perhaps,

men, above all) who desired a 'leader' and who were ready to obey the commands

of a brutal, barbaric State.

Source of image: :

http://www.whitfordfineart.com/pages/single/2335/ossip_

zadkine_la_for%EAt_humaine.html |

In 1960, Zadkine realized a sculpture

bearing the same title and, in fact, the theme suggested by it in the gouache

seems to be taken up indeed, although in a different formal (i.e. aesthetic)

language. I see a mechanical, mechanized, "machine man." Limbs, without

doubt. The bent legs of a seated human being. His left arm. Another, smaller

arm, perhaps that of a child, is stretched out toward him, as if imploring.

A hand, perhaps - no, probably - that of the large man, the "machine man"

(as I suggested, quite hurriedly) holds something. A weapon? And the horns

that pierce the light-grey air of the sky, are they too indicative of a

world filled with too many weapons?

|

The Human Forest / La forêt humaine (1960),

sculpture

in the garden of the Van Leer Institute,Talbiya,

Jerusalem

Excerpt of photo by Deror Avi.*

|

|

|

| 'La demeure humaine' (The Human Habitat) was created

in 1963/64. The sculpture can be seen in Amsterdam, Holland. In this work

of tangled yet faintly geometric metal 'beams' (some of them bent into

round curves, but most of them fairly straight), a vast house can be seen

and in it, in fact, on the top, two relatively tiny human beings. It is

as if makers of houses have lost all sense of human proportions, creating

vast 'machines' intended as habitats. The Germans have an adequate word

for it, Wohnmaschinen. 'Dwelling machines,' or 'machines for living'

are clumsy terms, by comparison. To my mind, the sculpture reveals Zadkine

again as a critical, committed artist, with a sharp sense for what is wrong

in our world today, a sense which is also revealing another trait of the

artist: his sense of 'humor.' A black humor. |

lLa demeure humaine (The human habitat) (in Amsterdam) (1963/64)

Photo by Pjotr P. (2009)*

* All photos marked with an asterisk are licensed by their authors

according to "GNU" licenses

(creative commons).

IMPORTANT NOTE:

The photo of L'arbre de la vie (1957) is copyright material and

so is the photo of the gouache

La Forêt Humaine (1946).

They have been included for art scientific purposes because their presence

is vital for the discussion of Zadkine's work in this article.

Links to the URL-site where these two photos appear have been included

but the size of the gouache shown there is too small to recognize all the

details discussed.

The photo of L'arbre de la vie that is included in this non-commercial,

non-profit art journal is included for the purpose of orientation only.

It is very small but the photo offered by the Tjerk-Wiegersma site which

is larger can be accessed by way of the link.

We thank the copyright owners for being able to use these two digitalized

images. |

|