| Andreas Weiland

THE SCULPTURES OF ALBERTO GIACOMETTI

Seen in the Kunsthal Rotterdam (Giacometti Exhibition,

October 18, 2008 – February 8, 2009)

There are few chances these days for most of us, it seems,

to see a large number of works by Giacometti assembled under one roof.

Perhaps this is a good reason to come and see his work

in its larger context. And perhaps it also provides a rare opportunity

to reflect on it anew.

I will take as a starting point one of his very remarkable

‘early’ sculptures, The Couple (Het paar), a 1927 sculpture that

was finally cast in bronze after the war, in 1955.

The Couple (1927) The Couple (1927)

Here, the influence of African sculpture seems to be unmistakably

present, as it was also in some of the works of Picasso dating back to

this period. Giacometti’s ‘Couple’ achieves a balance that is extraordinary

in its quiet, almost natural unobtrusiveness, calmness, and perfect simplicity.

It ‘rests’ in itself, achieving sheer presence. It projects a sense of

perfect (‘natural’) harmony. The great simplicity of the abstraction (or

should I say, stylization [Stilisierung]?) achieved astounds; what

I perceive here is the symbolization of the human face, choosing two different

forms of expression: the left one is an oval form that culminates in a

single point (though not sharply); the right one, on the other hand, is

a form that is determined by almost straight lines of which the longer,

almost vertical ones are not running parallel, however: they are slightly

more apart at the bottom than they are at the top. I cannot help noticing

the displaced eyes, the transformed shape of the mouth, the stylized indication

of cheekbones, the (by and large) flat surface of each face.

The preceding year, 1926, may have seen already the production

of a sculpture simply named ‘Figure’(Figuur; c. 1926) that combined (and

thus was constructed by making use of) different geometric bodies: cubes,

an L-shaped corpus, elements that look like a barrel or rather, a cylinder.

The overall impression, to me, was that of a sculpture reminiscent of Pre-Columbian

Mezo-American (and perhaps also South American) art.

Yet another composition of that era, a bronze sculpture

dated c.1926-27, can be described as a Cubist composition.

1927.jpg) Composition

(man), 1927 [not the work discussed - but 'similar'] Composition

(man), 1927 [not the work discussed - but 'similar']

It rests solidly in itself but shows also a considerable

internal dynamics. Two main components can be identified. One is a block

that is almost a cube; the other is a cylinder. As the axis of the cylinder

isn’t vertical whereas the delimitations of the cube are fairly horizontal

and vertical, it was unavoidable that the dynamics (or formal tension)

mentioned above would result. Frank Gehry has used this approach in Bilbao

and also in the construction of the MARTa in Herford. But the lines emphasized

by Gehry’s architectural composition appear to us as straight and sharp

and abstract whereas the charm or magic and certainly the aesthetic fascination

of Giacometti’s composition hinges on the fact that the ‘cornering’ lines

(or delimitations) of this sculpture aren’t smooth and truly straight,

and that they do not run parallel to each other in any exact sense of that

word. Therefore, the charm of the sculpture can be likened to that of a

windswept shack with annexes or extensions that has not seen the involvement

of an architect but that is truly the work of a user or dweller who constructed

his dwelling based on intuition and practical experience.

The ‘Head of [Giacometti’s]Mother’

(1927), a sculpture making use of plaster (i.e. gypsum) as its material,

is remarkable because of its reduced volume, a volume that is only hinted

at, bringing forth little more than a relief. There is a remarkable gentleness

of the facial shape, of its outlines that I note, and more generally speaking,

a quiet but very present tenderness embodied in the entire form. The facial

surface is scratched ever so lightly.

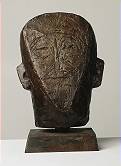

In contrast, the ‘Head of [Giacometti’s]Father’

(1927/30), also made of plaster, is edgy, sturdy, and characteristically

shows a flat facial surface delimitated sideways by straight though not

parallel lines.

Head of Father (1927/30) Head of Father (1927/30)

As if that in itself was not extremely expressive already,

many heavy scratches mark this flat facial surface, indicating facial features.

Almost during the same period, another sculpture, called

‘Hanging Ball’ (Hangende bal; c.1930-31) originated. It is made of plaster

and metal. To me it is like a poetic dream. It seems weightless, an image

of the sun and the moon touching. The moon is a flying ship or boat, hovering

in the air, faintly touching the ‘water’ underneath (that is to say, the

uneven base of the sculpture) with the tip of its bow or fore-end. Almost

unnoticeably so, I would say. The sun is a ball, suspended in mid-air.

And it’s touching the half-moon’s ‘boat’ ever so lightly…

All of this is a miraculous composition: its white presence

alight in front of our gazing, surprised, amazed eyes.

It is perhaps from the same period that the next sculpture

may date. I would describe it as a horn, an isolated horn separate from

the animal to which it once belonged. But it is also a horn that at the

end opposite its tip shows the fingers of a fist. This circumstance truly

turns it into a strangely surreal object, I feel. I may add that the surface

of this sculpture is not smooth and polished but slightly uneven. But it

is perhaps as close to the relatively smooth surface of traditional bronze

sculpture as Giacometti ever got. The tendency was to strive away from

it, make it more organic, rougher, more fragmentary, full of ravines and

protruding, piercing areas.

This can be seen when we look at ‘The Leg’ (Het been;

1958), a sculpture that shows an isolated, skinny leg with a surface so

rough and organic that it makes me think of a dry branch of a tree that

it could have been removed from. This clearly constitutes a reaction, a

displacement, a counter-design, also a counter-project or Gegenentwurf

opposed to more classical sculpture with its polished, smooth, idealized

surfaces. It’s enough to think of the sculptures of Jean Arp to understand

the différence aimed at by Giacometti.

This attempt to depart from the idealization of the human

form implicit in a smooth surface is already visible, though in a

less extreme way, in a work like the ‘Bust of Diego’, Alberto’s brother

(done in 1951), a bronze sculpture remarkable not only because of the earnest

face we see but also the rough surface of the chest.

Bust of Diego (1951) Bust of Diego (1951)

There were other ways to de-automatize sculpture and break

with conventions. For instance, by relying on tiny, seemingly ‘unimportant’

plaster sculptures, placed on a small, very ordinary brick. ‘Annette’,

done in c. 1946, a small sculpture consisting of painted plaster and placed

on such a brick, is a good example. To my mind, this is a love poem, delicate,

full of tenderness. I am enchanted by the painted line of the mouth, the

hinted at, sketchy indication of the eyes, the wild beauty of the hair,

the astonishment and confusion in her face and great presence of her seemingly

frail and tender body. So small! And yet a major work of art, an extraordinary

product of sharp observation, empathy, intuition and an acute artistic

imagination!

‘Head on a rod’(Hoofd op en stang; done in 1947) is a

sculpture that confronts the viewer with a pure urge to 'express', perceived

– on the one hand – in an expressive face, sensed – on the other hand –

in the reduction of the remaining parts of the body to a mere rod, a thin

and longish piece of metal, with an uneven surface.

‘The Cabbage’ (or De Kool; first version / eerste

versie 1949-50) is a bronze sculpture consisting of two separated metal

layers that form the base, and a frame of thin wire that constructs a universe

above it, a universe that assumes the shape of a virtual cube. Within

this ‘universe,’ two figures exist. The one is a thin man almost like the

figures drawn by the Swiss graffiti artist, Naeggeli. Its face is the only

part that was allowed to have a certain appearance of volume, the rest

is just wire with a rough surface, in the shape of lines that are never

straight (or curved in an even fashion).

This figure of a man has its legs wide apart, and the

outstretched arms touch the thin wire of the virtual cube that form the

delimitation of the entire sculpture.

I see in it the ‘crucified man’ who suffered war and persecution

and who emerged, an anguished and lone survivor, from concentration camps.

It’s the head, its face, that is central because its expressivity stands

out. Above and beyond this, we notice the de-embodiment (or Entkoerperlichung)

of the body. Seeing it, it is impossible not to think of starved human

beings liberated from the camps.

The second figure inserted into the universe of this

sculpture is much smaller; it consists of a relatively big head mounted

on a noteworthy throat that sits directly on the ground, growing from it

like a ‘cabbage’. (Therefore, ‘De Kool”?)

The ‘Bust of a man’ (Buste van een man) done

in 1956 is, again, a bronze sculpture of Diego. Like other works realized

by the artist after the war, it was done d'après nature (“after

nature”), as they say in France and in Giacometti's native Switzerland.

Alberto’s brother Diego was sitting as a model in front of the artist when

the work was done; a break with the dominant reliance on the inner eye,

the imagination that was so clearly prevalent in his earlier work, and

especially during the phase of his openly Surrealist orientation that was

formally ended in 1934.

The part of the sculpture that represents the shoulder

and chest shows a rough, intensely (if not severely) worked on, seemingly

organic surface. At the same time, the upper part of the human body has

lost its conventional human shape; it has been transformed into a mountain

from which the head springs forth. This reminds me of enigmatic Chinese

Buddhist paintings or sculptures. We may wonder whether the pre-war attachment

to surrealism still shows through. At any rate, it is an irritating work

of art, an immensily expressive way of grasping the lived experience inscribed

into a specific body, that of his brother who was sitting in front of him...

The work referred to by Giacometti as ‘Stele III’

(1958), a sculpture made of plaster, shows again a large, expressive face.

The mountain that we discovered as an important part of the ‘Bust of a

man’ done two years earlier has become a shoulder plus chest, again. Or

a bouquet of flowers – a dense section of a hedge that consists of bulging

flowers.

‘Large head’ (Grote hoofd; c. 1958) is a bronze

with an expressive head the surface of which has been scratched intensely.

The upper part of the body appears like a bronze tree, with the thick bulge

typical of willows the branches of which have been cut short, again and

again.

Encountering the bronze sculpture titled ‘Tall Woman

IV’ (Grote vrouw IV; 1960-61), you look up to this face more than 2

meters above you. It is not only the face of this sculpture that

‘expresses’ something. The same is true of the body, too. It expresses

a posture or attitude vis-à-vis life, a meaning of this existence.

Its proportions seem only to exist in order to express, to ‘overdo’ and

thus make visible, this stance. The choice of a way of existing that has

been grasped.

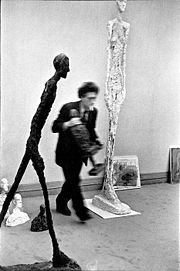

When I confront the ‘Running man’ (‘Lopende man’),

a bronze done in 1960, in a way it is above all the head, the face that

matters. The thin remainder of the body is ‘just’ energy, dedication to

forward movement that has become almost devoid of whatever is ‘body substance’:

yes, mass instead has been almost entirely transformed into energy, a possible

transformation that Einstein had recognized (or ‘predicted’).

'Running

Man' and Giacometti (photo by Cartier-Bresson) 'Running

Man' and Giacometti (photo by Cartier-Bresson)

‘Tall woman’ (‘Grote vrouw’; 1960), another bronze,

shows a similar trend of Entkoerperlichung (de-embodiment) or loss

of corporal substance, and in that sense, seems to present a diminished

‘reality'. But this loss is at the same time gain, and what is gained is

intensity. In terms of expressivity, we note the face and especially the

hands – the way they cling to the body, touch and hold on to the flanks

of extremely thin legs, in gauche or embarrassed fashion. It is

this, in all likelihood, unconscious gesture that matters. Instead

of the body as matter, as meat, as flesh, the body is present as

the site of experience, of confrontation with the world, with Others. Isn't

it revealed, here, as a place of awkwardness, vis à vis the Others,

perhaps even of suffering, but also of a quiet resistance?

Women with Fractured Shoulder

(c. 1958-59) - not the work discussed Women with Fractured Shoulder

(c. 1958-59) - not the work discussed

but showing the discussed emphasis on 'de-embodiment', of 'reduction'

The ‘Woman with cart’ (‘Vrouw met kar’; c. 1945),

a sculpture made of plaster, is seen by me as a ‘princess’ – a tender,

vulnerable, young girl, the body a bit thin it seems but this thinness

is not extremely overdone. The surface of the sculpture is very rough,

very uneven, very organic. I notice the whiteness of the light reflected

by this surface and the shaded parts.

‘Tall woman, sitting’(‘Grote vrouw zittend’; 1958)

is another sculpture portraying Alberto Giacometti’s wife, Annette. The

way I see it, this bronze sculpture marks a return to the tender perception

of a human being, not only of the face but the entire upper part and lap

up to the knees. The rough, tree-like, ‘wavy’ or irregular surface of the

sculpture bears the mark of expressive scratches.

The ‘Bust of Annette IV’ (‘Buste van Annette IV;

1962) is a bronze sculpture that features a wide-awake, sceptically looking,

or perhaps anticipative and expectant face. The upper part of the female

body looks like a windswept tree in a Classical Chinese painting, thus

stressing the fragmentary character of the way this part of the body has

been formed. This fragmentary character enhances the expressiveness

of the work, lending it a considerable force, an undeniable inner or ‘psychic’

(e)motion.

Another work of that year is featuring again the wife

of the artist. It is called the ‘Bust of Annette’ (‘Buste van Annette

[of Venetië]; 1962). I cannot help noticing the earnest face.

And in the case of this work, the upper part of the body is given in a

less fragmentary way.

The ‘Bust of Annette VIII ’ (Buste van Annette

VIII; 1962) is again a bronze sculpture. The face of the woman shown strikes

me as curious and at the same time, rather earnest while the ‘rump’ has

been turned into a tree trunk, I feel.

The entire series of busts of his wife Annette is perhaps

read with so much attention by me because I’m fascinated by the changing

facial expression observable over time and obviously registered and represented

in a sensitive way by the artist. In the case of the work entitled ‘Bust

of Annette IX’ (Buste van Annette IX) that was done in 1964, the face

of the woman shown appears to me as patient, also as sad. The shoulders

and the chest appear as frail, they have been realized in sketchy way.

The ‘Bust of Annette X’ (Buste van Annette X),

another work with the same subject matter that was done in 1965 and

that is the last one, I think, of this series shown in the Rotterdam Kunsthal

exhibition, shows an Annette that seems to be sad, despaired, full of anguish

and fear of loss. And the chest of the woman shown – how can I describe

it if not as an extreme fragment, torn at, ripped, partial, with pieces,

edges, abruptly cut off?

The form matters, obviously: transporting signs of psychic

involvement, psychic tremor if not disturbance.

It may be a private reading but a legitimate one, I think,

given the extraordinary emotionality of the formal language chosen.

The "thin, elongated forms" discussed are very

apparent in works like Woman of Venice II

and Three Men Walking.

Such "thin" sculptures imply a reading of the

human body that focuses on 'attitudes'

(Haltungen) and on lived experiences (le vécu).

They are 'portraits' of thinking and feeling

human people facing the 'Other' outside

the sculpture. |

Woman of Venice

II Woman of Venice

II |

.jpg) |

Walking people? Yes - but even more so, three people who relate to each

other, who "meet" and "confront" each other and turn away from each other..

Three Men Walking (1949) |

Instead of continuing to move towards extremely thin,

elongated forms, subverting in this way older classical as well as modern

classical sculpture, Giacometti in the early to mid-60s arrived at another

way of breaking with convention and heightening the expressivity of his

sculptures: it was the use of the rough (in fact, "roughened"), barky surface

chosen to represent the skin surface of the human body (a technique,

in fact, an approach, that he had discovered at an earlier moment

of his artistic development). And it was, to an even greater degree, the

rough and almost violent way of turning the upper part, the shoulders and

chest of the human bodies he fashioned in bronze, into ‘torn at’ matter,

into substance that had pieces and edges ripped frantically away.

Was this a triumph of essence, of expressivity, over matter? I don’t think

so. The expressivity was always rooted, it was always anchored in matter,

in the human body that was cast, by the artist, as a bronze sculpture.

The body itself WAS expression, it was expressivity. And this because life

gnawed at it and left its traces. Because the body resisted the force of

things and carried away bruises. Because it transformed itself by the act

of living, by the choices made, the emotions felt and admitted or denied,

the thoughts thought or suppressed, the ideas admitted and embraced or

refuted and denied. The deeds done, or not done, or done half-heartedly.

The project of living itself was taking shape, was assuming form, in the

human bodies portrayed. And the sculptures reflected it, the artist sensed,

discovered and formed it. It is this ability that makes Giacometti such

an extremely important contemporary artist. Of the last, and because of

the vitality and continuing emotive presence of his work, also of this,

the 21st century.

Rotterdam, January 25, 2009

Fair use of images in this article on Alberto

Giacometti

(1:) This is an academic, i.e. "[art-]scientific"

(or 'kunstwissenschaftliche") discussion of the work of a relevant artist

that can not fully make its point without presenting "visual material"

to substantiate the point made.

(2:) Though the images presented

are subject to copyright, their use is covered by the U.S. fair use laws

because:

These are historically significant

works that could not be conveyed in words.

Inclusion in this article (that

appears in a non-commercial, non-profit art journal edited or co-ordinated

by non-paid editors) is for information, education, and analysis only.

Their inclusion in the article

adds significantly to the article because it shows major types of work

produced by the artist.

The images are low resolution

copies of the original works and would be unlikely to impact sales of prints

or be usable as a desktop backdrop.

They are not replaceable with an

uncopyrighted or freely copyrighted image of comparable educational value.

|