| J. Weidenfels

Hrdlicka, Sculptor, Citoyen

| 1

Yes, some day we will perhaps

take note. Take note that there was a great humanist and a vibrant artist

living in Vienna in the decades after the big war who was ready to

combat the spectre of fascism when almost everybody thought fascism was

dead. And when so many of us (artists included, but especially critics,

politicians, and the 'educated public') thought that art should turn back

to itself again, rather than dirtying itself with 'commitment.'

Alfred Hrdlicka must have been

one of those few people who hardly thought that fascism was really vanquished

for good. Vanquished regardless of how much xenophobia and racism we encounter

in Europe today. Regardless of all the old people in Germany - and in Austria,

as well - who still say, "After all, Hitler wasn't that bad..."

Yes it's true. For a long time

they ducked, they didn't raise their head. They cowered and remained quiet

and muttered and nagged at home only. In public, they'd be not quite that

outspoken. And if so, they would add, "If he just hadn't started that damned

war."

Haven't you heard that phrase,

ever? Then, where are you living? And why don't you open your ears? You

might perhaps hear them adding another "if". An "if" that is intended to

ward off all criticism that they are anti-semitic. Anti-Jewish. So they

say, pronouncing it carefully, "...and if he hadn't killed the Jews."

But isn't it crazy? Do they want

to say that Hitler had killed them all in person, six million or more people?

Killed them without the collaboration of a bureaucracy, the help of police,

army, secret service? The supportive role of diplomats? The often nodding

approval of citizens who voted Hitler and his fascist Nazi party into office?

The gleeful 'joy' of those who bought the property of Jews from the confiscating

government for next to nothing? The condescending comment of factory owners,

shop owners, practioners of the medical profession, academics employed

by universities who found it a big relief not to face bright and decent

'competitors' anymore - now that they had been excluded from competition,

robbed and driven into exile...? Or sent to the death camps, to the gas

chambers if they didn't grasp the looming danger in time. If they didn't

have the money, or didn't use it in order to flee. If they didn't

manage to obtain a U.S. visa or British visa or found another way to leave

Germany. Or Austria, for that matter.

I know that these old women and

men who reveal how much the past is alive in them were kids in 1940

or '44. By no means, killers. And yet, infected by propaganda. What about

the role of their fathers and grandfathers? Don't they remember?

Yes, sometimes people have a very selective memory. They were too young

to be willing helpers, it's true.(1) But

young enough to see Hitler as a kid, in

the papers. On photographs placed in their classroom. Or as he drove by

in a Mercedes, passing their town's main street, lined with waving people...

They evade certain questions,

those old bohunks and women who say "Hitler wasn't that bad at all."

Don't smear my father, my

grandfathers, they seem to think when they dodge your question. And

they have their mind filled with the diluted remnants of the old racist

poison...

Yes, don't think it's all over:

the generation of those who were 8, 10, or 13 when the last big World War

ended, is still, to a large degree, infected by what they heard, learned,

swallowed as kids. And what is worse, there are those among them who have

passed it on to their sons and daughters. And they in turn, to their kids.

Neo-fascism, racism in Europe is not something without roots. It's anchored

in history, in recent barbarity as well as the conservative restauration

that followed in '45. And let's not forget the much older, 2000 years old

anti-judaism of the Church.

2

Wherever you look today, racism,

xenophobia, right-wing reaction are in the air again in Europe. I

get scared when I note how it spreads anong segments of the young generation,

a generation often withhout hope, confronted with massive unemployment

(here and there, in Europe, it's affecting a quarter of those under 25).

I sense that xenophobia and a

disgust shown towards everything democratic, that the longing for strong

leaders, for 'law and order' is widespread and increasing in Europe.

A kind of 'law and order,'

of course, that begins to have the smell of that variety which Mussolini

and his black-shirted militants, cheered on by aristocrats, industrialists,

petty-bourgeois shopkeepers and school-teachers, had once preferred

to teach every democratic dissident artist or writer in Italy, by sending

him to prison or hitting him in the face.

'Law and order,' that might well

turn some day into a spectacle of the type which the fascists established

in Germany. And the Franquist 'falange' in Spain, their fascists

cousin in Portugal, the clerical fascist of the Dollfuss type in Austria

and Slovakia. Metaxas and his adherents in Greece. And the anti-semitic

right-wingers in Poland, Hungary, Romania...

'Law and order,' appended

today by an obsession with 'security,' is the concern in the minds

and on the tongues of those who willingly or unwillingly beef up neo-fascist

tendencies by repeating the talk of their elders that Hitler wiped out

the mass unemployment that affected Germany as a consequence of the crisis

that struck the country in 1928.

With one of the gravest crisis

at hand that this present economic system has ever experienced, in the

two-hundred or so years of its existence, the danger that authoritarian,

crypto-fascist trends will increase is at least as real as the chance that

more and more thoughtful people will demand economic democracy, participatory

rights, and respect for the environment as well as everybody's socio-economic

and socio-cultural needs.

For Alfred Hrdlicka as a citoyen,

it was self-understood that he take a stand against the danger of re-awakening

authoritarian trends. Against racism. Against the exclusion and marginalization

of minorities. Against the discrimination of women (not least of all the

sexually exploited, such as the whores he would draw and paint so often).

And it must have been clear to him that it was necessary to stand up for

everything that would limit the political influence and power of corporations,

of big business - the social forces that had alleviated and greeted the

rise to power of Hitler and his party. Dresdner Bank, Deutsche Bank, and

other financial institutions who had been so deeply involved. Mercedes-Benz

Corporation. German chemical industry. German steel industry. And their

Austrian look-alikes. Yes, Hrdlicka was 'red,' that much is clear; a 'red'

artist and an anti-fascist citizen. This is not the moment when it is possible

to probe the biographical sources of his committment. His working class

background. The ambiente of pre-war Red Vienna, with it tenement

buildings surrounding large courts, with its forms of blue-collar autonomy,

self-organization, its groping ways to invent self-help or mutual help.(2)

And

its bloody suppression, all of a sudden, that weighed so heavily on the

Left. No, it is enough, at the moment, to see that for him a separation

of his commitment as a citizen and his practice as an artist

was out of the question. Just as we could see in the case of Picasso and

others, life was a 'unity,' something not to be compartmentalized,

for him. Like Picasso, Hrdlicka was a politically conscious, very radical

individual

determined

not to wipe out this quality of his life in his work as an artist.

Especially before the cultural

turn of the late 1960s and the very early '70s, Hrdlicka, as an artist

determined to work 'against the current,' against the dominant spirit

of the era and the cultural policies that went along with it, must have

met with heavy resistance, in many quarters. Not only among the culturally-backward.

That is to say, in those petty-bourgeois

milieus where the prudish

and stiff attitudes as well as the retarded aesthetic 'tastes' of the so-called

'little man' triumphed. And thus, the ignorance and the limitations of

those whose character make-up was analyzed so well by Wilhelm Reich.

No, the bulk of the 'educated,' in charge of museums, galleries,

etc. and those responsible for the cultural interventions of the government

on its various levels (local, regional, national) must have seen him as

vulgar, as dangerously radical. As - in one word - anathema, an

enfant

terrible, and someone who must be shunned. Who must be boycotted, in

fact, to a very large extent. Because, to these people, he was simply

an 'obnoxious' sculptor who was obviously determined to violate taboos.

Giving a damn about everybody's wish to forget his shame and his involvement

in the Fascist nightmare. No, in the years of 'restaurative' politics (which

were felt with unspeakable force in that new and prospering state, the

Federal Republic of Germany, under chancellors like Adenauer and Kiesinger),

a sculptor like Hrdlicka did not stand a good chance to get a commission

for a sculpture that would be placed in the public sphere. A sculpture

that he would form in order to keep awake our consciousness of a barbaric

past. And in order to oppose every possibility of its return, in whatever

'new garb.'

But that changed, it seems, in

the mid- and late 1960s.

And epecially as a consequence

of '1968'! The changing 'social climate' lead in 1969 to the election

victory of a Social Democrat, Willy Brandt, in West Germany. And with the

changing political make-up of the Bonn government as well as the somewhat

livelier socio-psychological atmophere, in due time young academics began

to replace older, retiring men as town mayors, administrators of urban

cultural affairs, or museum directors.

Yes, in the wake of '1968' there

was change in the air. But it was met with resistance of course. On the

one hand, everybody could note a relaxation of the suffocating 'Cold War'

climate that had made possible the spirit of McCarthy in the U.S. and the

'prohibition of the CPG' (KPD-Verbot) in Germany. But soon, the new

wind of change subsided a bit, and there was a backlash. Directed, in the

first place, against the provocative students of the New Left.(3)

Still, the early 1970s were an

intriguing time. This was the time when a director like Peter Zadek challenged

the restaurative and provincial spirit rampant among the older audience.

He was good at it, as a director of the Schauspielhaus in Bochum.

The trade union federation (known in Germany as the DGB) organized the

progressive Ruhr Festival, the Ruhr-Festspiele, with its performances

of invited theater ensembles. In Oberhausen, Hilmar Hoffmann was in charge

of the International Festival of Short Films

(Oberhausener Kurzfilmtage).

In Munich, since the late

1960s, Fassbinder directed his provocative anti-teater.(4)

And soon he was also making his first films that offered scathing attacks

of the double-standards and the narrowmindedness so typical of the social-psychological

climate perpetuated after the war.(5) 'Katzelmacher,'

a film about an affair between a young Bavarian girl and a lonely Italian

immgrant worker, revealed the continuing presence of xenophobia and racist

stereotypes.

But you could also see a time

arriving when a mildly progressive, liberal generation of younger people

began to replace an older one - people who had often been implicated in

Nazism, who had superficially 'repented' and who had been white-washed

without significantly changing in many cases what was their basic,

very Conservative attitude towards life, morals, politic, and the arts.

The often intolerant stance of

the older generation that informed the prevailing practice of Kulturpolitik

[cultural politics] in the restaurative post-war years, had undoubtedly

been a brake, an obstacle to art in the public sphere, of the sort

Hrdlicka produced.

Yes, these old people and the

classe

politique which had nominated and backed them, had been responsible

for a cultural climate that had been stifling, provincial, and often banal.

There had been opposition to it all through the years, it is true. But

in the firt post-war decades, such opposition became a strong force in

terms of real influence perhaps only in the literary field. Here,

you could be ironic about the relics of the fascist era - as Boell, a member

of the progressive

Gruppe 47 [Group 47], was in some of his prose

texts.(6) You

could attack them in a sarcastic and revealing way, as Koeppen, the author

of

Pigeons on the Grass, and Death in Rome, did.(7)

You could call to attention of the public how the danger of a new fascism

was not over for good, as Alfred Andersch did when the Social Democrats

and Free Democrats, finally in power in the '70s, decreed the Berufsverbote

[ban to be employed in the public service, if you were considered a leftist,

a decree that even made a 'red' mailman jobless]. For the progressive writer

if he did not move (or was said to be) "too far to the left" (as Brecht

was), the avenues presented to him by the liberal publishing houses (like

Fischer and Suhrkamp) offered a certain possibility to swim 'against the

current' even before '68.

In the film 'industry' everything

progressive remained exceptional until the young film-makers of the New

German Cinema found ways of financing their works outside the 'industry.'

Becoming, in a way, self-reliant and inventive in their methods of finding

co-producers. Public television, to some, became an important source of

financing when, in the still young era of Social-Democratic chancellors,

major positions within the institution began to be staffed by members of

the younger, more open-minded, liberal generation. But conservative strong-holds

continued to exist, especially in the Federal Bureau that decided whether

to award subsidies to young and daring filmmakers who applied for them.

The decision to support a production was taken, not on the basis of assessing

the innovative character of the visual approach of a creative filmmaker,

but by judging the film-script he had to hand in. Such a decision was often

taken on the basis of narrow-minded, academic standards engrained in the

brains of mediocre cultural bureaucrats. As far as the problem of 'reaching

the public' was concerned, it was helpful that film critics like Wolfram

Schuette, Frieda Grafe, Enno Patalas, Peter W. Jansen, Karsten Witte and

a few others would write on the New Cinema. For instance in the left-liberal

Frankfurter

Rundschau and in the liberal Sueddeutsche Zeitung.

University

film clubs and Kunstfilmtheater

(a term meaning, literally, 'art-film

theaters') provided a much needed venue, as did the filmshows and film

festivals in cities run by liberal Social Democrats, especially in Mannheim,

Oberhausen, and in Hamburg.

But public sculptures, anti-fascist

art in the public sphere, paid for by the public, by city administrations

out of their budget for cultural affairs? It remained an unlikely proposal,

in West Germany, even in the 1970s.

3

Before the mid-1960s, Alfred

Hrdlicka's visibility as a creator of public sculptures was evolving slowly

under the circumstances of the time just sketched. Then, suddenly, in 1964,

he was one of two Austrian artist invited to the 32nd Biennale in Venice.

And three years later, in 1967, he was commissioned by the city council

of Vienna, which was dominated by Social-Democrats, to produce a bust of

Karl Renner, the deceased Austrian president (d. 1950), a Social- Democrat.

In spite of the strongly entrenched

Conservatives who were in power in the South-west German state of Baden-Wuerttemberg,

Hrdlicka was invited to teach as a professor at the Stuttgart Academy of

Fine Arts in 1971. Like Beuys in Duesseldort, he had to face a number of

colleagues who did not make life exactly easy for him or his students.

Though he was at least faintly

recognizable as a 'red', and an anti-fascist artist, a chance to create

a public sculpture in West Germany was offered to Hrdlicka in the late

1970s in Marl, a small town at the edge of the Ruhr District, today known

for its sculpture

mueum and for other, noteworthy cultural

activities that are not normally expected in a town of this size and relatively

minor economic importance.

The town was traditionally dominated

by the coal industry. And in 1938, the year of the pogrom against Jewish

citizens, the Nazi regime had established a Buna plant that produced synthetic

rubber (in the context of preparation for war) and subsequently employed

slave labor (so-called conscript workers or 'Zwangsarbeiter'). After World

War II, the mines had been modernized quickly and remained a major employer

until the coal industry was destroyed by the competition from corporations

importing cheap coal, often mined by underpaid labor under unsafe and technically

backward conditions abroad. But the chemical industry remains important

in Marl. Among the culturally progressive circles we must count the women

and men working at the 'People's University' (Volkshochschule), as well

as a number of trade unionists.

It was here that Hrdlicka realized

a bust of pastor Friedrich Bonhoeffer, a German conservative anti-fascist,

murdered by the Nazis in Ploetzensee, Berlin, on April 9, 1945, shortly

before the end of the war. |

Portrait of Dietrich Bonhoeffer (in Marl, Germany), 1977

Photo by Gerardus (2008) Re-published with permission.**

| The head has the simplicity

of a Buddhist sculpture; its expression is at once calm, strange, detached

and defiant. There is an energy that is discovered in or attributed by

Hrdlicka to this man. It is there thanks to the way he invented and formed

the head, the bust. And as we turn to it actively, thinking about it, sharpening

our senses, it becomes visible and thus 'known' to us. The roughly hewn

stone as well as the fragmentary character of the bust ascertain the modernity

of the work. A specific modernity - 'after Auschwitz': that is to say,

the modernity of an age which allows no reconciliation, no easy harmony,

no forms that do not express pain. |

Portrait of Dietrich Bonhoeffer (in Marl, Germany), 1977

Photo by Gerardus (2008) Re-published with permission.**

| The thoughtfulness of the face,

especially as seen from this angle, is striking. Is it to provoke thoughtfulness

in us?

Set in a nature-like, hardly

garden-like ambiente ( less 'tamed,' than a romantic 'English' gardenscape,

or 'French' geometrically strict Baroque garden), the fragmentary quality

of the stone stands out even more harshly. Like the ruins of cities, bombed

to pieces in the war. But there is also a nuance that lets me think it

is almost like the remnants of an ancient temple, set into the jungle and

prepared to be swallowed by it. Thus nature becomes a metaphor for that

which reconciles, a metaphor of that which "eats" and in fact "devours"

and thus "overcomes" the barbarous past of class societies that are

built on blood and sweat and tears. The blood spilled by henchmen, tools

of barbaric rulers. The sweat of the common people who let exploitation

and tyranny happen. The tears of all those, guilty or not, who suffer.

It was in 1981 that Alfred Hrdlicka

could create his Frederick Engels Monument (Friedrich Engels Monument)

in

the birthplace of Engels, Wuppertal, an industrial city in the immediate

neighborhood of the Ruhr District, governed by a Social Democratic mayor.

It was here that the city administration had also created a place of remembrance

and research, in the house where Engels had been born. This fitted their

purpose to keep documents of Marx and Engels under indirect Social Democratic

control, as in the case of the Karl Marx house in Trier where the social-democratic

Friedrich Ebert Foundation is in charge. Obviously, guarding (and 'occupying')

a certain heritage of the party was a purpose; it went hand in hand with

minor economic considerations. It is always considered a small boost to

tourism that a town can boast to be the native place of one of its sons

who has become famous internationally. Not only academic researchers from

within Germany and from abroad are welcome visitors, but the average 'curious

tourist,' as well. Hrdlicka, for whom the authors of the Communist

Manifesto must have had quite a different significance than that attributable,

in all likelihood, to politicians, 'culture managers' and other bureaucrats

in Wuppertal, apparently was ready to find his own answer to the quest

for a sculpture in memory of Engels.

The Friedrich Engels Monument in Wuppertal; Germany

[Segment of a ] photo by Atamari (2009)***

The reference to Engels is not

immediately, certainly not 'automatically' recognized. Two human figures

erupt or protrude from the stone. Castor and Pollux? A metaphoric representation

of Engels and Marx? Yes, maybe for some the work alludes also to the two

friends and co-workers sharing a joint project although they are certainly

not 'recognizable' in any 'naturalistic' sense... But then, it alludes

to MAN, perhap man and woman, thrown into the 'human condition' of PREHISTORY

where MAN is still subject to exploitation, to needless forms of suffering,

to what is irrational and alienating. Does it then refer to the project,

the preoccupation of Engels - to his perception of MAN as the beaten, suffering

creature in need of emancipation? Twisted, tangled limbs, the bared ribs,

a chest seen as if partly opened, the entire distorted, fragmentary presence

of the human body - does not all of it testify to the pain inscribed in

human existence, as long as class-societies are changing their character

without overcoming the division into ruling and ruled, exploiting and exploited

classes? And yet, there is also togetherness. The beauty that shines through,

in even the dark moments in life. And the joy of being alive. Puzzled,

wondering, the figure to the right stares at something. The ground? Its

own body? Nothing - because the INNER eye SEES and turns INWARD? And the

figure to the left? Throwing back its head in pain? Or staring, enraptured,

at the sun? Into the blue sky?

O yes, I asked myself what the

hands are holding: is the man holding a baby? And the woman, a scroll?

About four years later, Hrdlicka

was awarded the opportunity to realize the Counter Memorial (Gegendenkmal)

in

Hamburg, begun by him in 1985 and completed in 1986. |

Counter-Memorial ("Gegendenkmal"), in downtown Hamburg, Germany

Photo by Staro. Republished with permission.*

| The fragmentary character of

the work, as well as the violence incribed into the aesthetic language

found by the sculptor, are perplexing, in fact deeply disturbing. This

is the antithesis of any 'usual' language suggested by other, conventional

sculptors who have so often been asked to create monuments in memory of

those who died in the last war. Or in the other big, terrible World War.

The monument is located downtown,

set into a small park. Before the jarring outline and coarse surface of

the main body of the work which appears like a tableau of a world tormented

and about to be torn asunder by chaotic, violent forces, a dark human figure

is faintly visible, leaning against it as if in agony, the agony of dying.

In front of it, separated by the grass of the lawn, the fragmentary, headless

body of a woman, her left breast bared, her left leg distorted though not

disfigured, erupts from the stone. Springing from it, merging with it.

Burned into or onto ruins. Where we would expect the throat to sit on the

rump, something seems to flow from this body - the lungs? Perhaps it is

the visualized pain which flees it and yet is glued to it like a dead fish,

a flounder or flatfish.

Something like a steel rod, a

beam, a long, geometric corpus (made of, who knows, iron, bronze,

steel?), connecting the female torso and the main body of the monument,

hits the human figure exactly where we feel the presence of its absent,

torn-off, smashed, annihilated head.

Other rods or beams stick out

from the monument, protruding nearly vertically into the air. Or they are

visible as relief-like, almost horizontal beams in front of it. Do we think

of smashed, shattered houses, bombed habitats, crumbling and about to fall

down?

Further to the left, also separate

from the main body of the work, a strange, almost surrealist stonen form

rests on a high pedestal. Its form, and the dynamics inscribed into it,

let me think of flames flaring up. But it evokes also a giant wing of a

bird, a cruel bird of prey, not a real one, of course, but the mythical

eagle that tore the flesh away from the heart of Prometheus.

That which is figurative and

thus recognizable, though deformed (a bit like Picasso 'deformed' his human

figures), and that which remains a riddle, form a single but dispersed

work: accentuating the question posed, a question which demands from

us to take a stand.

Every passer-by will tell his

story, of course, as he turns to the counter-monument. I can only tell

mine.

Only two years after Hrdlicka

had completed his Counter Monument in Hamburg, his own city, Vienna,

the Austrian capital where Hrdlicka lived and worked, asked him to

create the Memorial against War and Fascism (

Mahnmal

gegen Krieg und Faschismus ) on the Albertina Square (realized

in 1988-1991). |

'Gate of Violence' (Tor der Gewalt), part of the

Monument against War and Fascism, Vienna

photo by Hans Weingartz***

| Here, the location of the work

is not a small park but an urban square amidst pre-19th and pre-18th century

houses that either survived the war unharmed or that were reconstructed.

The shape and color of the two

elements of the monument that are known as the 'Gate to Violence' (shown

above) bear witness to the fact that Hrdlicka in fact respects the character

of the architectural environment. He respects it in so far as the

finely grained and not at all non-harmonic texture of the high pedestals

almost takes up and repeats the color of the cobble stones. The sloping

surface of the pedestals takes up the angles of the roofs of the surrounding

houses. The whiteness of the sculptured figures takes up the white color

of the walls of the buildings. And the almost cozy, well-nigh romantic

atmophere of the built environment seems to be as if echoed

by playfully baroque shapes. But the playful movement seemingly inscribed

into the forms, the lines, the volumes of the sculpture are the outcome

of terrible and terribly painful distortions. The human body is deformed,

ripped apart, it even stands on its head. As in the case of the female

figure in the Hamburgian Counter Monument, the human figure grows

out of the stone. Breasts and arms appear from it; quite on

the top of the sculpture, I see bones which must belong to a leg that no

longer exists in its entirety. Snakelike, other elements of the human body

are emerging from the white stone, some almost winding themselves around

part of it. What seems, at first sight, an ensemble of playfully entangled

limbs, turns out to be the outcome of the most negative, life-annihilating

destruction. |

Another view of Hrdlicka's Monument against War and Fascism

photo by Gryffindor (2006) ***

| As in Hamburg, but now even

more radically perhaps, Hrdlicka turned the monument into an ensemble of

separated parts that you can enter, that - as a pedestrian - you

can cross. And probably are supposed to cross, to walk through, that is.

In other words, you become, for seconds or minutes, not an onlooker glancing

at it from outside it, but a part of it - drawn into it. Involved. Asked

to see and touch, to sense and relate corporeally, to confront, to reflect,

to feel, think, and act. |

Another view of Hrdlicka and his work:

"The starkly disturbing 'Memorial Against

War and Fascism' has been occasionally defaced since it was unveiled

in 1991."

"Known to have been deeply influenced by his

studies of the mentally ill during the late 1960s, Hrdlicka turned to a

figurative expressive style meant to provoke his audience to confront the

world's anguish, pain and misery.

For him, art was agitprop and he understood

his life as an artist as a mission to educate the public to oppose war

and violence."

"His oft-cited dictum, 'all art comes from

flesh' is reflected in his later works. For Hrdlicka, art that avoided

the human condition was nothing more than decoration and not to be taken

seriously."

(From: George Jahn (AP), "Austrian news

agency: Artist Hrdlicka dead", in: http://www.google.com/hostednews/ap/article/

ALeqM5ioaTtRzqgXIGkmQtYEzon9FsCGiQD9CDEEG00) |

|

|

External link :

See 'Junge Welt' article on A. Hrdlicka

(by Oskar Lafontaine)

(backup

copy) |

| Right below the 'Gate to Violence'

(of the Viennese Monument against War and Fascism), another monument

done by Hrdlicka attracts the marvelling attention of the person who opens

his eyes, actively and watchfully looking at the world around him.

It is the figure of an old, bearded

man, cowering, crawling on the ground - one hand, the right one,

slightly raised in the air. As if asking you to be understood. To be taken

out of - and freed by you from - his humiliatory situation. To be saved

from his anxiety, his torment, and his tormenters.

The main accent of the sculpture

is on the thrust forward, the imploring gesture, the desperate face that

turns to you, serious, earnest, facing the enormous. Confronting it, as

if in prophetic clarity, it sees, perceives, the scandalous absence of

humanity that it is subjected to.

Seen from the front, the body,

the back, behind, legs, feet seem to shrink perspectively - giving an even

greater impulse to the thrust forward, the accent put on arms, hands, and

above all, the face - the earnest trait of which heralds already the turn

of history, the nemesis, the defeat that will destroy the destroyers of

human dignity, human values, and millions of human lives.

Statue of a Kneeling Jew

Photo by KF. Re-published with permission.*

The photograph reproduced was

accompanied by a short commentary of the photographer, K.F. He, presumably

a citizen of Vienna, tells us that in 1938, shortly after the annexation

of Austria, Jewish Viennese men were forced by the Nazis to scrub the pavement

with brushes. He explains that this was perpertrated in order to humiliate

and terrorize the Jewish citizens of Vienna.

He also mentions that this work,

unveiled in 1991, was repeatedly defaced by rightists and that it

is located at the base of the Monument against War and Fascism (at

the Albertina Square).

Actually, the sculptured body

of the old Jew lying flat of the ground is faintly visible as a dark

grey patch, immediately to the left of the pair of white sculptures

seen on the photo of the entire ensemble of the Monument against

War and Fascism.

In 2008, Hrdlicka realized another

monument called Orpheus I in the ambiente or context

of the Viennese Monument against War and Fascism. It is an androgynous

figure, showing an enraptured face, curling hair, arms raised in a sensuous

way, revealing a great Yes to life, the body, its existence. The breasts

are bared, the upper part of body turns, voluptuously; a big male

sexual organ hangs down between the legs. The figure bends forward even

if only slightly, as if expressing a longing. Turning towards something

or somebody, ready to give herself (or himself).

Of course, in Classical Greek

mythology Orpheus symbolizes life, he symbolizes that which overcomes

death. It is the figure of the mythical singer and poet who crosses the

river between life and death, who visits Hades, the realm of the dead,

and returns to the living as a living person. But there is another, disconcerting

quality about Orpheus. He loses his love, Eurydike, to death. He is unable

to bring her back to life. The pain remains. The pain in art, in artists,

poets, singers - in fact, in every feeling, thinking human being. The dead

are dead. The victims of the fascisms of the world, from Germany to Spain,

Italy, Greece, Indonesia, Chile and Argentine. The victims of terrors and

gulags, the victims of wars - and how many were going on, since 1945, and

are still going on... Yes, and those many millions who died unnoticed,

in the midst of peace, as a result of avoidable hunger and misery and exhaustion,

of despair and isolation. They are gone forever. They'll live never again.

Orpheus I (bronze, 2008)

© Manfred Werner Republished with permission.*

What is the janus-headed, androgynous

character of this figure called Orpheus if not the contradiction

inscribed into our world and our time? The tension, between opposites:

innocence and experience, the life-asserting and the life-negating tendencies,

the joy and the pain of living in a world torn at and shaken and thrust

into abysmal chaos by the irrational conditions men still perpetuate.

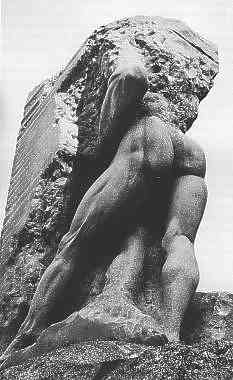

Orpheus - Hades*** Orpheus - Hades***

The tall, sculptured body bending

forward, of a life-asserting Orpheus I returning from Hades, facing

the world in pain, sadness, memory of loss, but also with great vitality,

is accompanied by its corresponding part (not counterpart!),

Orpheus

in Hades. A figure of painfully searching, active, energetic flesh,

diving into, thrusting itself and in part disappearing

into the ruins

of the world, a stone fragment from which an arm, its elbow, a behind,

two legs protrude. The back of the man who is known as Orpheus merges with

the rough surface of the stone. The head has vanished in the stone. The

figure, actively, energetically trying to grope, to hold on to someone

or something (it must be Eurydike), seems intent to draw that which it

holds on to, from the darkness of imprisoning dead matter. Is it

a leg that appears between his legs spread apart? Or the trunk of a tree

- the tree of life contradicting the stony world of ruins, into the foliage

of which the head and chest of Orpheus has disappeared?

After having already created,

in 1977, the bust of pastor Bonhoeffer in Marl, Hrdlicka formed another

memorial that paid tribute to a German victim of fascism. It is the Menorial

for Eugen Bolz, sited in Stuttgart and accomplished in 1993.

Apparently a bronze, it shows a skinny, naked individual facing - terrified,

anticipating, clear-sighted yet hopeless - the torturers. Situated in front

of the naked wall, its rough structure, the figure of the man we see protruding

relief-like from the bronze wall is standing under a hook. The kind of

hook pigs would hang from in a slaughterhouse. He awaits, without hope

for salvation, for survival, the bestiality of the end that is foreseen

for him by those who make themselves his inhuman masters - the beasts more

beastly than beasts. The hook of course alludes to the hooks in Ploetzensee

where a number of prisoners of the Nazi regime awaited execution, among

them the Conservative conspirators who had hoped to blow up Hitler in his

bunker in East Prussia. When the Red Army conquered Berlin in spring, 1945,

the living opponents of Hitler and the world discovered that the prisoners

that were executed in Ploetzensee were left dangling like pigs, after undergoing

whatever torture the henchmen could think of.

Memorial for Eugen Bolz, at the Koenigsbau in Stuttgart (1993)

Photy by Enslin, 2006 Re-published with permission.*

We who face the Memorial for

Eugen Bolz are dumbfounded. And perhaps not only by the intensity of

the anticipation of a barbaric, terrible, lonely death suffered by the

individual thrown into the hands of the Nazi killers. The strangely cut-off

part

of a hand, growing from the bronze wall - what does it point to? What

does it signify? The hand, is it the hand of a man who swore to defend

the republic, and who died, trying to keep his promise?

Hrdlicka has not only turned

his vision as a sculptor back to the last world war, to the cruelty and

inhumanity of wars generally, and to the Fascist past. In Berlin,

where he also installed an ensemble of tableaus in Ploetzensee (not

shown here) that is dedicated to the foes of fascism who were killed in

its 'execution shed' (or 'Hinrichtungsschuppen'), he created a memorial

that he called Death of the Demonstrator. Its site, in front of

the opera house known as the Deutsche Oper, makes amply clear that

it refers in an immediate sense to the death of Benno Ohnesorg, a student

shot during a demonstration against the Shah of Iran when this head of

a murderous, torturing regime paid a visit to the 'governing mayor' of

West Berlin in June, 1967. Standing out relieflike from the nearly rectangular,

tall but slim block of bronze, we see the dynamics of action. Helmets of

policemen, arms, legs, a club, helpless hands of an invisible person in

the background, the face of an onlooker, twisted limbs, perhaps of

a person 'subdued' by the cops. The face of the onlooker is concerned.

The cops look away, their faces not really visible, more of a void, an

emptiness under the helmet. Are they dodging responsibility? Merely

obeying orders? Functioning very well? We have seen all that before, in

another era. But are men ready to "function" without listening to their

conscience, again and again?

Death of the Demonstrator (Der Tod des Demonstranten), relief.

Photo by Lorem ipsum. This file is licensed under Creative Commons

Benno Ohnesorg was shot, incidentally,

not by the West Berlin police who clubbed peaceful, democratic demonstrators,

quite in line with the atmosphere created by the press and leading politicians.

He was shot by an inane, ordinary little man, the kind Wilhelm Reich described

in his small book, Listen, Little Man! He had to die because the

heated atmosphere created by the media (that turned ordinary 'little men'

against the protesting students!) had poisoned the minds of a large number

of people in this city in '67.

Hrdlicka took pains not

to dedicate the memorial exclusively to Benno Ohnesorg. He dedicated it

to all demonstrators who have died because they took to the streets in

order to demand freedom and civil and other rights.

And thus, the memorial is for

those killed yesterday in Athens, the day before yesterday in Genoa, years

ago in Managua or Santiago de Chile,and who knows, tomorrow in a place

where they still think "it can't happen here."

Hrdlicka, although he died, will

remain alive in his sculptures of which quite a few have been placed in

the public sphere, just as he will live on in his lithographies, etchings,

drawings and paintings.

Notes:

(1) It is important to realize today that they

were so many "willing helpers" of the Nazi-engineered millionfold genozide.

So many, in so many roles. Policemen who knocked at the door, telling people

"Make yourelf ready for a long trip." SA-people and cops who herded them

to the station. Railway men who transported them to Auschwitz, to

Buchenwald, Dachau... Then, guards... Torturers...

(2) See: Helmut Weihsmann, Das rote Wien:

sozialdemokratische Architektur und Kommunalpolitik 1919-1934. Wien

(Promedia) 1985. Cf. also: Walter Oehlinger, Das rote Wien 1918 - 1934.

Wien

(Museen der Stadt Wien) 1993 (exhibition catalogue)

(3) The Old Left had been legally outlawed

in West Germany under American influence, just as it had been outlawed

in South Korea and Taiwan where military, fascist-like dictatorships relied

on emergency law, a state of siege and concentration camps like the one

the Greek junta later established in Leros and Jaros, with apparent though

tacit U.S. and NATO approval...

In contrast to West Germany, the situation

was different in post-WWII Austria, thanks to the achieved unification

of its formerly Soviet and Western occupied zones, and as a consequence

of its neutral status. We must remember that the Adenauer government, under

American pressure but perhaps also of its own accord, rejected the proposal

of the Stalin-led regime to make possible immediate German unification,

under the condition that the united Germany would be neutral, like Austria.

The proposal though made quite seriouly was discredited in the media as

a farce.

(4) It was in 1967 that Fassbinder joined

the Munich action-theater which became the anti-teater

in the following year.

(5) It is necessary to mention here Liebe

ist kaelter als Tod [Love is Colder Than Death] (1969), Katzelmacher

(1969),

and

Warum

laeuft Herr R. Amok? (1970).

(6) Boell's story entitled Hauptstaedtisches

Journal (1956) was the text that Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle

Huillet used for the dialogues and narrator's voice in the film Machorka-Muff

(1963).

A.H. Weiler commented in 1969 in his

review of the film in the New York Times that, in this (actually, his earliest)

film "Mr. Straub, employing the cold, somewhat expressionistic but always

loquacious approach of his other films, comes closest to underlining the

almost subliminal irony of his themes. He briefly outlines, through the

performance of Colonel Machorka-Muff, a former Nazi who is reinstated in

the Adenauer regime, the unchanging thinking of the Nazi and/or the military

mind." (A.H. Weiler, "Screen: German Newcomer's 3 Films:Straub's Entire

Output Shown at New Yorker Circuitous Approaches to Reality a Pattern",

in: The New York Times, Feb. 24, 1969

(7) Wolfgang Koeppen, Tauben im Gras

(1951) was published in Englisch a Pigeons on the Grass, New York

/ London (Holmes & Meier) 1991; Tod in Rom (1954) was published

a Death in Rome, London (Hamilton) 1992.

IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING THE PHOTOGRAPHS USED:

Permission to re-use these digitalized images was granted under the

following condition (indicated by one asterisk or two or three asterisks

following the caption of each photo):

Case 1:

*Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document

under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any

later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant

Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the

license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License".

Case 2:

** I, the copyright holder of this work, hereby release it into the

public domain.

This applies worldwide. In case this is not legally possible:

I grant anyone the right to use this work for any purpose, without

any conditions,

unless such conditions are required by law.

Case 3:

*** (Version a:) Diese Datei wurde unter den Bedingungen der „Creative

Commons Namensnennung-Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen Deutschland“-Lizenz

(abgekürzt „cc-by-sa“) in der Version 3.0 veröffentlicht. (i.e.

creative commons).

(Or version b:) Diese Datei ist unter der Creative Commons-Lizenz Namensnennung-Weitergabe

unter gleichen Bedingungen 3.0 Unported lizenziert.(i.e. creative commons).

(Or version c:) Ich, der Nutzungsrechtsinhaber dieses Werkes, veröffentliche

es hiermit unter den folgenden Lizenzen:

Diese Datei wurde unter der GNU-Lizenz für freie Dokumentation

veröffentlicht.

Es ist erlaubt, die Datei unter den Bedingungen der GNU-Lizenz für

freie Dokumentation, Version 1.2 oder einer späteren Version, veröffentlicht

von der Free Software Foundation, zu kopieren, zu verbreiten und/oder zu

modifizieren. Es gibt keine unveränderlichen Abschnitte, keinen vorderen

Umschlagtext und keinen hinteren Umschlagtext. (i.e. creativre commons)

* |

go back to Art in Society no. 10, CONTENTS

ART IN SOCIETY

* |