| Jacob van den Broek

The Challenge and Difficulty of Being A Realist Artist During the period of Kuomintang rule in China, critical artists began to develop a new taste for woodcuts. The technique was old and well-established in China. But Chinese woodcuts, in contrast to (traditional) Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy, was not cherished much, either at home or abroad. If one thought of East Asian woodcuts, Japanese works of art came to mind. Then, in the period of social tension and increasing civil war, progressive artists discovered the work of Kaethe Kollwitz. It was the beginning of a flood of laconic, straightforward, sharp and piercing Chinese art works, relying on the traditional technique but contemporary in their modern, stark realism and apparent social commitment. It is this achievement, born out of a concrete social

situation and filled with the combative sarcasm and bitterness

of years of intense class struggle, that elevated Chinese woodcut making

of the 1930s and 40s to the level of original, autonomous East Asian art

that transcended its European realist predecessor.

Gerhard Bettermann, a German artist born in 1910 in Leipzig,

has captured in his own way something that is also inherent in the Chinese

woodcuts just mentioned.

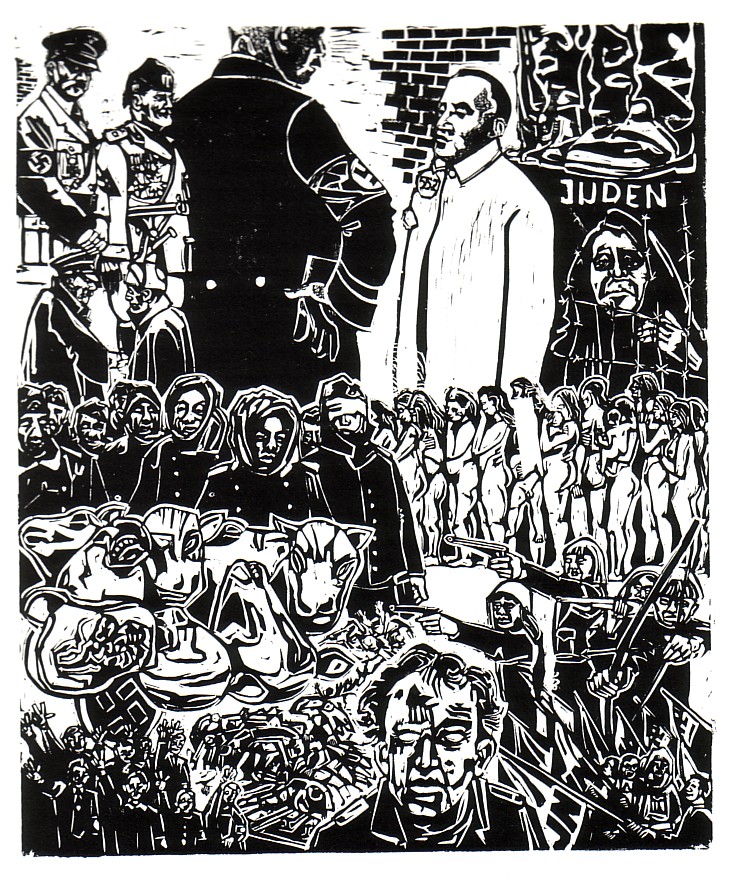

When we turn to Vicious Circle, a linocut (67,2 x 56 cm) done in 1979, we cannot fail to notice the presence of the past. The composition relies on a montage of basically two kinds of elements: the element of the anonymous masses, and the element of the singled out types. The first are inserted as strong horizontal columns, dynamically

arranged in echelon formation, and thus seemingly in (albeit slow) motion.

Naked European humans, lined up, some carrying babes, are haltingly moving,

perhaps pushed, forward, from right to left, towards the death chambers.

Set against these small, basically horizontal mass scenes juxtaposed in black and white, there are vertical elements. A man, with bruised forehead, reminiscent perhaps of the young Mao, marches in front of the peasants and their oxen, quite a distance ahead of them, singled out, put into the foreground, as a peasant leader. The view we get of this figure has been cut off slightly below the collar of his dark jacket. He seems to stand below the podium of world history from which we, the audience, look at him. Is he addressing us or confronting us? Perhaps it depends on the viewer. Too other towering figures – one black, one white, filling

much of the upper half of the work’s space – are more prominent, however.

Vicious circle is a dynamic composition that includes stasis and movement, the past and the present, the pre-war warnings of Kollwitz, the unimaginable perversities of millionfold murder committed by Germany's Nazis, and the revolt of liberation movements in the Third World during the ‘30s, the ‘40s, the ‘60s and ‘70s. As such, we may read it as a work of art that dramatically expresses a tension that unites today and yesteryear, the memory of defeat and genocide in Fascist Germany, the awareness of conservative restauration and of silence, in the face of world-wide injustice, in liberated Europe. And finally, the calls for help, from the Third World, the renewed attempts of suppressed mankind, to gain freedom. In contrast to the interpretation offered above which

sees in the work a juxtaposition of those who went passively to the slaughterhouse

and others who, politically more conscious, offered (and offer) resistance,

another reading is also possible. It would interpret the “uniformed” peasants

joining liberation movements as a “flock of sheep” following new seducers,

and as a threat to peace and individualism, while seeing in a renewed world-wide

class struggle the beginnings of another period of “chaos” as well as an

opportunity for the spectre of fascism to raise its head again. Is this

the “vicious circle” the title alludes to?

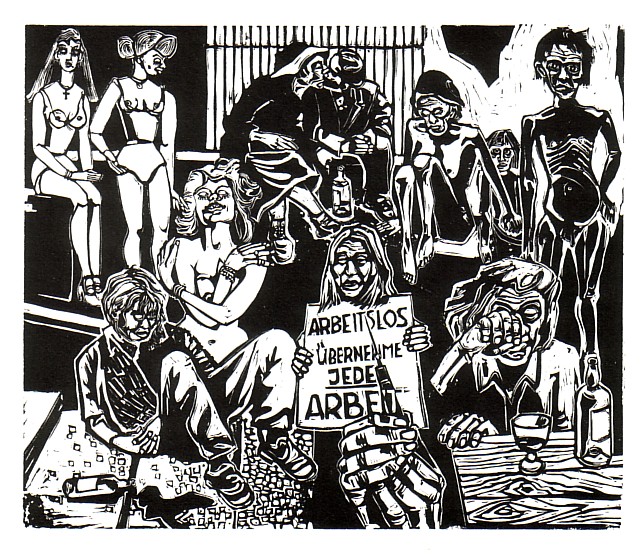

Another work by Bettermann, again a linotype done in 1979, is called Economic miracle. It alludes to the term coined by the Conservative German Chancellor Ludwig Erhard that glorified the post-war boom of the '60s in Germany. The “September strikes” as well as the economic crisis of 1967 and 1969 had foreshadowed the long downturn of the Kondratiev cycle beginning in 1973, with its ever increasing mass unemployment in Western Europe. Bettermann mingles an image of consumerism stemming from the super-chic post-war boom period, symbolized by flashy, scarcely dressed girls (apparently ready to sell “love”) with the harrowing views of recurrent or simply more visible destitution and poverty. Again, types rather than individuals represent the social ills diagnosed. There is the drunkard, hopeless and resigned to his fate. Then we see the unemployed person, holding up a piece of cardboard that is telling us something like “Will work / for food”. There is the young kid, left in the street, down and out, sitting next to his half-naked girl-friend; both may well be on drugs. At the margins, we see a figure from far-away Africa: a reminder of the world-wide scourge of unnecessary famine and stark hunger, typified by a human being, “thin to the bones,” with wide open, expressive eyes and sorrowful mouth.

The work is a straightforward J’accuse, an attack leveled at a world ready to ignore millions of excluded human beings. A rich world, in the North, to be sure. But rich also in the guarded compounds of its accomplices in the so-called Third World. Betterman who travelled widely in Europe and Egypt between

1927 and 1932 (years of “vagabondage,” they have been called), was a victim

of Nazi administrative actions taken against “degenerate art” in 1937.

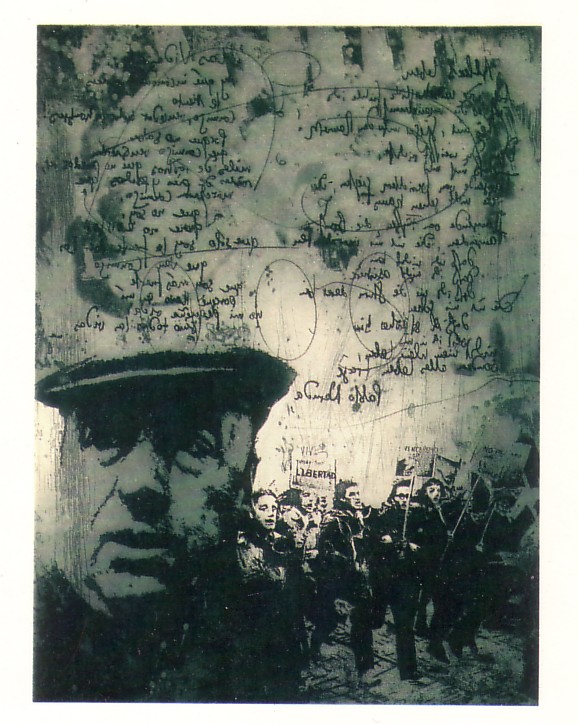

* * * Klaus Boettger, born in 1942 in Dresden, uses elements of montage (and collage, as well?), in works that recall moments of social struggle but also defeat. Las Vidas, zu Pablo Neruda combines a portrait of the poet, a negative photographic image of a hand-written page with his poetry, and young people racing ahead in the street, during a demonstration in Chile. Banners carry the word LIBERTAD.

His montage technique seems more contemporary, more part of the 1970s than the approach chosen in the case of Bettermann’s works which are still rooted in the pre-war years. If we look at the poem as a found object, if we reflect on the photographic source and the method of combination of the images used as elements in the work, if we marvel at the magic effect of the light that appears like a new dawn arising (or perhaps more like a threatening flash of light in the dark?), we cannot help sensing the aesthetic influence of surrealism. The same is true of the dreamlike appearance of Neruda’s

face in the foreground, and of the way the words of his poetry appear as

if written into the sky by an imaginary pen.

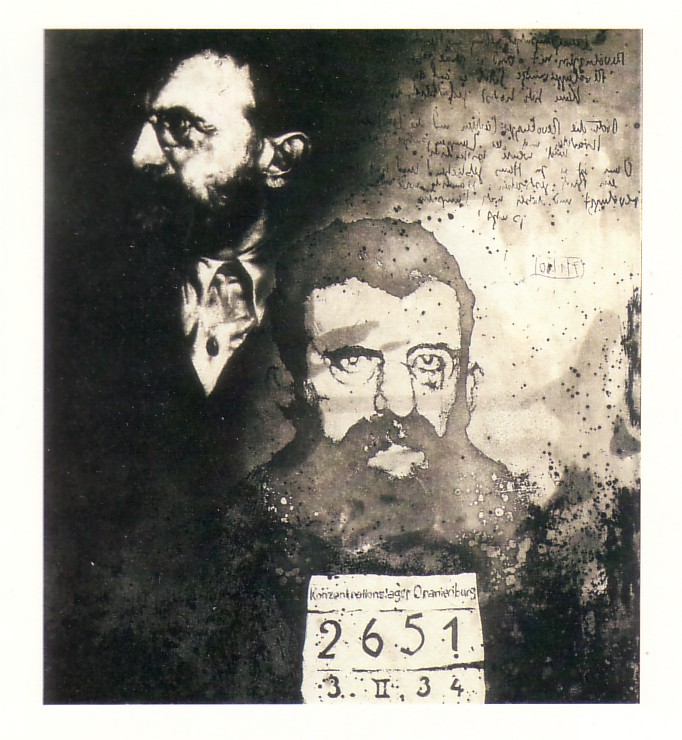

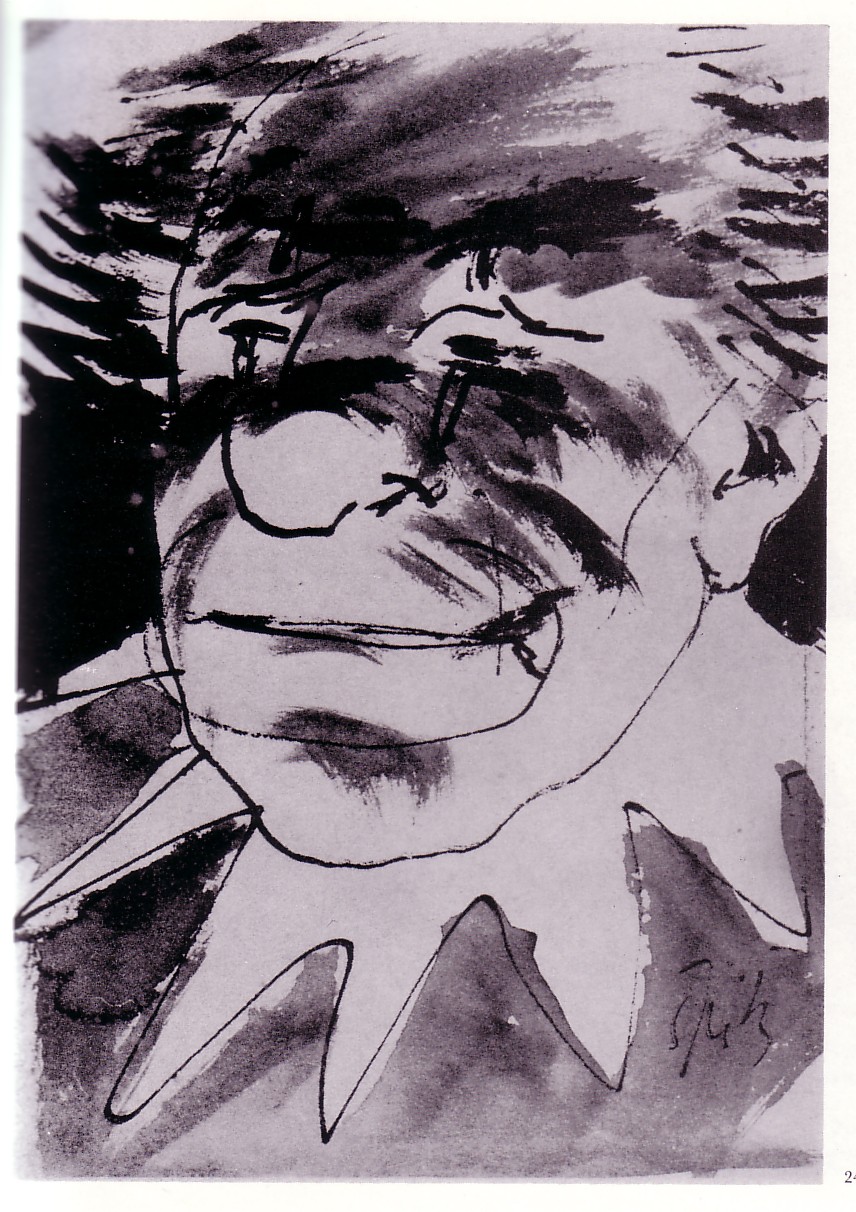

In a similar way, a work like Zu Erich Muehsam, dedicated to a German anarchist poet murdered by the Nazis, combines elements that bear witness to Muehsam's existence as a poet and to his prison existence and death in dreamlike fashion. A page of his writings appears in the background above him, as if written onto a prison wall partly lightened up by a source of light somewhere beyond the art work, and in fact, in the eyes and mind of the observer. The poet’s wide-eyed face looks at us with terse and determined, half-open mouth.

It appears to us, not as a naturalistically represented

face, but rather as an image projected onto the prison wall, into which

also the words of the poem have seeped like black ink.

* * * Ernest Špitz, born in Czechoslovakia in 1927, is another

realist artist influenced strongly by the experience of Fascism. Echos

of the Nazi German occupation, liberation from Fascism by the Red Army

in 1945, and of the subsequent years of Stalinism can be deciphered in

his śuvre.

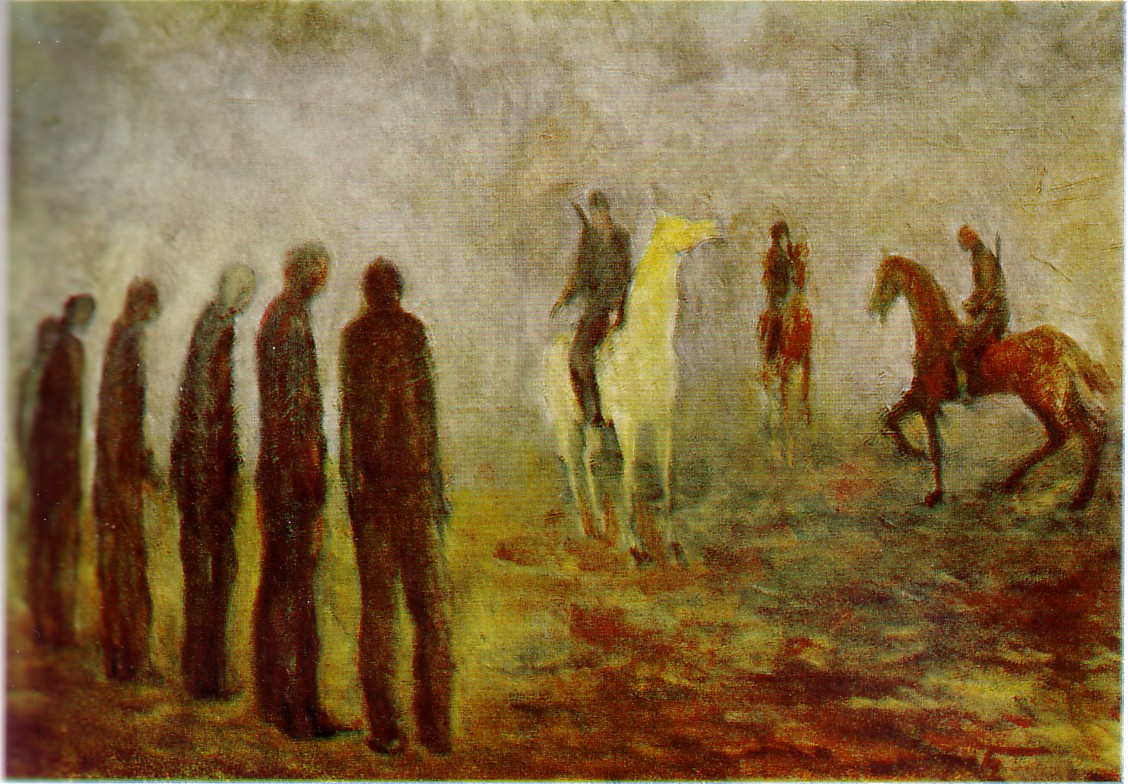

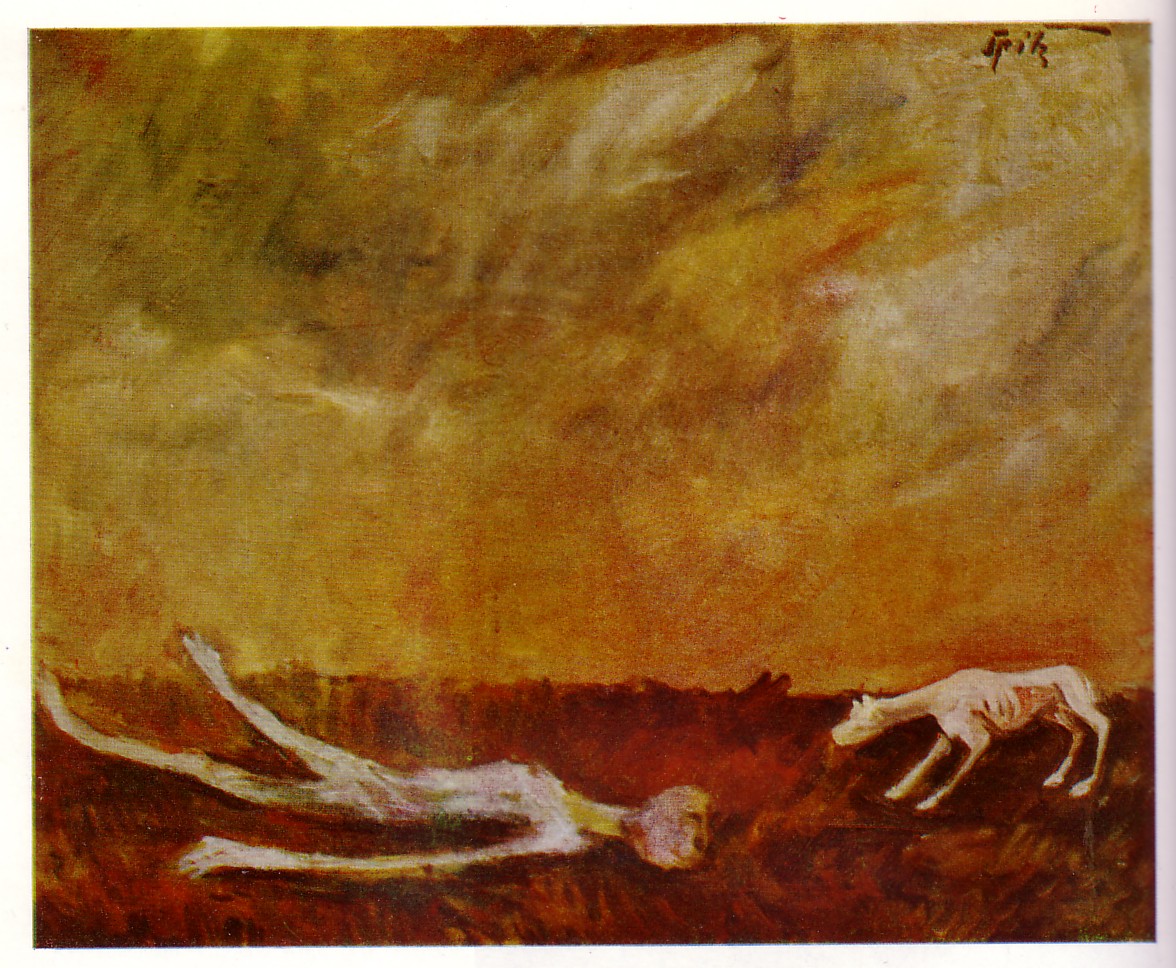

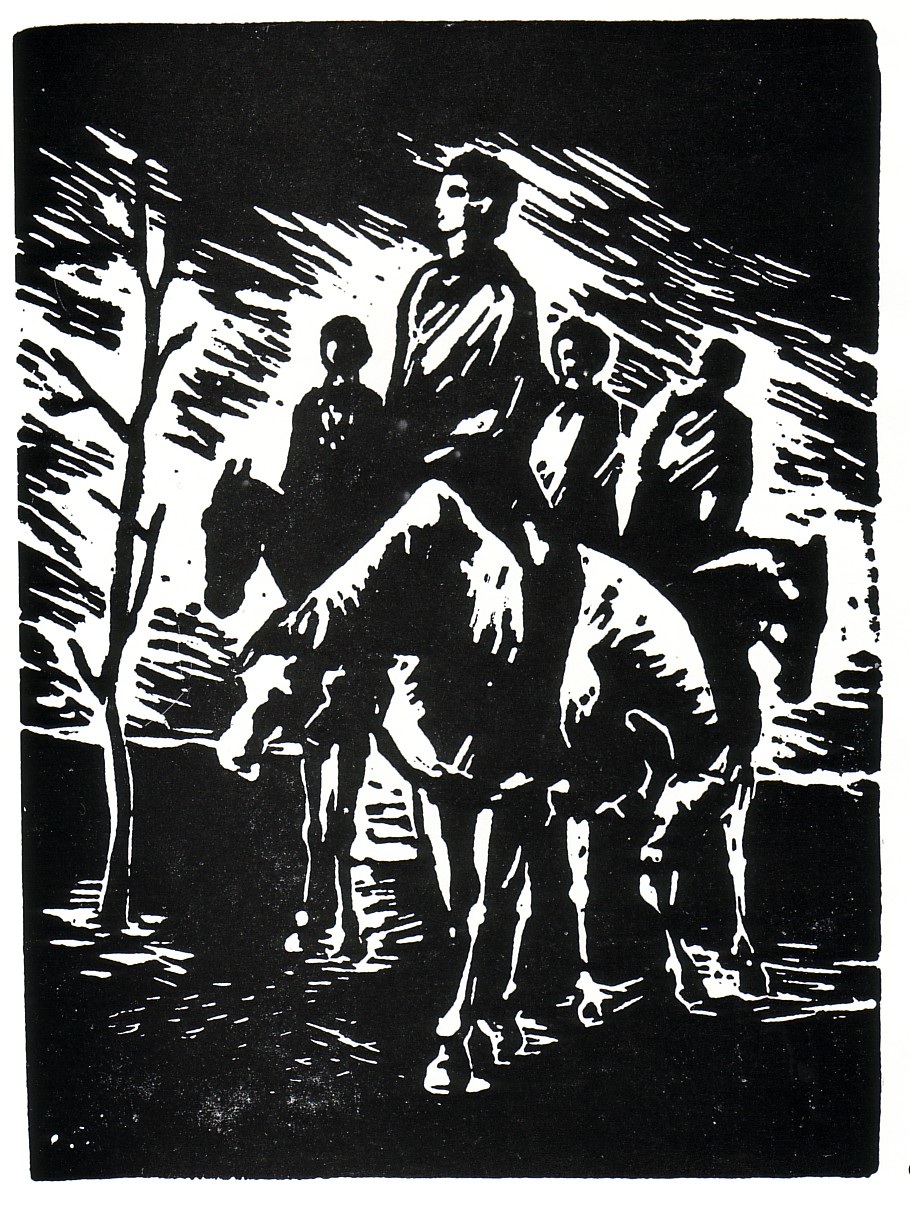

The desolation captured in Neistota (1957) is janusheaded, and thus irritating. There is the row of dark figures, maybe prisoners liberated from a concentration camp still dressed in their striped prison wardrobe. Lined up as they are, they seem to look full of anticipation, perhaps, but also full of doubt, at a uniformed figure on a pale white horse, a man who is brandishing a gun, and carrying a rifle on his shoulder. Two other soldiers on horseback are visible a little behind, and to the right of, the first one. The horses are restless, whinnying. Their restlessness as well as the twilight sky mirror the openness of the situation that announces a new day or a new hell. Incertainty above all. But also hope of a new beginning, as the light erupts faintly and the fog lifts? Another possible reading would let us see the moment before an execution, by members of the Sonderpolizei or Wehrmacht soldiers. The sky in Zbytky (1948/49) takes up more than two thirds of the canvas. The colors leave no impression of transparency; on the contrary, they are thick and gloomy. They are reminding us of a sandstorm. Or of a sea of flames that rise up in the distance.

Embracing parts of the sky, their reddish and ochre hues

leave scarce space for a few remnants of grey, small glimpses of greyish

light that are appearing nightmarishly among traces of darker olive greens

and blackened blues.

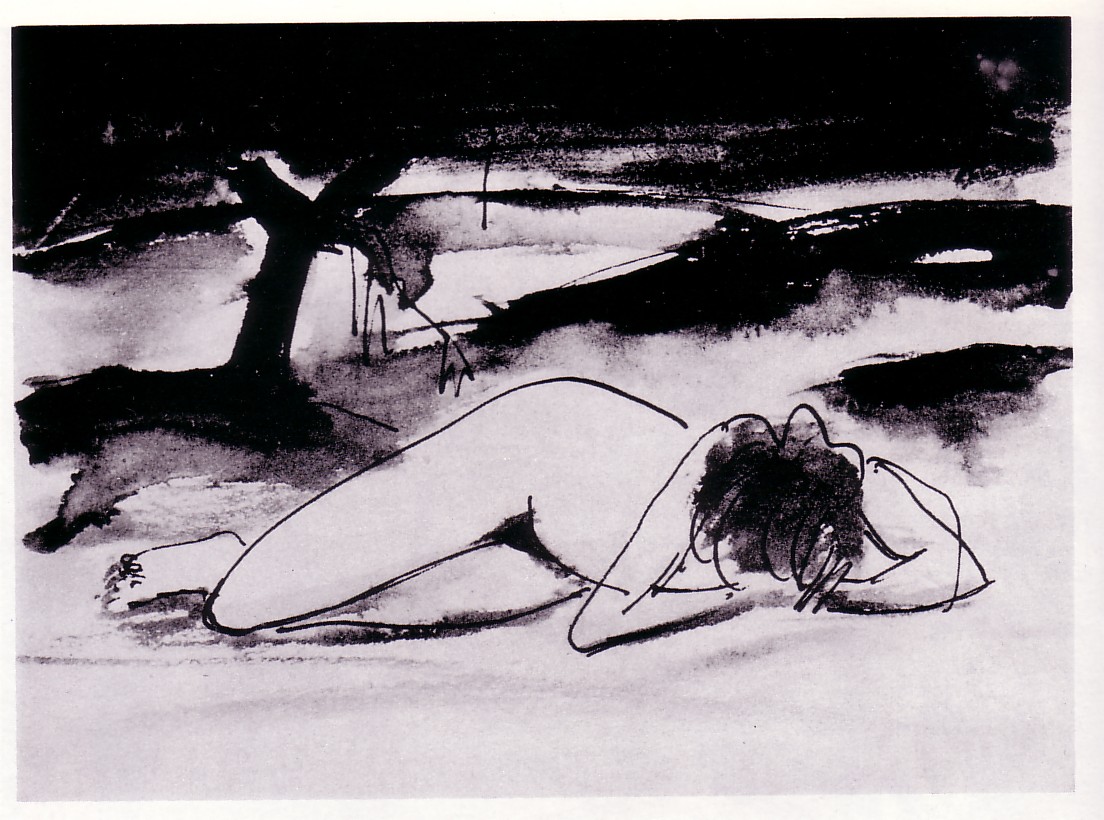

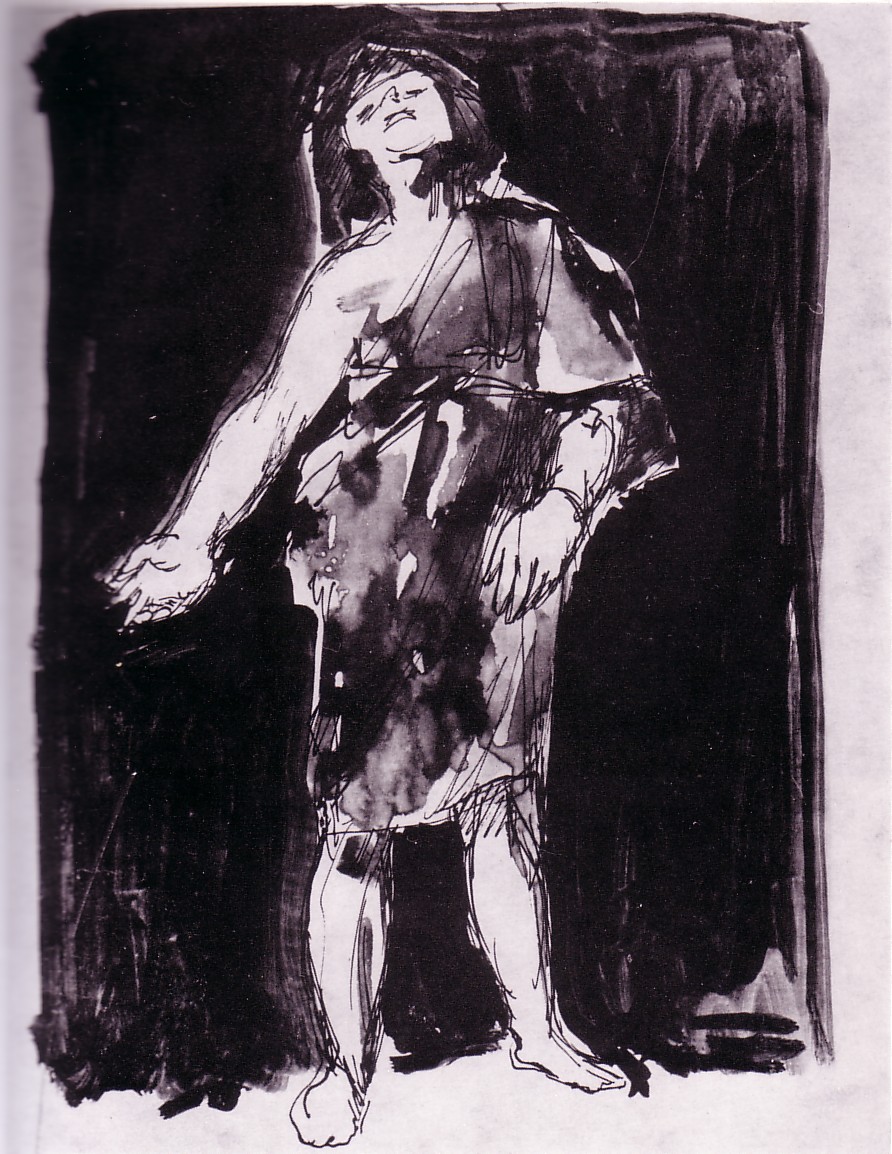

The same sujet has been transposed into a wintry landscape, in Opustená (1946/47), a work showing a naked woman in the foreground, her beautiful body standing out starkly in front of the raw icon of what may be a shattered cross by the wayside.

As in some works by Franz Kline, the effect of black strokes

of color set against whiteness is almost abstract, yet suggestive of a

landscape, its most elementary qualities. While the indication of hair,

the fine outline of the legs, back, belly, and arms introduce a figurative

element again...

In 1948, Špitz did light – and at first sight, optimistic – colored drawings of village life, with partisans and Red Army soldiers figuring as welcome liberators (Partizáni v dedine (1948); Vítanie sovietskeho vojaka (1948)).

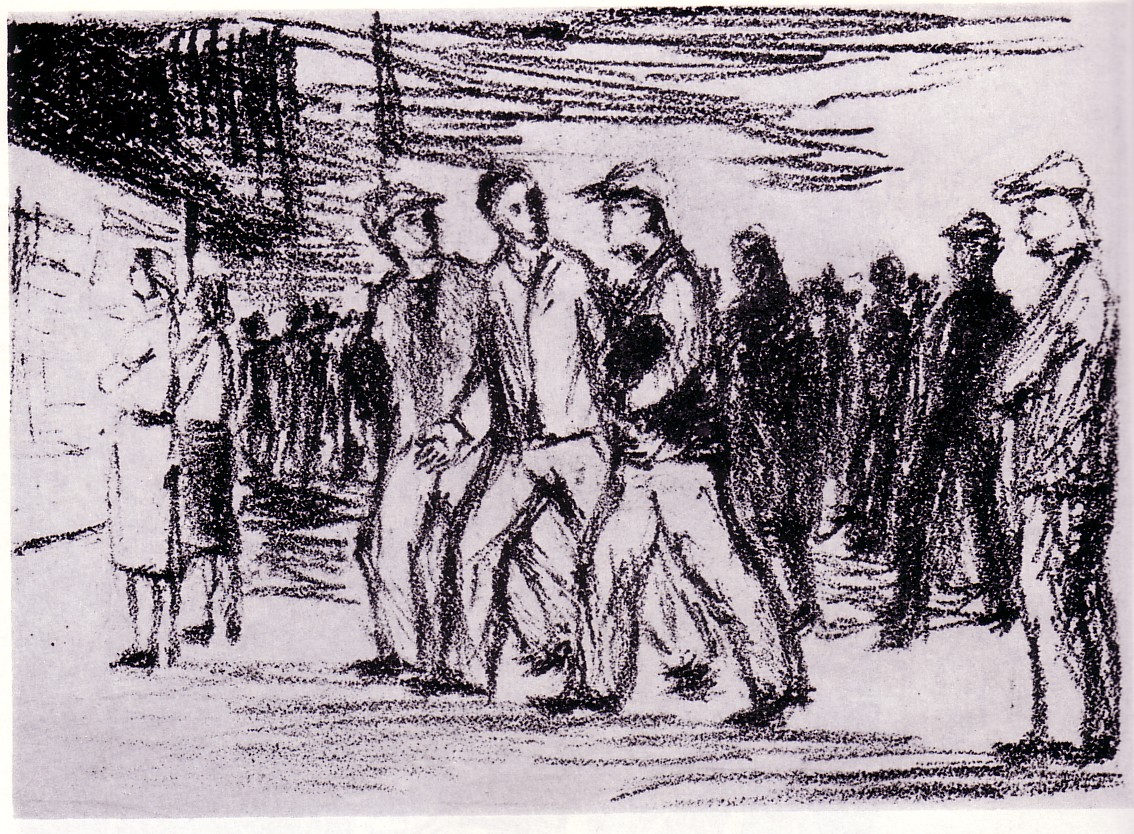

It seems that Stalinist bureaucrats in charge of overseeing the art scene demanded something different, more combative, in the end. And so, a charcoal drawing, Do práce (1951),

shows workers drawn to what must have been an official announcement glued

to a factory wall.

The middle group of three workers is shown to be full

of determination and energy.

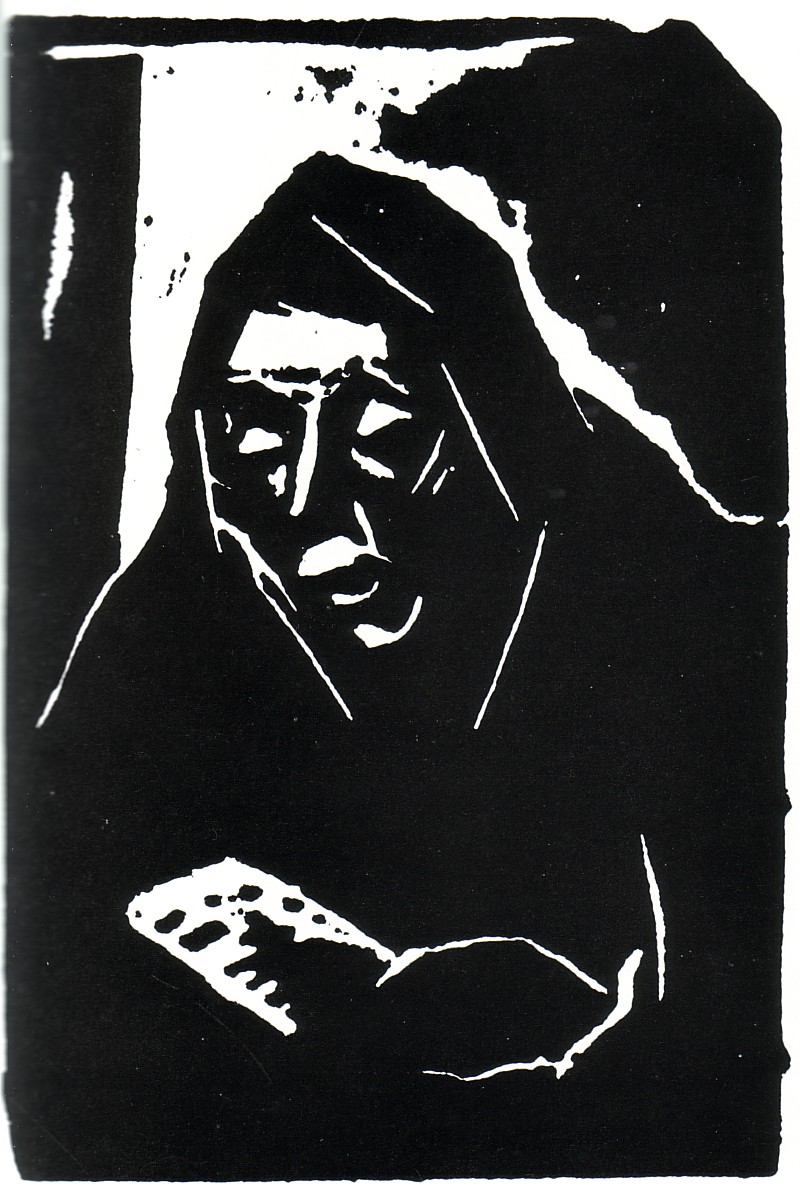

In 1953-1954, Špitz did a number of prints that hardly show the optimistic side of life. The old one in Starena (1953/54) is very present, resting in herself (or himself?), showing the traces of what may have been, more often than not, a hard life. But there is no bitterness or accusation in this face, just an acknowledgement of facts.

Jazdci, another print from 1953/54, shows a group of young people on horseback, in the windy day of approaching springtime. Its mood is not neutral; there is a slight expectation felt, an awareness of the forces of life arising, amid a world of harshness and difficulties. In the white areas interrupted by black traces reminiscent of hatching that this print features, the ‘light,’ the ‘day,’ and the ‘wind’ are present. And because the black areas outweigh the white ones, the presence and intensity of WHITE are even more strongly felt. The drawing V parku, a sketch done in 1951, shows Špitz as an artist who is gifted, as well, when drawing. A scene of nature, in this case.

The sketch is nervous. The spring wind brushes a person

seated below a tree and what may be another, small person passing by.

An individual, that’s how the clown, too, comes

across, as we start to see him truly, underneath his make-up or mask (Clown,

1956).

And the same may be said of the gypsy girl (a real one,

or an actress), portrayed in 1957 in Po vystúpení.

During the second half of the nineteen fifties, Ernest Špitz did a number of peaceful impressionist paintings, often devoid of human beings, of contradictions, as if he wanted to avoid difficulties and tried to escape from a weird reality. A modest Acadia, a very tangible space of quietude, a retreat in the Slovak countryside is present in Tri suché stromy (1957), and similarly in Dom v záhrade, done in the same year.

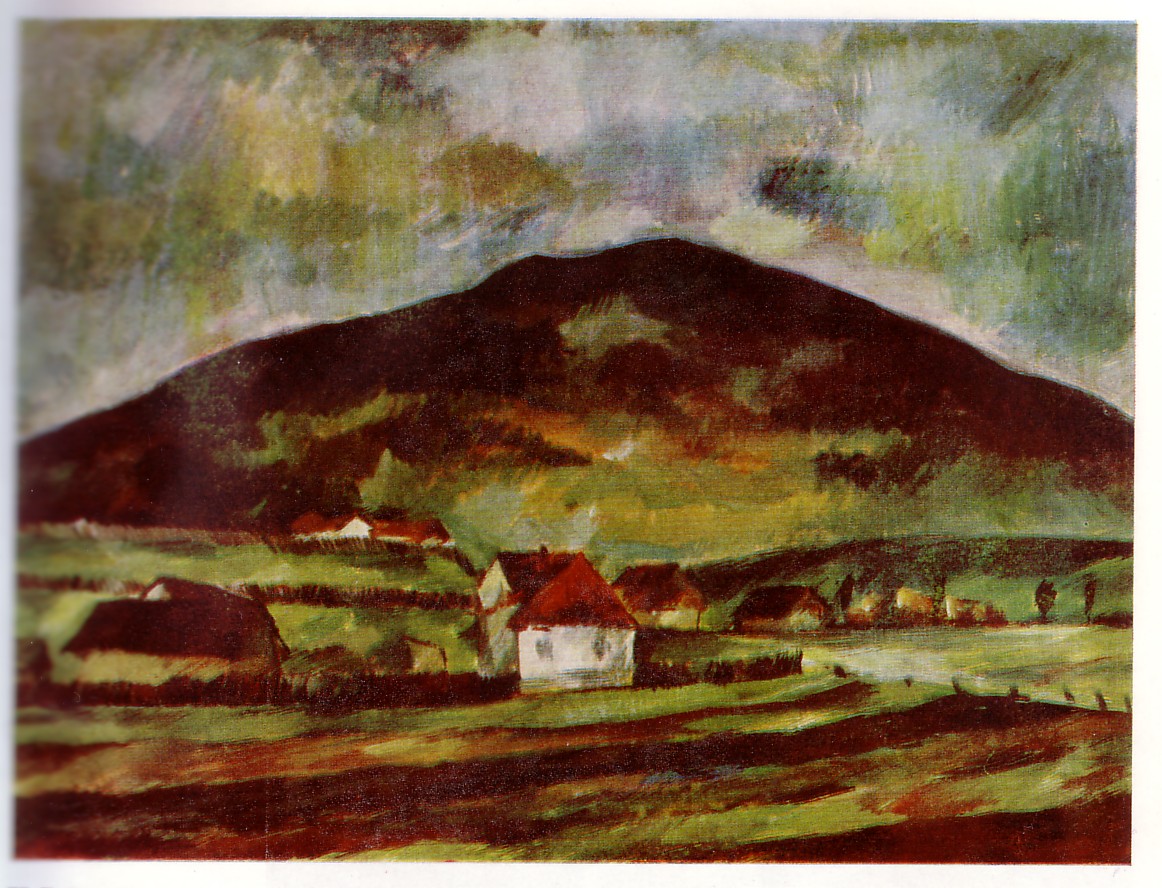

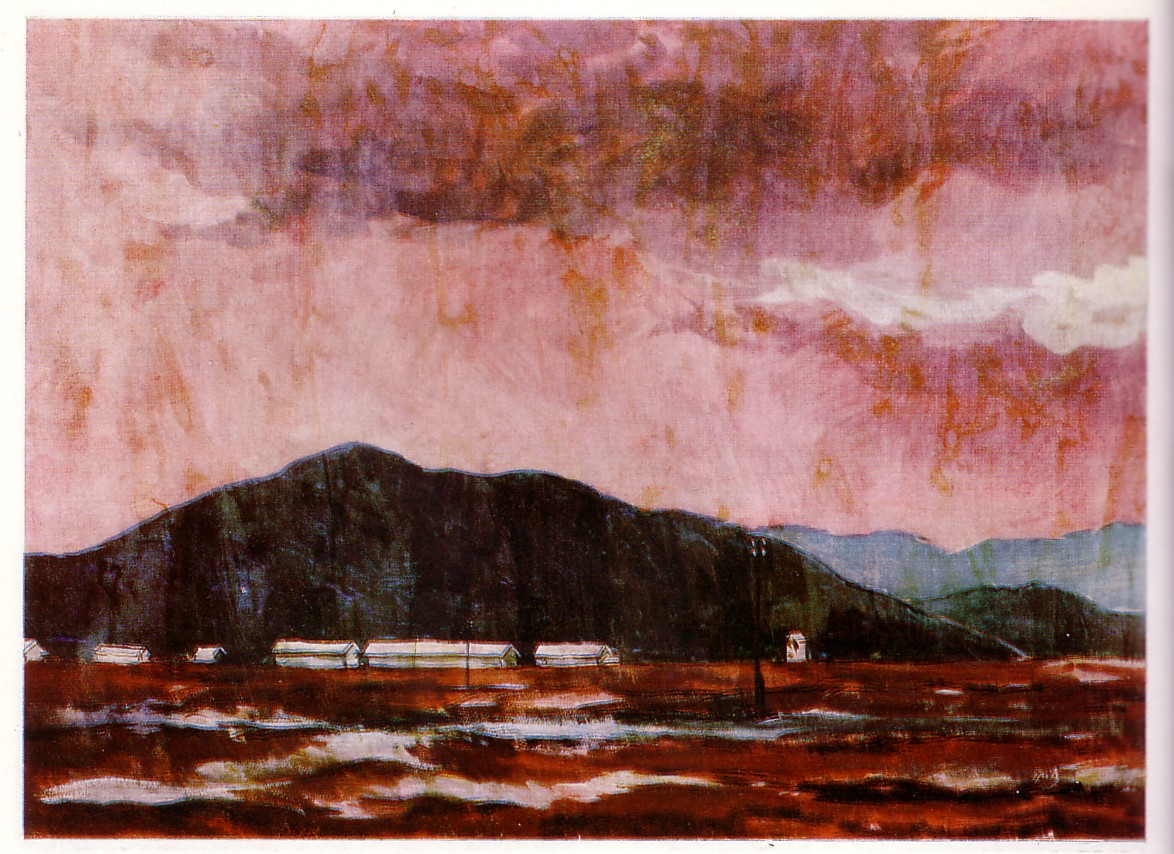

But other paintings reflect an inner restlessness, convulsion, suffering, as the dark, rainy landscape painting Krajina (1957) and the industrial landscape Krajina v Liptove (1957). In this painting, the sky is a sulphoric red, reduplicated by a dark crimson earth. The mountain hovers threateningly, like a black dragon’s back, above the row of white, elongated buildings that may belong to a mining ventury or a factory.

Perhaps this mood was appropriate in view of the janus-headed

effects of the Stalinist expansion of the industrial base in Czechoslovakia.

A work like Mesto nad riekou IV – Nocturno portrays a nocturnal

view of what may be a Kombinat – a towering industrial ensemble,

complete with mine shaft and lighted, many-storeyed buildings, that appears

like a moloch; the surrounding area in the foreground looking like tons

of discarded shards. The wounded earth, one might say. While exhausts,

from a dozen valves and pipes, rise vertically into the sky, hiding the

sun behind their dirty veil.

* * * Ernest Špitz, like the other artists, Gerhart Bettermann and Klaus Böttger, who are presented briefly in this short article, is an interesting and noteworthy realist artist, close to the socio-cultural reality that surrounded him. The difference between the works of each of these artists cannot escape our eyes. I feel that this is not a purely individual difference. It can be related to the fact that their formative periods belong to different eras and / or different places, even different socio-cultures. This finding contradicts of course the assumption voiced by a German ZDF television reporter, reporting from the Venice Biennale in 1995 who stated, bluntly, the mainstream view on art and its rootedness when saying, “By now, everybody knows that the time has passed long ago when national specifics were apparent in the arts.” (Inzwischen weiss doch jedermann, dass es nationale Eigenheiten in der Kunst schon seit langem nicht mehr gibt. [ZDF Second German Television, June 16th, 1995] ) It is strange that mainstream opinion which makes an

instrumental use of nationalism whenever it can (think of the British

– Argentine Falkland / Malvinos war and jingoism in the British media,

or the last two Gulf Wars and U.S. chauvinism), determinedly denies cultural

specificities and pleads for globalized homogenization. I do not

want to join into the Stalinist diatribes of the '30s against an ‘international

style,’ or mistake Stalin’s instrumentalization of nationalism and ‘national

art’ (in fact, it was merely misused and cleansed folklore) for

a progressive contribution to the debate. It was Gramsci who, in nuce,

developed a much better theory of folklore. Nationalism, except where it

served to shield tossed around and subjugated populations from

cultural imperialism, is a questionable ideology indeed. But to underrate

the creative relationship of art (thus, of artists and the recipients)

to a specific social reality is as questionable. Perhaps the works

of the artists discussed here give us a sense of socio-cultural difference,

despite the progressive stance they have in common.

[A prior version of this text has been slightly revised by the editor in Sept. 2014.] |

*