Antonio Cuadrado-Fernadez

Creative-(ex)tensions: Indigenous eco-poetics as counter-hegemonic

discourse

Research Paper presented by Dr. Antonio Cuadrado-Fernandez at the 1st

International Symposium “Re-founding Democracy”. Barcelona, 21 - 23

May 2015.

Short abstract: In this paper I aim to use

a phenomenological approach to the Indigenous poetry of Hadaa Sendoo (Mongolia),

Humberto Ak’abal (Guatemala), and Walissu Youkan (Taiwan) in order to

propose an alternative notion of identity based on the writers’ shared

sense of interconnectedness to the environment. In this way, the embodied

experiences emerging from the poems can be articulated in a common empowering

counter-hegemonic discourse against the ontological and epistemological

foundations of global capitalism. Similarly, the paper proposes that the

poetry projected in this articulatory, empowering discourse from three

bioculturally diverse regions shows paths towards alternative ways of living

in the Anthropocene.

Thank you for giving me the opportunity to present this

paper in this symposium.

I’d like to start with a quote by Francophone anti-colonial

writer from Martinique, Aime Cesaire, a quote that connects beautifully

with the spirit of my talk:

“I have a different idea of a universal. It is of a

universal rich with all that is particular, rich with all the particulars

there are, the deepening of each particular, the coexistence of them all”.

Whatever happened to the anti-colonial, humanist spirit

emanating from the thoughts of Cesaire and also Sedar Senghor, Frantz Fanon

or Jean Paul Sartre, the truth is the postmodern theories that were supposed

to channel this spirit into concrete action have failed to persevere in

the enormous task of creating emancipatory horizons for an increasingly

violent neo-colonial world. Part of the problem might be attributed to

the tepidity of postcolonial theory when addressing postcolonial struggles

in terms of cultural difference and identity politics, which has advantages

and disadvantages.

Focusing on identity and cultural difference has been

helpful in giving visibility to the numerous spatial trajectories (nations)

and cultures emerging after the decolonisation process in mid-twentieth

century. Within the umbrella of cultural difference and identity, issues

of gender, ethnicity or class can be highlighted and receive an individualised

and highly localised treatment. In other words, criticism of postcolonial

literary texts focuses mainly on the writer’s biographic micro geographies.

However, there are reasons to believe that the mere celebration

of cultural difference known also as postmodernity might not be sufficient

to address the pressing realities of corporate globalisation, a point that

is amply referred to by Fredric Jameson when he rightly claims that “this

whole global, yet American, postmodern culture is the internal and superstructural

expression of a whole new wave of American military and economic domination

throughout the world: in this sense, as throughout class history, the underside

of culture is blood, torture, death, and terror.”

More specifically, the reason why the empowering message

of anti-colonial writers has been diluted is the incapacity of postcolonial

and other postmodern theories to transcend the subject-object dualism on

which modernity was solidly grounded.

Postcolonial theory “speaks” the language of poststructuralism

which deconstructs space conceived mainly in terms of binaries: subject

boundary object, self boundary world, mind boundary body. It is in this

scenario where the idea of culture has ended up fetishized as a commodity

in the service of the capitalist-neoliberal ideology from which cultures

were supposed to be liberated.

“[P]erhaps in the case of space, the scientific legitimacy

of atomistic imagination has been of critical importance in providing a

background to a cosmology of an essentially regionalised space, to claims

for the belongingness of people with its place, for the

necessity of boundaries against incursions from an essentially

foreign outside […]”

It is difficult to conceive of an articulating postcolonial

discourse if space is deployed in discrete, isolated entities, if the postcolonial

writer is represented as mere cultural distinctiveness, exclusively in

terms of its biographic relation to place, however important cultural distinctiveness

may be. It is clear the alternative to political stagnation is political

articulation. In this sense, the work of Argentinian sociologist Ernesto

Laclau opens a theoretical and practical path in that direction, when he

claims that:

“There is no way that a particular group living in

a wider community can live a monadic existence – on the contrary,

part of the definition of its own identity is the construction of a complex

and elaborated system of relations with other groups”. In other words,

the mere celebration of cultural difference is clearly not enough in a

world where the former colonial structures of domination have been expanded

and refined under the ideological umbrella of neoliberal capitalism, deeply

affecting the chances of survival of Indigenous (and non-indigenous) communities.

Indigenous poetry and the methodology

The previous analysis of the glory and pitfalls of multiculturalism

can also be applied to contemporary Indigenous poetry. Traditionally, Indigenous

poetry has been the vehicle through which Indigenous communities have expressed

their worldviews, protest and resistance against colonial and neo-colonial

forms of exploitation.

However, this poetry has mainly been analysed and approached

from the standpoint of its cultural distinctiveness, on the writer’s

biographic micro geographies, on what makes him/her distinctive from “other”

writers, as if poetry were the crystallisation of individual thought. But

this approach fails to acknowledge the potential cross-cultural connections

that pervade the poems and it fails to notice that the worldviews it projects

are sustained on place-based epistemologies, rooted in oral tradition,

which is an embodied and emplaced form of knowledge. In this sense, despite

the obvious cultural differences, the poetry of Hadaa Sendoo (Mongolia),

Humberto Ak’abal (Guatemala), and Walis Nokan (Taiwan) share a profound

cognitive and sensory engagement with the physical environment.

And despite the poets’ different modes of land occupancy

(Akabal ascribes himself to Mayan mostly agricultural form of life; Sendoo

to the nomadic lifesteyle of the Mongolian steppes and Walis Nokan to the

hunter-gatherer and fishing Indigenous tribes of Taiwan), their imagery

projects an image of land as a network of meaningful places, entities,

and experiences of transmission rather than a stage or a backdrop where

events simply occur. The environmental logics underpinning the imagery

in their poems can be read as multisensory, relational, open ended, dynamic

creative processes of engagement with the environment, challenging contemporary

mechanistic, commodifying and capitalist modes of production. What is needed

is a method of reading that articulates the reader to the writers’ embodied

perceptions, from what neurophenomenologists call empathy. From this perspective,

empathy and cooperation are built into the hardware of survival as we are

biologically social animals that learn by imitating, sharing, observing

and ‘placing ourselves in other personas.’

In this interaction of the reader with the writers’

Indigenous worldviews, the analysis aims to articulate bodily experience

to the writers’ environmental logics. Now, how is this type of phenomenological

reading possible? Inspired by neuroscience and phenomenology, new research

in cognitive linguistics and poetics reading, Cognitive poetics views the

language of literary texts as rooted in the body’s perceptual system.

In general terms, cognitive poetics explains what happens

in the mind when literary texts are read, focussing on conceptual and sensory

information emanating from the text as the reader progresses. In other

words, cognitive theories help us understand what happens in the mind as

readers cross the space of the text. Cognitive poetician Reuven Tsur defines

reading as a spatial orientation because the part of the brain that gets

activated when we read is the same that operates when we attempt to find

orientation in space. Particularly, Tsur argues that there are two types

of reading — rapid and delayed categorisation. With the latter, reading

is a linear, concept packing activity; we cross the text as we travel by

bus or train from place to place, point to point — the important is

the destination, the meaning of words. On the contrary, a delayed-categorisation

type of reading is slower and allows the mind to extract the rich sensory

information that emanates from the text. Once this space is opened

for ‘navigation’ the conceptual and sensory information is analysed

by readers as they enter and enact such information in the different geographical,

temporal and social mental spaces created by the writer.

Psychogeography of Indigenous poetry

A journey through the poetry of Humberto Akabal is a journey

through the cognitive and sensory dimension of his Qitz language, which

is the language he uses to write the poetry that he later translates into

Spanish. Akabal is one of the most internationally recognised Indigenous

poets, he has won numerous awards, and, above all, he fiercely defends

the Indigenous worldviews of his Mayan community, which pervade his poetry.

As we will observe in the other two Indigenous poets, Akabal’s relationship

with nature is reciprocal; it is a relationship between two living beings,

which in turn is an inherent part of the writer’s identity and of Indigenous

collective identity as well, because to Mayans, human’s ultimate humanity

resides precisely in their capacity for metamorphosis. This can be seen

in one of his beautiful poems, “Color of Water”, where he metamorphoses

with a tree, in an image of splendid simplicity: I search for my shadow

/ And I find it in the water. / I have branches / I have leaves/ I am a

tree… / And I look at the sky / As trees look at it:/ The color of water.

The poet doesn’t need sophisticated imagery to find

who he really is; he just needs to look at his reflection in the water

to find himself fused with elements of nature. If we adopt a delayed categorisation

type of reading we can reproduce in our mind the image of a man and a tree

as one; an image where the poet has inherited part of the attributes of

the tree, and the tree part of the attributes of the poet. From the perspective

of cognition, this is called conceptual blending, which is the capacity

developed by humans during the Palaeolithic to innovate, which gave them

the ability to invent new concepts and to assemble new and dynamic mental

patterns. The results of this change were awesome: human beings developed

art, science, religion, culture, refined tool use, and language. In this

respects, the proponents of conceptual blending suggest that human imagination

is the product of bodily interaction with the environment.

Particularly, conceptual blending is based on the idea

that the mind operates by eliciting associations that allow humans to operate

in and interact successfully with the world, in that sense, it is like

a metaphor, that is, the mind works like a metaphor. In the case of the

poem, the metamorphosis might be explained as the result of a complex perceptual

process of interaction with the environment in which the tree and the human

body are cognitively mapped initially to produce a new emergent entity.

Likewise, with a delayed categorisation type of reading,

it is possible for readers to elaborate the sensory information emanating

from this image, as if the writer were as robust and resilient as the bark,

as rooted in the land as the tree, as adaptable to change as the tree…Conversely,

the tree can be imagined as the flexibility and sensitivity of a human

body….

Hadaa Sendoo is a Mongolian poet and translator whose

poetry has been translated to more than 30 languages and he has been widely

published everywhere. The poetry of Hadaa Sendoo takes the reader to the

plains of Mongolia, to the smoke of the yurt, to wandering camels, to nights

filled with stars traversed by nomadic families. This is an ancient life-style

threatened by the prospect of the mining boom of Mongolia’s earthly fortunes.

Hendoo’s poetry is an elegant yet powerful vindication of his communal

worldviews rooted in nomadism and in his poem “The ruins and reflection”

he also recurs to metamorphosis to conceptualise the steppe as a human

body, which serves as a metaphor to project the resilient ecology of the

steppes : Have you died? You seem like a dry sea / But you are the fleshing

steppe / From your peaceful eyes / I know you have already forgot / Kublai

Khan’s sadness / And Togoontumur Khan’s shame / You are only but sunk

in sleep on the land / Your hair is bits of tiles / Your body is rocks

/ You are the troubled sea.

This poem is a good example of how humans perceive the

world through the body used as a reference, like much cognitive theory

suggests today, and that landscapes embody emotions and memories derived

from personal and interpersonal experience.

As cultural geographer Christopher Tilley suggests, “Knowledge

and metaphorical understanding of landscape is intimately bound up with

the experience of the human body in place, and in movement between places.

The significance of places in the landscapes is continually being woven

into the fabric of social life, and anchored to the topographies of the

landscape”.

Thus, if we read this blend as the interrelation of the

sensuous ingredients of both body and the geography of the steppes, the

perceived effect is one of pleasurable affinity between humans and land,

but also resilience and strength. The separation between body and environment

seems to disappear as the distinction between body and land is difficult

to discern. In other words, self and environment merge into a hybrid entity

where body and environment are cognitively and sensuously connected.

To sum up, if the earth is conceived as tissue-clothing,

the earth is seen as a potentially flexible entity to which the indigenous

body is fully adapted because both the body and the earth are perceived

as having the same shape. If readers know that a nomadic way of life requires

a perceptual attuning to the shapes of the physical world, it is easier

for them to understand the conceptualisation of earth as a body. But there

is also another interesting aspect in the poem, the auditory space that

readers enter through the interpellatory “Have you died”, which is

used to address the steppe as a humanised entity. As readers enter this

space, they may wish to elaborate its acousticity, the sonority of the

poet’s voice addressing the steppes in the open air, its resonance in

the sky as the wind blows….

This poetic technique asserts Indigenous land as a unique

entity replete with cultural meaning, against marketing and commodifying

criteria that strips off its centuries old significance. Finally, with

the Indigenous poetry of Walissu Youkan we travel to the hunter-gatherer

territories of the Atayal tribe in Taiwan. The poet is a well-known poet,

teacher and activist who has devoted his entire life to the protection

of the Taiwanese Aborigines' lifestyle against mass assimilation, racism,

environmental destruction and the commodification of their culture as object

of ethnic tourism.

About Atayal

1. Birth Prayer / The baby is about to be born / Come

quickly, come, my child / Come out and meet us / Grandpa has a little tribal

dagger ready / Waiting for the first animal of your hunt / Grandma gets

her weaving machine ready / Waiting to make the first fine clothes for

you / Here it comes, here is the baby / A pair of eagle's eyes, flashing

/ Limbs strong as leopard's / A bear's heart, the voice of a waterfall

/ Fine-grass-hair, a mountain body / A perfect baby / From the bottom of

the mother's soul / Formed an Atayal (841-43).

In this powerful, epic poem, the features of the new-born

babe are called into existence by images drawn from a hunter's habitat.

Similes align the baby with natural landscape and wild animals to which

its future is tied. As seen in the previous poems, conceptual blending

can help us understand the profound interrelation between Indigenous individuals,

community and environment as the new-born baby acquires and the natural

elements become one indissoluble entity: The distinct identity construction

works by image-identifications with objects in the wilds, including landscape,

plants, and animals. Language and biodiversity are thus tied as the conceptual

blend projects a particular way of occupying, engaging with and shaping

the natural environment which will nurture the baby’s cultural, physical

and spiritual life.

Cognitive Mapping V: Ecopoetics as counter-hegemony

The cognitive mapping opens up a potential space of shared

consciousness where readers access the writer’s sense of dislocation

through the poems’ conceptual and sensory information. This space is

crucial for the readers’ realisation of potentially shared concerns and

struggles, and opens the space of the political. In this sense, the common

empowering discourse must be based on the writers’ shared concern with

the loss of cultural and biological biodiversity underlying the poems’

sentient imagery.

The conceptual and sensory information of the poems can

be seen as a link between nature and culture as the metaphors are expressive

of worldviews that emerge from constant dialogue with the environment.

The importance of the cognitive mapping lies thus in the fact that the

biological and cultural diversity underpinning the sentient metaphors increase

the resilience of natural and cultural systems which operate like an autopoietic

feedback loop. It is thus crucial to articulate the poems’ imagery as

part of a larger network of resistance against the loss of cultural and

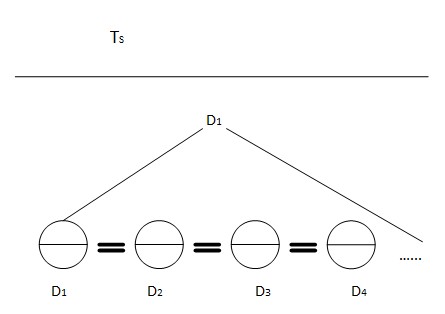

biological diversity. We could summarise Ernesto Laclau’s articulation

theory by representing the relation between local demand and global oppression

in a diagram where the oppressive form, whatever shape it takes, is separated

from the rest of society whereas the particular demands are represented

with a semi-circle that “makes their equivalential relation possible”

(Laclau, 2000: 304):

GC

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

D1

Ө ═ Ө

═ Ө ═ Ө ═

Ө ═ Ө ═ Ө

═ Ө ═ Ө

D1 D2

D3 D4

D5 D6

D7 D8

D9

In this diagram GC stands for the different manifestations

of global capitalism, separated from the rest of demands by a discontinuous

line as the interests of local demands and hegemonic power are not convergent

in a global-capitalist type of economy; however, the line is discontinuous

as local struggles are not immune to the effects of global capitalism.

The semi-circles D1…D9 for the particular demands, split between a bottom

semi-circle representing the particular Indigenous worldviews as seen in

the poems. The top semi-circle represents the common opposition to the

project of global capitalism. This leads to one of the particular demands

representing the whole chain as an empty signifier. For instance, the metaphors

of humanised nature seen in the three poems share an anti-system critique

against the commodification and exploitation of Indigenous land by corporate

capitalism.

Particularly, this anti-system critique appears as conceptual

and sensory information retrieved by readers during the reading process.

In other words, the readers’ journey through the textual

geographies enacts “dense interactions and emotional and affective

exchanges” that “are expressive of the continuing process of the formation

of collective identities” (Slater, 2004: 201) and contribute to the formation

of “[…] a counter -hegemonic globalisation from below that not only

challenges the neo-liberal doctrine of capitalist expansion and a resurgent

imperialism” (Slater, 2004: 221).

go back to Art

in

Society # 16 contents

|