No man is an island, no country, no artist of any place

in the world. And the events in Lebanon could not leave Saad el Girgawi

untouched. The form his commitment takes is quiet, and at the same

time disquieting. Death, even in its more massive, multiplied form, even

in genocide, comes always to concrete human beings. Each one of them suffers;

his or her own pain, in that sense, is always unique. But death, in some

historical situations, is also typical, a shared or collective experience.

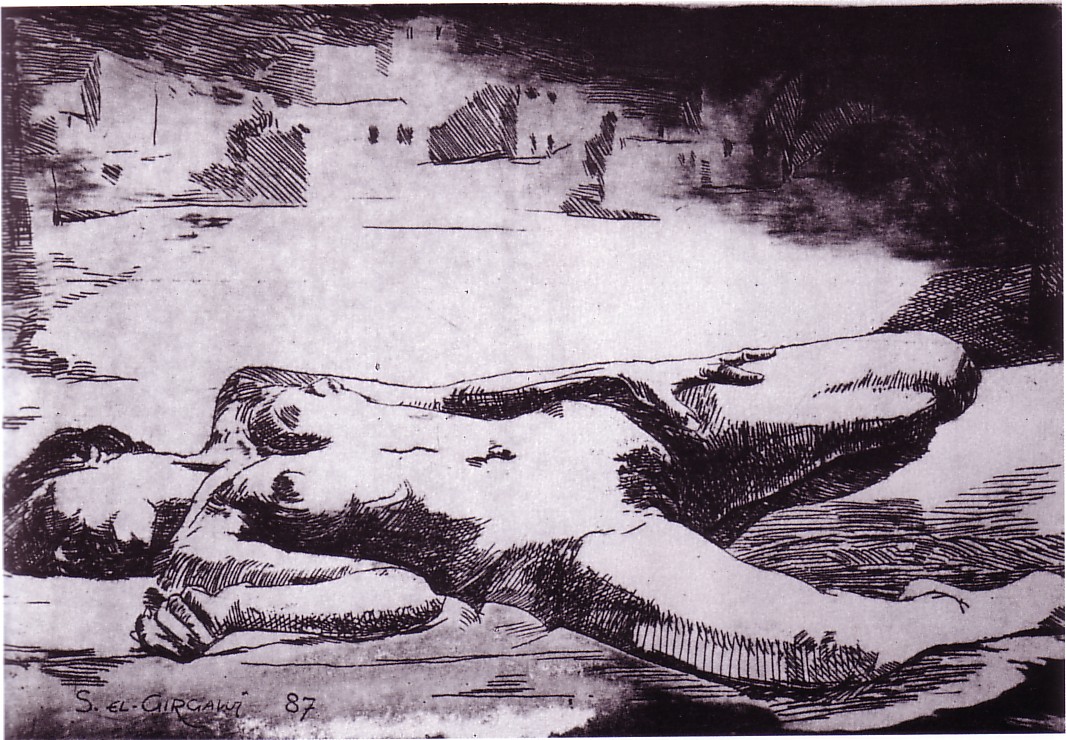

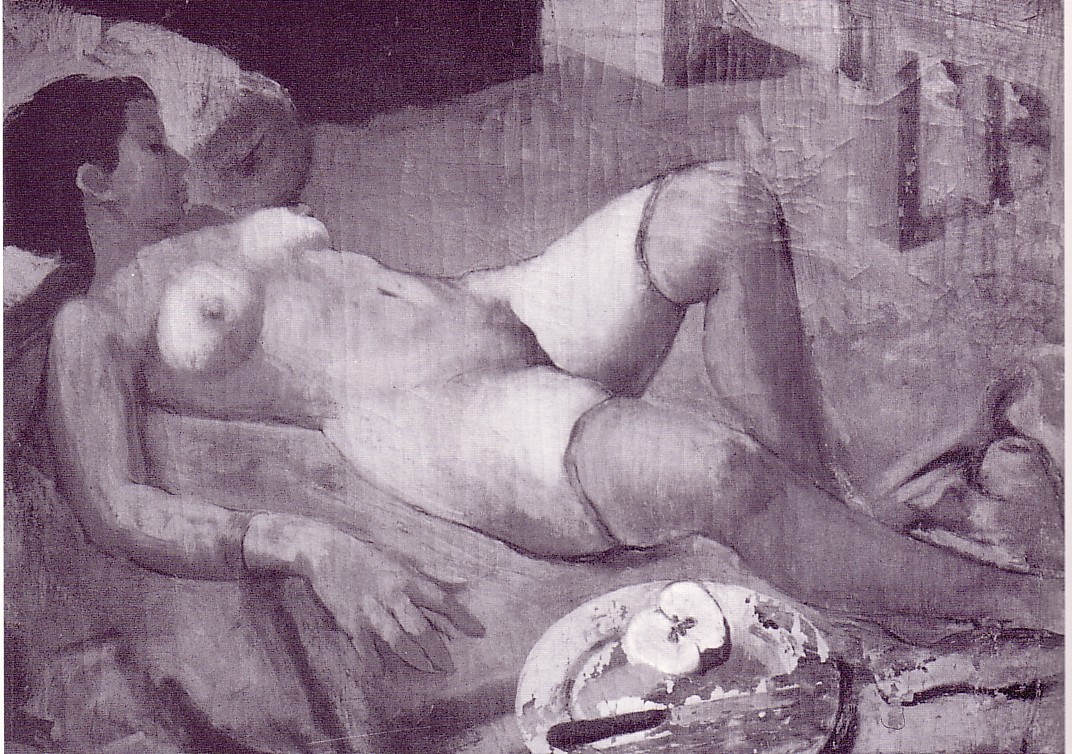

In Saad’s work, The Dead One of Beirut , both the typical and the

individual are present; they converge in the same dead body in the foreground

of this lithography. The body is that of a nude young girl, or young woman

on an empty square. Stretched out, she is lying there, in – is it the sun,

or the moonlight? As if having given herself to a lover, tired, exhausted,

she rest there, in front of the invading darkness.

Her body raped, her lean arm still on her thigh, the

other as if grasping an amulet, she is separated from the distant houses,

a modern Antigone sacrificed by the civil war, a war instigated by the

rich of the city, those allied to outsiders, a bridgehead of globalization,

a class living on another planet, in another world.

This small lithography, done in 1987, gives a mute

answer to the events that devastated Beirut, an answer that is also a question,

asking us to look for, and identify the social forces responsible

for its suffering, its undoing.

Antigone was thrown to the wolves outside the town walls,

and so is this body, thrown to the voyeurs, a really disconcerting aspect

of this work. Silently, a pray for those without pity, she lies there on

the pavement as we stare at her. While the others, surviving victims as

well as perpetrators of such cruelty, know all to well how to remain

invisible.

The J’accuse inscribed in this lithography cannot

be overlooked. The human shape, its suffering at the moment of death

seem universal. But the context is specific, and so is the formal approach

of this work. The wood-cuts done by Chinese artists denouncing cruelties

committed by Kuomintang forces during the civil war ending in 1949

have their own strength and cannot be compared to Saad’s work; neither

can the works of Kaethe Kollwitz that opposed the insanity of imperialist

war. In The Dead One of Beirut, the strength of the composition

depends on the preponderance of horizontal lines and basically horizontal

shapes: The outlines of the square, and of the Arab houses, made

of clay bricks, with their emphasis on the horizontal, underscore the tiredness,

the suffering, the final breath of this outstretched, naked body, so close

to the earth. As a lifeless body she is married to the earth, but also

standing out from it: From her left shoulder to her left knee we see almost

a long straight line, and this while the left knee is slightly raised,

the leg bending, with the left foot disappearing under the buttocks… Saad

himself has observed once that “perpendicularity,” a preponderance of horizontal

and vertical lines, is characteristic of much of his work, and that he

owes it to his perception of the Egyptian landscape, its trees and horizons,

but also its architecture. This may well be true. At least the works rings

with a special quality that may well be derived from the socio-culture

it was fed by and responded to.

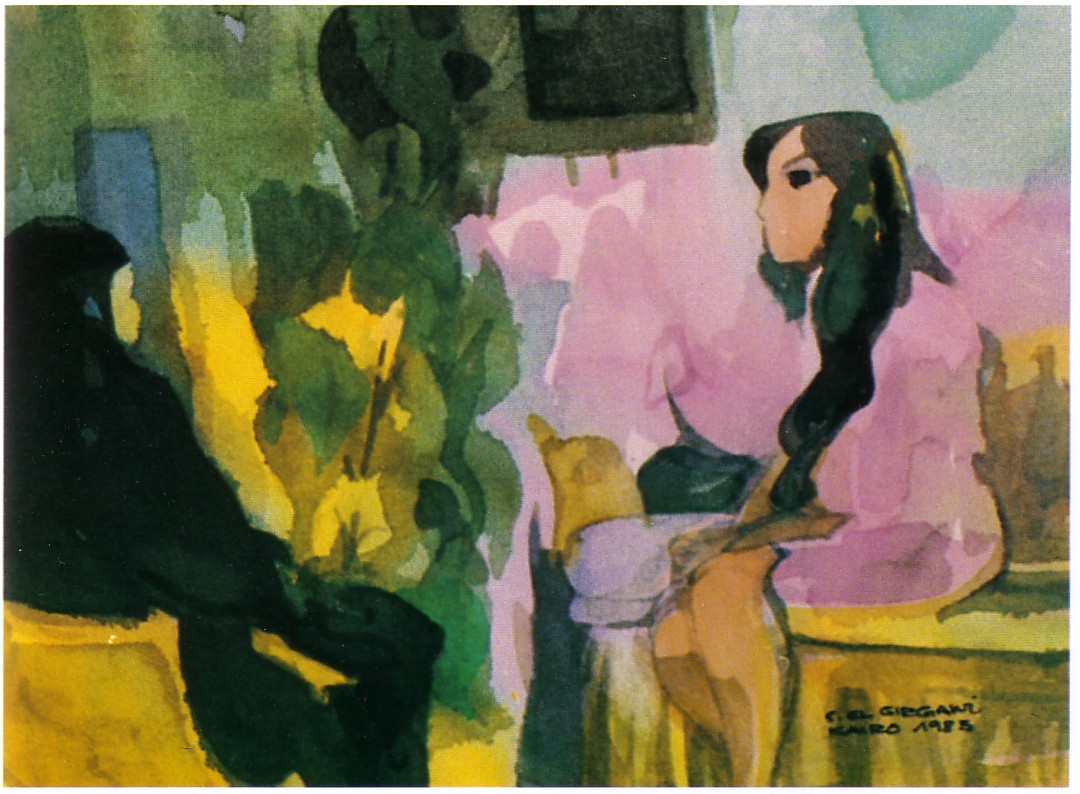

Like other works of Saad, the one called Women Carrying

A Heavy Load in a Cairo Alley (done in 1983) has no need of a central

perspective.

In fact is characterized by a multiple perspective (something

we might call, perhaps, “poly-perspectivistic”), the eyes of

the observer finding two focal points, one letting us intrude deeply into

the passageway on the left; the other sucking our eyes’ glance into the

dark hollow of a door scarcely visible on the right.

The scene shown in the painting is accentuated by a more

or less vertical rhythm of dark strokes of color, with few counterbalancing,

shorter, horizontal strokes, none of them quite as dark. |

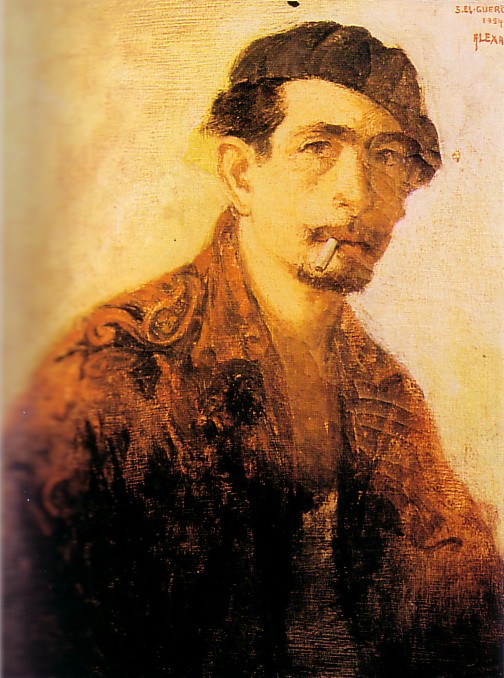

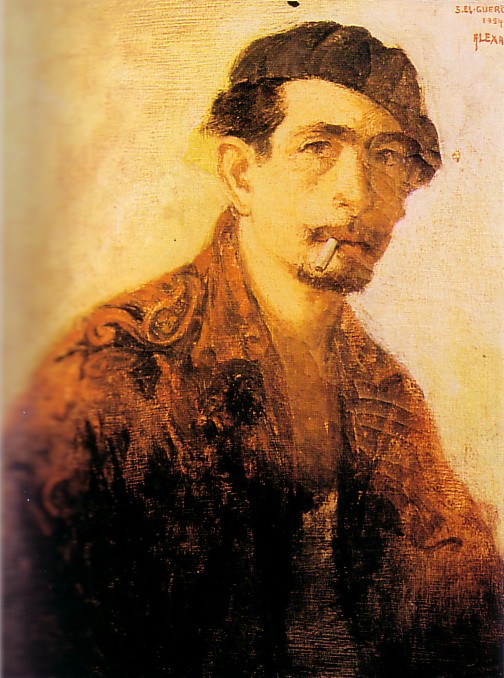

Self-Portrait,

Alexandria 1954 (oil on canvas)

Self-Portrait,

Alexandria 1954 (oil on canvas)

Self-Portrait,

Alexandria 1954 (oil on canvas)

Self-Portrait,

Alexandria 1954 (oil on canvas)